The Kaiserchronik (Imperial Chronicle) is a 12th-century chronicle written in 17,283 lines of Middle High German verse. [1] [2] It runs from Julius Caesar to Conrad III, and seeks to give a complete account of the history of Roman and German emperors and kings, based on a historiographical view of the continuity of the Roman and German successions. The overall pattern is of a progression from pagan to Christian worlds, and theological disputations stand at the turning-points of the Christianization of the Empire. [3] However, much of the material is legendary and fantastic, suggesting that large sections are compiled from earlier works, mostly shorter biographies and saints' lives. [4]

Contents

The chronicle was written in Regensburg some time after 1146. The poet (or at least the final compiler) was presumably a cleric in secular service, a partisan of the Guelphs. However the view that it was written by Konrad der Pfaffe, author of the Rolandslied , has been discredited. Known sources include the Chronicon Wirzeburgense , the Chronicle of Ekkehard of Aura, and the Annolied ; the relationship to the Annolied has received particular attention in scholarship, as earlier views of the priority of the Kaiserchronik, or of a shared source, were gradually dismissed. [5] Judging from the large number of surviving manuscripts (twelve complete and seventeen partial), it must have been very popular, and it was twice continued in the 13th century: the first addition, the "Bavarian continuation", comprised 800 verses, while the second, the "Swabian continuation", which brought the poem to the Interregnum (1254–73), consisted of 483 lines. The Kaiserchronik in turn was used as an important source for other verse chronicles in the thirteenth century, most notably that of Jans der Enikel.

The text of the Kaiserchronik is preserved in a total of some 50 manuscripts, of which 20 have the full text. Of these, five predate the 14th century, including one of the late 12th century (the Vorau ms.). [6] The main witnesses are:

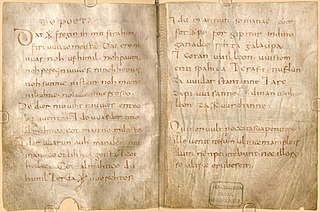

- Vorau, Stiftsbibl., Cod. 276 (früher XI), c. 1175-1200 (Schröder ms. 1)

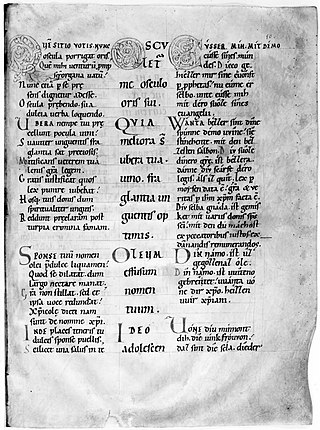

- Heidelberg, Universitätsbibl., Cpg 361, mid-13th c. (Schröder ms. 4)

- Prag, Nationalbibl., Cod. XXIII.G.43, c. 1225-1250 (Schröder ms. 18)

- Wien, Österr. Nationalbibl., Cod. 413, mid-13th c. (Schröder ms. 25)

- Wien, Österr. Nationalbibl., Cod. 2693, c. 1275-1300 (Schröder ms. 16)

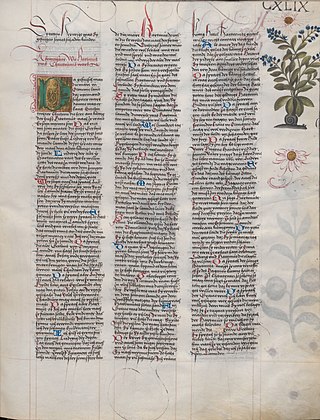

- München, Staatsbibl., Cgm 37, c. 1325-1350 (Schröder ms. 2)

- Wolfenbüttel, Herzog August Bibl., Cod. 15.2 Aug. 2°, early 14th c. (incomplete text, Schröder ms. 3)

The chronicle was first edited in full in 1849-54 by Hans Ferdinand Massmann. [7] Massmann was in a bitter academic dispute with August Heinrich Hoffmann von Fallersleben, an "almost proprietal struggle" over the priority of the respective manuscripts they had access to. Müller (1999) categorizes Massmann's work as an editionsphilologischer Amoklauf (as it were "editorial philology gone postal"), as Massmann goes out of his way to ignore the Vorau ms., to the point of using the 1639 edition of Annolied by Martin Opitz as a "Kaiserchronik fragment" in higher standing than the Vorau ms. [8] The only critical edition besides Massmann's is that of Edward Schröder (1892). [9] There is also a classroom edition of excerpts with parallel translations in English. [10]