Middle Dutch is a collective name for a number of closely related West Germanic dialects whose ancestor was Old Dutch. It was spoken and written between 1150 and 1500. Until the advent of Modern Dutch after 1500 or c. 1550, there was no overarching standard language, but all dialects were mutually intelligible. During that period, a rich Medieval Dutch literature developed, which had not yet existed during Old Dutch. The various literary works of the time are often very readable for speakers of Modern Dutch since Dutch is a rather conservative language.

The voiced bilabial fricative is a type of consonantal sound, used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨β⟩, and the equivalent X-SAMPA symbol is B. The official symbol ⟨β⟩ is the Greek letter beta.

The voiceless uvular fricative is a type of consonantal sound that is used in some spoken languages. The symbol in the International Phonetic Alphabet that represents this sound is ⟨χ⟩, the Greek chi. The sound is represented by ⟨x̣⟩ in Americanist phonetic notation. It is sometimes transcribed with ⟨x⟩ in broad transcription.

Limburgish, also called Limburgan, Limburgian, or Limburgic, is a West Germanic language spoken in the Dutch and Belgian provinces of Limburg and in the neighbouring regions of Germany.

The Nuer language (Thok Naath) ("people's language") is a Nilotic language of the Western Nilotic group. It is spoken by the Nuer people of South Sudan and in western Ethiopia (region of Gambela). The language is very similar to Dinka and Atuot.

The sound system of Norwegian resembles that of Swedish. There is considerable variation among the dialects, and all pronunciations are considered by official policy to be equally correct – there is no official spoken standard, although it can be said that Eastern Norwegian Bokmål speech has an unofficial spoken standard, called Urban East Norwegian or Standard East Norwegian, loosely based on the speech of the literate classes of the Oslo area. This variant is the most common one taught to foreign students.

The phonology of the Persian language varies between regional dialects, standard varieties, and even from older variates of Persian. Persian is a pluricentric language and countries that have Persian as an official language have separate standard varieties, namely: Standard Dari (Afghanistan), Standard Iranian Persian and Standard Tajik (Tajikistan). The most significant differences between standard varieties of Persian are their vowel systems. Standard varieties of Persian have anywhere from 6 to 8 vowel distinctions, and similar vowels may be pronounced differently between standards. However, there are not many notable differences when comparing consonants, as all standard varieties a similar amount of consonant sounds. Though, colloquial varieties generally have more differences than their standard counterparts. Most dialects feature contrastive stress and syllable-final consonant clusters.

Dutch phonology is similar to that of other West Germanic languages, especially Afrikaans and West Frisian.

Central or Middle Franconian refers to the following continuum of West Central German dialects:

The Rheinische Dokumenta is a phonetic writing system developed in the early 1980s by a working group of academics, linguists, local language experts, and local language speakers of the Rhineland. It was presented to the public in 1986 by the Landschaftsverband Rheinland.

Hard and soft G in Dutch refers to a phonetic phenomenon of the pronunciation of the letters ⟨g⟩ and ⟨ch⟩ and also a major isogloss within that language.

This article covers the phonology of modern Colognian as spoken in the city of Cologne. Varieties spoken outside of Cologne are only briefly covered where appropriate. Historic precedent versions are not considered.

The Sittard dialect is a Limburgish dialect spoken mainly in the Dutch city of Sittard. It is also spoken in Koningsbosch and in a small part of Germany (Selfkant), but quickly becoming extinct there. Of all other important Limburgish dialects, the dialect of Sittard is most closely related to that of Roermond.

This article aims to describe the phonology and phonetics of central Luxembourgish, which is regarded as the emerging standard.

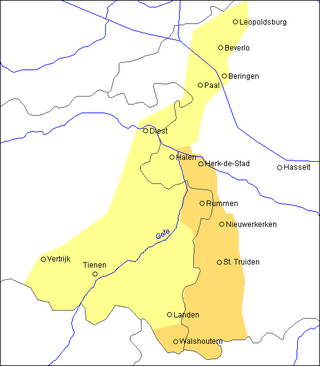

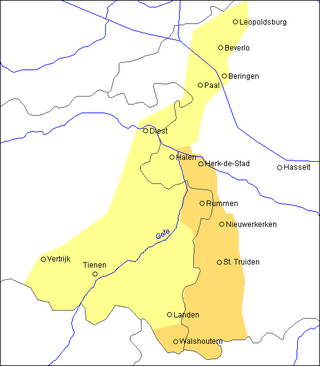

This article covers the phonology of the Orsmaal-Gussenhoven dialect, a variety of Getelands spoken in Orsmaal-Gussenhoven, a village in the Linter municipality.

Hamont-Achel dialect or Hamont-Achel Limburgish is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Belgian city of Hamont-Achel alongside the Dutch language.

Kerkrade dialect is a Ripuarian dialect spoken in Kerkrade and its surroundings, including Herzogenrath in Germany. It is spoken in all social classes, but the variety spoken by younger people in Kerkrade is somewhat closer to Standard Dutch.

Weert dialect or Weert Limburgish is the city dialect and variant of Limburgish spoken in the Dutch city of Weert alongside Standard language. All of its speakers are bilingual with standard Dutch. There are two varieties of the dialect: rural and urban. The latter is called Stadsweerts in Standard Dutch and Stadswieërts in the city dialect. Van der Looij gives the Dutch name buitenijen for the peripheral dialect.

This article covers the phonology of the Kerkrade dialect, a West Ripuarian language variety spoken in parts of the Kerkrade municipality in the Netherlands and Herzogenrath in Germany.

Getelands or West Getelands is a South Brabantian dialect spoken in the eastern part of Flemish Brabant as well as the western part of Limburg in Belgium. It is a transitional dialect between South Brabantian and West Limburgish.