The Battle of Waterloo was fought on Sunday 18 June 1815, near Waterloo, marking the end of the Napoleonic Wars. A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by two armies of the Seventh Coalition. One of these was a British-led force with units from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Hanover, Brunswick, and Nassau, under the command of the Duke of Wellington. The other comprised three corps of the Prussian army under Field Marshal Blücher; a fourth corps of this army fought at the Battle of Wavre on the same day. The battle was known contemporarily as the Battle of Mont Saint-Jean in France and La Belle Alliance in Prussia.

Combined arms is an approach to warfare that seeks to integrate different combat arms of a military to achieve mutually complementary effects—for example, using infantry and armour in an urban environment in which each supports the other.

Major-General Sir William Ponsonby was an Anglo-Irish politician and British Army officer who served in the Peninsular War and was killed at the Battle of Waterloo.

La Grande Armée was the main military component of the French Imperial Army commanded by Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte during the Napoleonic Wars. From 1804 to 1808, it won a series of military victories that allowed the French Empire to exercise unprecedented control over most of Europe. Widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest fighting forces ever assembled, it suffered enormous losses during the disastrous Peninsular War followed by the invasion of Russia in 1812, after which it never recovered its strategic superiority and ended in total defeat for Napoleonic France by the Peace of Paris in 1815.

Cuirassiers were cavalry equipped with a cuirass, sword, and pistols. Cuirassiers first appeared in mid-to-late 16th century Europe as a result of armoured cavalry, such as men-at-arms and demi-lancers discarding their lances and adopting pistols as their primary weapon. In the later part of the 17th century, the cuirassier lost his limb armour and subsequently wore only the cuirass, and sometimes a helmet. By this time, the sword or sabre had become his primary weapon, with pistols relegated to a secondary function.

Uhlans were a type of light cavalry, primarily armed with a lance. They first appeared in the cavalry of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, in the early 18th century. Uhlans were quickly adopted by the mounted forces of other countries, including France, Russia, Prussia, Saxony, and Austria-Hungary. The term "lancer" was often used interchangeably with "uhlan"; the lancer regiments later formed for the British Army were directly inspired by the uhlans of other armies.

Horse artillery was a type of light, fast-moving, and fast-firing artillery which provided highly mobile fire support, especially to cavalry units. Horse artillery units existed in armies in Europe, the Americas, and Asia, from the early 17th to the mid-20th century. A precursor of modern self-propelled artillery, it consisted of light cannons or howitzers attached to light but sturdy two-wheeled carriages called caissons or limbers, with the individual crewmen riding on horses. This was in contrast to the rest of the field artillery, which were also horse-drawn but whose gunners were normally transported seated on the gun carriage, wagons or limbers.

The Coalition forces of the Napoleonic Wars were composed of Napoleon Bonaparte's enemies: the United Kingdom, the Austrian Empire, Kingdom of Prussia, Kingdom of Spain, Kingdom of Naples, Kingdom of Sicily, Kingdom of Sardinia, Dutch Republic, Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, Kingdom of Portugal, Kingdom of Sweden, and various German and Italian states at differing times in the wars. At their height, the Coalition could field formidable combined forces of about 1,740,000 strong. This outnumbered the 1.1 million French soldiers. The breakdown of the more active armies are: Austria, 570,000; Britain, 250,000; Prussia, 300,000; and Russia, 600,000.

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine pulling wagons. By 1600 BC, improved harness and chariot designs made chariot warfare common throughout the Ancient Near East, and the earliest written training manual for war horses was a guide for training chariot horses written about 1350 BC. As formal cavalry tactics replaced the chariot, so did new training methods, and by 360 BC, the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon had written an extensive treatise on horsemanship. The effectiveness of horses in battle was also revolutionized by improvements in technology, such as the invention of the saddle, the stirrup, and the horse collar.

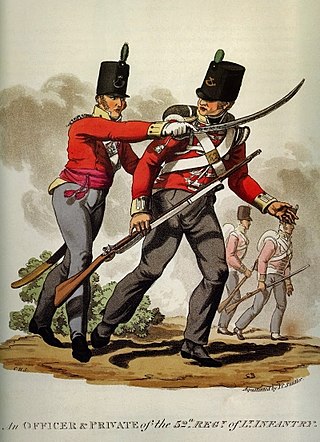

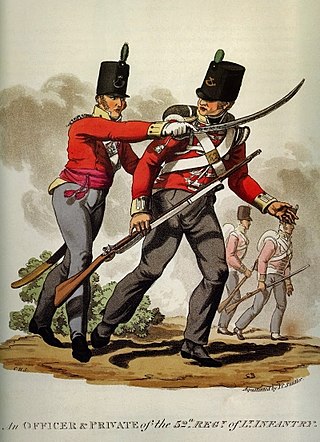

The 52nd (Oxfordshire) Regiment of Foot was a light infantry regiment of the British Army throughout much of the 18th and 19th centuries. The regiment first saw active service during the American War of Independence, and were posted to India during the Anglo-Mysore Wars. During the Napoleonic Wars, the 52nd were part of the Light Division, and were present at most major battles of the Peninsula campaign, becoming one of the most celebrated regiments, described by Sir William Napier as "a regiment never surpassed in arms since arms were first borne by men". They had the largest British battalion at Waterloo, 1815, where they formed part of the final charge against Napoleon's Imperial Guard. They were also involved in various campaigns in India.

The 4th Cavalry Brigade was a cavalry brigade of the British Army. It served in the Napoleonic Wars, in the First World War on the Western Front where it was initially assigned to The Cavalry Division before spending most of the war with the 2nd Cavalry Division, and with the 1st Cavalry Division during the Second World War.

The British Army during the Napoleonic Wars experienced a time of rapid change. At the beginning of the French Revolutionary Wars in 1793, the army was a small, awkwardly administered force of barely 40,000 men. By the end of the period, the numbers had vastly increased. At its peak, in 1813, the regular army contained over 250,000 men. The British infantry was "the only military force not to suffer a major reverse at the hands of Napoleonic France."

The types of military forces in the Napoleonic Wars represented the unique tactical use of distinct military units, or their origin within different European regions. By and large the military forces during the period had not changed significantly from those of the 18th century, although their employment would differ significantly.

Alexander Cavalié Mercer was a British artillery officer. Although he rose to the rank of general, his fame is as commander of G Troop Royal Horse Artillery in the thick of the fighting at the Battle of Waterloo, and as author of Journal of the Waterloo Campaign.

Napoleonic tactics describe certain battlefield principles used by national armies from the late 18th century until the invention and adoption of the rifled musket in the mid 19th century. Napoleonic tactics are characterised by intense drilling of soldiers; speedy battlefield movement; combined arms assaults between infantry, cavalry, and artillery; relatively small numbers of cannon; short-range musket fire; and bayonet charges. French Emperor Napoleon I is considered by military historians to have been a master of this particular form of warfare. Military powers would continue to employ such tactics even as technological advancements during the industrial revolutions gradually rendered them impractically obsolete, leading to devastating losses of life in the American Civil War, the Franco-Prussian War, and the World War I.

In the Battle of Campo Maior, or Campo Mayor, on 25 March 1811, Brigadier General Robert Ballard Long with a force of Anglo-Portuguese cavalry, the advance-guard of the army commanded by William Beresford, clashed with a French force commanded by General of Division Marie Victor de Fay, marquis de Latour-Maubourg. Initially successful, some of the Allied horsemen indulged in a reckless pursuit of the French. An erroneous report was given that they had been captured wholesale. In consequence, Beresford halted his forces and the French were able to escape and recover a convoy of artillery pieces.

The 1st Cavalry Brigade was a brigade of the British Army. It served in the Napoleonic Wars, the Anglo-Egyptian War, the Boer War and in the First World War when it was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division.

The 2nd Cavalry Brigade was a brigade of the British Army. It served in the Napoleonic Wars, the Boer War and in the First World War when it was assigned to the 1st Cavalry Division.

The 7th Cavalry Brigade was a cavalry brigade of the British Army. It served in the Napoleonic Wars, notably at the Battle of Waterloo. It was reformed in 1914 and served on the Western Front as part of the 3rd Cavalry Division until the end of World War I.

The French Imperial Army was the land force branch of the French imperial military during the Napoleonic era.