The early details of the history of the Faroe Islands are unclear. It is possible that Brendan, an Irish monk, sailed past the islands during his North Atlantic voyage in the 6th century. He saw an 'Island of Sheep' and a 'Paradise of Birds', which some say could be the Faroes with its dense bird population and sheep. This does suggest however that other sailors had got there before him, to bring the sheep. Norsemen settled the Faroe Islands in the 9th or 10th century. The islands were officially converted to Christianity around the year 1000, and became a part of the Kingdom of Norway in 1035. Norwegian rule on the islands continued until 1380, when the islands became part of the dual Denmark–Norway kingdom, under king Olaf II of Denmark.

Old Norse, Old Nordic, or Old Scandinavian is a stage of development of North Germanic dialects before their final divergence into separate Nordic languages. Old Norse was spoken by inhabitants of Scandinavia and their overseas settlements and chronologically coincides with the Viking Age, the Christianization of Scandinavia and the consolidation of Scandinavian kingdoms from about the 8th to the 15th centuries.

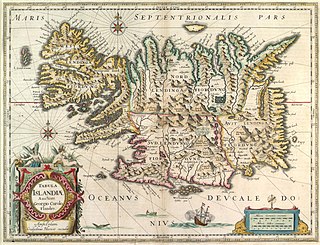

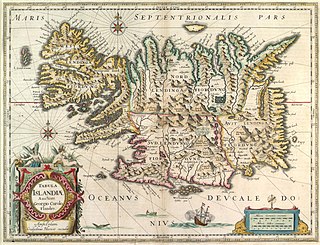

The recorded history of Iceland began with the settlement by Viking explorers and the people they enslaved from Western Europe, particularly in modern-day Norway and the British Isles, in the late ninth century. Iceland was still uninhabited long after the rest of Western Europe had been settled. Recorded settlement has conventionally been dated back to 874, although archaeological evidence indicates Gaelic monks from Ireland, known as papar according to sagas, may have settled Iceland earlier.

The Battle of Svolder was a large naval battle during the Viking age, fought in September 999 or 1000 in the western Baltic Sea between King Olaf of Norway and an alliance of the Kings of Denmark and Sweden and Olaf's enemies in Norway. The backdrop of the battle was the unification of Norway into a single independent state after longstanding Danish efforts to control the country, combined with the spread of Christianity in Scandinavia.

Garðaríki or Garðaveldi was the Old Norse term used in the Middle Ages for the lands of Rus'. According to Göngu-Hrólfs saga, the name Hólmgarðaríki was synonymous with Garðaríki, and these names were used interchangeably in several other Old Norse stories.

The Battle of Brávellir or the Battle of Bråvalla was a legendary battle, said to have taken place c. 770, that is described in the sagas as taking place on the Brávellir between Sigurd Hring, king of Sweden and the Geats of Västergötland, and his uncle Harald Wartooth, king of Denmark and the Geats of Östergötland.

The Gutes were a North Germanic tribe inhabiting the island of Gotland. The ethnonym is related to that of the Goths (Gutans), and both names were originally Proto-Germanic *Gutaniz. Their language is called Gutnish (gutniska). They are one of the progenitor groups of modern Swedes, along with historical Swedes and Geats.

Hrafnkels saga or Hrafnkels saga Freysgoða is one of the Icelanders' sagas. It tells of struggles between chieftains and farmers in the east of Iceland in the 10th century. The eponymous main character, Hrafnkell, starts out his career as a fearsome duelist and a dedicated worshiper of the god Freyr. After suffering defeat, humiliation, and the destruction of his temple, he becomes an atheist. His character changes and he becomes more peaceful in dealing with others. After gradually rebuilding his power base for several years, he achieves revenge against his enemies and lives out the rest of his life as a powerful and respected chieftain. The saga has been interpreted as the story of a man who arrives at the conclusion that the true basis of power does not lie in the favor of the gods but in the loyalty of one's subordinates.

Gutasaga (Gutasagan) is a saga regarding the history of Gotland before its Christianization. It was recorded in the 13th century and survives in only a single manuscript, the Codex Holm. B 64, dating to c. 1350, kept at the National Library of Sweden in Stockholm together with the Gutalag, the legal code of Gotland. It was written in the Old Gutnish language, a variety of Old Norse.

Old Swedish is the name for two distinct stages of the Swedish language that were spoken in the Middle Ages: Early Old Swedish, spoken from about 1225 until about 1375, and Late Old Swedish, spoken from about 1375 until about 1526.

Ásatrúarfélagið, also known simply as Ásatrú, is an Icelandic religious organisation of heathenry. It was founded on the first day of summer in 1972, and granted recognition as a registered religious organization in 1973, allowing it to conduct legally binding ceremonies and collect a share of the church tax. The Allsherjargoði is the chief religious official.

The Ingvar runestones is the name of around 26 Varangian Runestones that were raised in commemoration of those who died in the Swedish Viking expedition to the Caspian Sea of Ingvar the Far-Travelled.

The Greece runestones are about 30 runestones containing information related to voyages made by Norsemen to the Byzantine Empire. They were made during the Viking Age until about 1100 and were engraved in the Old Norse language with Scandinavian runes. All the stones have been found in modern-day Sweden, the majority in Uppland and Södermanland. Most were inscribed in memory of members of the Varangian Guard who never returned home, but a few inscriptions mention men who returned with wealth, and a boulder in Ed was engraved on the orders of a former officer of the Guard.

The England runestones are a group of about 30 runestones in Scandinavia which refer to Viking Age voyages to England. They constitute one of the largest groups of runestones that mention voyages to other countries, and they are comparable in number only to the approximately 30 Greece Runestones and the 26 Ingvar Runestones, of which the latter refer to a Viking expedition to the Caspian Sea region. They were engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark.

The Varangian Runestones are runestones in Scandinavia that mention voyages to the East or the Eastern route, or to more specific eastern locations such as Garðaríki in Eastern Europe.

The Viking runestones are runestones that mention Scandinavians who participated in Viking expeditions. This article treats the runestone that refer to people who took part in voyages abroad, in western Europe, and stones that mention men who were Viking warriors and/or died while travelling in the West. However, it is likely that all of them do not mention men who took part in pillaging. The inscriptions were all engraved in Old Norse with the Younger Futhark. The runestones are unevenly distributed in Scandinavia: Denmark has 250 runestones, Norway has 50 while Iceland has none. Sweden has as many as between 1,700 and 2,500 depending on definition. The Swedish district of Uppland has the highest concentration with as many as 1,196 inscriptions in stone, whereas Södermanland is second with 391.

The Baltic area runestones are Viking runestones in memory of men who took part in peaceful or warlike expeditions across the Baltic Sea, where Finland and the Baltic states are presently located.

This is a timeline of Icelandic history, comprising important legal and territorial changes and political events in Iceland and its predecessor states. To read about the background to these events, see history of Iceland.

The Faroese sheep is a breed of sheep native to the Faroe Islands.

The term "halberd" has been used to translate several Old Norse words relating to polearms in the context of Viking Age arms and armour, and in scientific literature about the Viking Age. In referring to the Viking Age weapon, the term "halberd" is not to be taken as referring to the classical Swiss halberd of the 15th century, but rather in its literal sense of "axe-on-a-pole", describing a weapon of the more general glaive type.