Historically, cavalry are soldiers or warriors who fight mounted on horseback. Cavalry were the most mobile of the combat arms, operating as light cavalry in the roles of reconnaissance, screening, and skirmishing in many armies, or as heavy cavalry for decisive shock attacks in other armies. An individual soldier in the cavalry is known by a number of designations depending on era and tactics, such as a cavalryman, horseman, trooper, cataphract, knight, drabant, hussar, uhlan, mamluk, cuirassier, lancer, dragoon, or horse archer. The designation of cavalry was not usually given to any military forces that used other animals for mounts, such as camels or elephants. Infantry who moved on horseback, but dismounted to fight on foot, were known in the early 17th to the early 18th century as dragoons, a class of mounted infantry which in most armies later evolved into standard cavalry while retaining their historic designation.

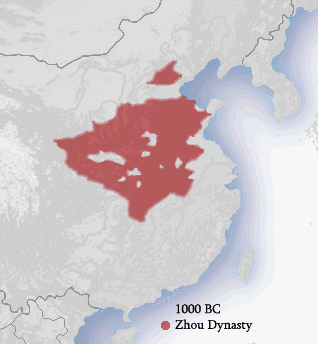

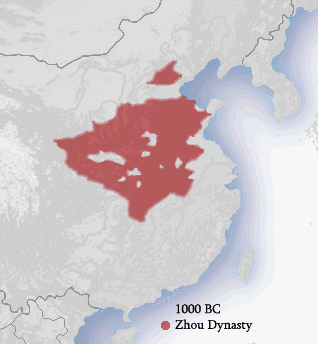

The Zhou dynasty was a royal dynasty of China that followed the Shang dynasty. Having lasted 789 years, the Zhou dynasty was the longest dynastic regime in Chinese history. The military control of ancient China by the royal house, surnamed Ji, lasted from 1046 until 771 BC for a period known as the Western Zhou, and the political sphere of influence it created continued well into the Eastern Zhou period for another 500 years. The establishment date of 1046 BC is supported by the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project and David Pankenier, but David Nivison and Edward L. Shaughnessy date the establishment to 1045 BC.

A cataphract was a form of armored heavy cavalry that originated in Persia and was fielded in ancient warfare throughout Eurasia and Northern Africa.

A stirrup is a light frame or ring that holds the foot of a rider, attached to the saddle by a strap, often called a stirrup leather. Stirrups are usually paired and are used to aid in mounting and as a support while using a riding animal. They greatly increase the rider's ability to stay in the saddle and control the mount, increasing the animal's usefulness to humans in areas such as communication, transportation, and warfare.

The recorded military history of China extends from about 2200 BC to the present day. Chinese pioneered the use of crossbows, advanced metallurgical standardization for arms and armor, early gunpowder weapons, and other advanced weapons, but also adopted nomadic cavalry and Western military technology. China's armies also benefited from an advanced logistics system as well as a rich strategic tradition, beginning with Sun Tzu's The Art of War, that deeply influenced military thought.

Ancient warfare is war that was conducted from the beginning of recorded history to the end of the ancient period. The difference between prehistoric and ancient warfare is more organization oriented than technology oriented. The development of first city-states, and then empires, allowed warfare to change dramatically. Beginning in Mesopotamia, states produced sufficient agricultural surplus. This allowed full-time ruling elites and military commanders to emerge. While the bulk of military forces were still farmers, the society could portion off each year. Thus, organized armies developed for the first time. These new armies were able to help states grow in size and become increasingly centralized.

Mounted infantry were infantry who rode horses instead of marching. The original dragoons were essentially mounted infantry. According to the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica, "Mounted rifles are half cavalry, mounted infantry merely specially mobile infantry." Today, with motor vehicles having replaced horses for military transport, the motorized infantry are in some respects successors to mounted infantry.

Chinese armour was predominantly lamellar from the Warring States period onward, prior to which animal parts such as rhinoceros hide, rawhide, and turtle shells were used for protection. Lamellar armour was supplemented by scale armour since the Warring States period or earlier. Partial plate armour was popular from the Eastern and Southern dynasties (420–589), and mail and mountain pattern armour from the Tang dynasty (618–907). Chain mail had been known since the Han dynasty, but did not see widespread production or battlefield use, and may have seen as "exotic foreign armor" used as a display of wealth for wealthier officers and soldiers. During the Ming dynasty (1368–1644), brigandine began to supplant lamellar armour and was used to a great degree into the Qing dynasty (1644–1912). By the 19th century most Qing armour, which was of the brigandine type, were purely ceremonial, having kept the outer studs for aesthetic purposes, and omitted the protective metal plates.

The Eurasian nomads were groups of nomadic peoples living throughout the Eurasian Steppe, who are largely known from frontier historical sources from Europe and Asia.

The Han–Xiongnu War, also known as the Sino–Xiongnu War, was a series of military conflicts fought over two centuries between the Chinese Han Empire and the nomadic Xiongnu confederation, although extended conflicts can be traced back as early as 200 BC and ahead as late as 188 AD.

The first evidence of horses in warfare dates from Eurasia between 4000 and 3000 BC. A Sumerian illustration of warfare from 2500 BC depicts some type of equine pulling wagons. By 1600 BC, improved harness and chariot designs made chariot warfare common throughout the Ancient Near East, and the earliest written training manual for war horses was a guide for training chariot horses written about 1350 BC. As formal cavalry tactics replaced the chariot, so did new training methods, and by 360 BC, the Greek cavalry officer Xenophon had written an extensive treatise on horsemanship. The effectiveness of horses in battle was also revolutionized by improvements in technology, such as the invention of the saddle, the stirrup, and the horse collar.

The Ordos culture was a material culture occupying a region centered on the Ordos Loop during the Bronze and early Iron Age from c. 800 BCE to 150 BCE. The Ordos culture is known for significant finds of Scythian art and may represent the easternmost extension of Indo-European Eurasian nomads, such as the Saka, or may be linkable to Palaeo-Siberians or Yeniseians. Under the Qin and Han dynasties, the area came under the control of contemporaneous Chinese states.

Nomadic empires, sometimes also called steppe empires, Central or Inner Asian empires, were the empires erected by the bow-wielding, horse-riding, nomadic people in the Eurasian Steppe, from classical antiquity (Scythia) to the early modern era (Dzungars). They are the most prominent example of non-sedentary polities.

Ferghana horses were one of China's earliest major imports, originating in an area in Central Asia. These horses, as depicted in Tang dynasty tomb figures in earthenware, may "resemble the animals on the golden medal of Eucratides, King of Bactria ."

Mounted archery is a form of archery that involves shooting arrows while on horseback. A horse archer is a person who does mounted archery. Archery has occasionally been used from the backs of other riding animals. In large open areas, mounted archery was a highly successful technique for hunting, for protecting herds, and for war. It was a defining characteristic of the Eurasian nomads during antiquity and the medieval period, as well as the Iranian peoples such as the Alans, Sarmatians, Cimmerians, Scythians, Massagetae, Parthians, and Persians in Antiquity, and by the Hungarians, Mongols, Chinese, and Turkic peoples during the Middle Ages. The expansion of these cultures have had a great influence on other geographical regions including Eastern Europe, West Asia, and East Asia. In East Asia, horse archery came to be particularly honored in the samurai tradition of Japan, where horse archery is called Yabusame.

Horses in East Asian warfare are inextricably linked with the strategic and tactical evolution of armed conflict throughout the course of East Asian military history. A warrior on horseback or horse-drawn chariot changed the balance of power between the warring civilizations throughout the arc of East Asian military history.

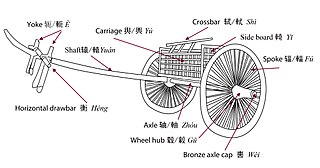

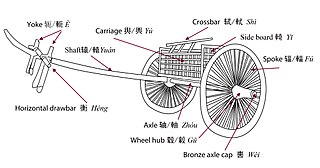

The ancient Chinese chariot was used as an attack and pursuit vehicle on the open fields and plains of ancient China from around 1200 BCE. Chariots also allowed military commanders a mobile platform from which to control troops while providing archers and soldiers armed with dagger-axes increased mobility. They reached a peak of importance during the Spring and Autumn period, but were largely superseded by cavalry during the Han dynasty.

The history of the Great Wall of China began when fortifications built by various states during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods were connected by the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, to protect his newly founded Qin dynasty against incursions by nomads from Inner Asia. The walls were built of rammed earth, constructed using forced labour, and by 212 BC ran from Gansu to the coast of southern Manchuria.

The conquest of the Western Turks, known as the Western Tujue in Chinese sources, was a military campaign in 655–657 led by the Tang dynasty generals Su Dingfang and Cheng Zhijie against the Western Turkic Khaganate ruled by Ashina Helu. The Tang campaigns against the Western Turks began in 640 with the annexation of the Tarim Basin oasis state Gaochang, an ally of the Western Turks. Several of the oasis states had once been vassals of the Tang dynasty, but switched their allegiance to the Western Turks when they grew suspicious of the military ambitions of the Tang. Tang expansion into Central Asia continued with the conquest of Karasahr in 644 and Kucha in 648. Cheng Zhijie commanded the first foray against the West Tujue, and in 657 Su Dingfang commanded the main army dispatched against the Western Turks, while the Turkic generals Ashina Mishe and Ashina Buzhen led the side divisions. The Tang troops were reinforced by cavalry supplied by the Uyghurs, a tribe that had been allied with the Tang since their support for the Uyghur revolt against the Xueyantuo. Su Dingfang's army defeated Helu at the battle of Irtysh River.

The Turco-Mongol sabre, alternatively known as the Eurasian sabre or nomadic sabre, was a type of sword used by a variety of nomadic peoples of the Eurasian steppes, including Turkic and Mongolic groups, primarily between the 8th and 14th centuries. One of the earliest recorded sabres of this type was recovered from an Avar grave in Romania dating to the mid-7th century.