Related Research Articles

In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of contradictory information and the mental toll of it. Relevant items of information include a person's actions, feelings, ideas, beliefs, values, and things in the environment. Cognitive dissonance is typically experienced as psychological stress when persons participate in an action that goes against one or more of those things. According to this theory, when two actions or ideas are not psychologically consistent with each other, people do all in their power to change them until they become consistent. The discomfort is triggered by the person's belief clashing with new information perceived, wherein the individual tries to find a way to resolve the contradiction to reduce their discomfort.

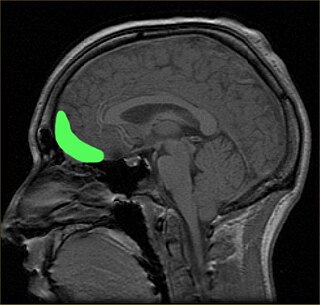

The limbic system, also known as the paleomammalian cortex, is a set of brain structures located on both sides of the thalamus, immediately beneath the medial temporal lobe of the cerebrum primarily in the forebrain.

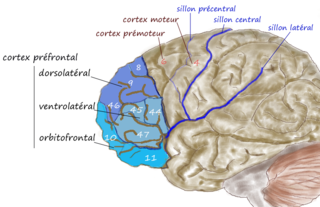

The frontal lobe is the largest of the four major lobes of the brain in mammals, and is located at the front of each cerebral hemisphere. It is parted from the parietal lobe by a groove between tissues called the central sulcus and from the temporal lobe by a deeper groove called the lateral sulcus. The most anterior rounded part of the frontal lobe is known as the frontal pole, one of the three poles of the cerebrum.

Self-control is an aspect of inhibitory control, one of the core executive functions. Executive functions are cognitive processes that are necessary for regulating one's behavior in order to achieve specific goals. Defined more independently, self-control is the ability to regulate one's emotions, thoughts, and behavior in the face of temptations and impulses. Thought to be like a muscle, acts of self-control expend a limited resource. In the short term, overuse of self-control leads to the depletion of that resource. However, in the long term, the use of self-control can strengthen and improve the ability to control oneself over time.

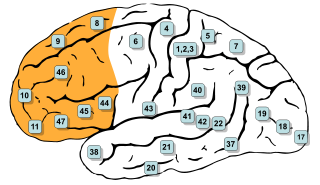

In mammalian brain anatomy, the prefrontal cortex (PFC) covers the front part of the frontal lobe of the cerebral cortex. The PFC contains the Brodmann areas BA8, BA9, BA10, BA11, BA12, BA13, BA14, BA24, BA25, BA32, BA44, BA45, BA46, and BA47.

The somatic marker hypothesis, formulated by Antonio Damasio and associated researchers, proposes that emotional processes guide behavior, particularly decision-making.

Affective neuroscience is the study of how the brain processes emotions. This field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The basis of emotions and what emotions are remains an issue of debate within the field of affective neuroscience.

Affect, in psychology, refers to the underlying experience of feeling, emotion, attachment, or mood. In psychology, "affect" refers to the experience of feeling or emotion. It encompasses a wide range of emotional states and can be positive or negative. Affect is a fundamental aspect of human experience and plays a central role in many psychological theories and studies. It can be understood as a combination of three components: emotion, mood, and affectivity. In psychology, the term "affect" is often used interchangeably with several related terms and concepts, though each term may have slightly different nuances. These terms encompass: emotion, feeling, mood, emotional state, sentiment, affective state, emotional response, affective reactivity, disposition. Researchers and psychologists may employ specific terms based on their focus and the context of their work.

In cognitive science and neuropsychology, executive functions are a set of cognitive processes that are necessary for the cognitive control of behavior: selecting and successfully monitoring behaviors that facilitate the attainment of chosen goals. Executive functions include basic cognitive processes such as attentional control, cognitive inhibition, inhibitory control, working memory, and cognitive flexibility. Higher-order executive functions require the simultaneous use of multiple basic executive functions and include planning and fluid intelligence.

The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is a prefrontal cortex region in the frontal lobes of the brain which is involved in the cognitive process of decision-making. In non-human primates it consists of the association cortex areas Brodmann area 11, 12 and 13; in humans it consists of Brodmann area 10, 11 and 47.

The ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) is a part of the prefrontal cortex in the mammalian brain. The ventral medial prefrontal is located in the frontal lobe at the bottom of the cerebral hemispheres and is implicated in the processing of risk and fear, as it is critical in the regulation of amygdala activity in humans. It also plays a role in the inhibition of emotional responses, and in the process of decision-making and self-control. It is also involved in the cognitive evaluation of morality.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is an area in the prefrontal cortex of the primate brain. It is one of the most recently derived parts of the human brain. It undergoes a prolonged period of maturation which lasts into adulthood. The DLPFC is not an anatomical structure, but rather a functional one. It lies in the middle frontal gyrus of humans. In macaque monkeys, it is around the principal sulcus. Other sources consider that DLPFC is attributed anatomically to BA 9 and 46 and BA 8, 9 and 10.

One way of thinking holds that the mental process of decision-making is rational: a formal process based on optimizing utility. Rational thinking and decision-making does not leave much room for emotions. In fact, emotions are often considered irrational occurrences that may distort reasoning.

In psychology and neuroscience, executive dysfunction, or executive function deficit, is a disruption to the efficacy of the executive functions, which is a group of cognitive processes that regulate, control, and manage other cognitive processes. Executive dysfunction can refer to both neurocognitive deficits and behavioural symptoms. It is implicated in numerous psychopathologies and mental disorders, as well as short-term and long-term changes in non-clinical executive control. Executive dysfunction is the mechanism underlying ADHD Paralysis, and in a broader context, it can encompass other cognitive difficulties like planning, organizing, initiating tasks and regulating emotions. It is a core characteristic of ADHD and can elucidate numerous other recognized symptoms.

Inhibitory control, also known as response inhibition, is a cognitive process – and, more specifically, an executive function – that permits an individual to inhibit their impulses and natural, habitual, or dominant behavioral responses to stimuli in order to select a more appropriate behavior that is consistent with completing their goals. Self-control is an important aspect of inhibitory control. For example, successfully suppressing the natural behavioral response to eat cake when one is craving it while dieting requires the use of inhibitory control.

Cognitive flexibility is an intrinsic property of a cognitive system often associated with the mental ability to adjust its activity and content, switch between different task rules and corresponding behavioral responses, maintain multiple concepts simultaneously and shift internal attention between them. The term cognitive flexibility is traditionally used to refer to one of the executive functions. In this sense, it can be seen as neural underpinnings of adaptive and flexible behavior. Most flexibility tests were developed under this assumption several decades ago. Nowadays, cognitive flexibility can also be referred to as a set of properties of the brain that facilitate flexible yet relevant switching between functional brain states.

Philip David Zelazo is a developmental psychologist and neuroscientist. His research has helped shape the field of developmental cognitive neuroscience regarding the development of executive function.

The neurocircuitry that underlies executive function processes and emotional and motivational processes are known to be distinct in the brain. However, there are brain regions that show overlap in function between the two cognitive systems. Brain regions that exist in both systems are interesting mainly for studies on how one system affects the other. Examples of such cross-modal functions are emotional regulation strategies such as emotional suppression and emotional reappraisal, the effect of mood on cognitive tasks, and the effect of emotional stimulation of cognitive tasks.

The dual systems model, also known as the maturational imbalance model, is a theory arising from developmental cognitive neuroscience which posits that increased risk-taking during adolescence is a result of a combination of heightened reward sensitivity and immature impulse control. In other words, the appreciation for the benefits arising from the success of an endeavor is heightened, but the appreciation of the risks of failure lags behind.

Social cognitive neuroscience is the scientific study of the biological processes underpinning social cognition. Specifically, it uses the tools of neuroscience to study "the mental mechanisms that create, frame, regulate, and respond to our experience of the social world". Social cognitive neuroscience uses the epistemological foundations of cognitive neuroscience, and is closely related to social neuroscience. Social cognitive neuroscience employs human neuroimaging, typically using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Human brain stimulation techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation and transcranial direct-current stimulation are also used. In nonhuman animals, direct electrophysiological recordings and electrical stimulation of single cells and neuronal populations are utilized for investigating lower-level social cognitive processes.

References

- 1 2 3 Brand, A. G. (1985–1986), "Hot cognition: Emotions and writing behavior", JAC, 6: 5–15, JSTOR 20865583

- ↑ Roiser JP, Sahakian BJ (2013). "Hot and cold cognition in depression". CNS Spectr. 18 (3): 139–49. doi:10.1017/S1092852913000072. PMID 23481353. S2CID 34123889.

- ↑ Lodge, Milton; Taber, Charles S. (2005). "The Automaticity of Affect for Political Leaders, Groups, and Issues: An Experimental Test of the Hot Cognition Hypothesis". Political Psychology. 26 (3): 455–482. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2005.00426.x. ISSN 0162-895X.

- ↑ Huijbregts, Stephan C. J.; Warren, Alison J.; Sonneville, Leo M. J.; Swaab-Barneveld, Hanna (2007). "Hot and Cool Forms of Inhibitory Control and Externalizing Behavior in Children of Mothers who Smoked during Pregnancy: An Exploratory Study". Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 36 (3): 323–333. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9180-x . ISSN 0091-0627. PMC 2268722 . PMID 17924184.

- ↑ Kunda, Ziva (1990). "The case for motivated reasoning". Psychological Bulletin. 108 (3): 480–498. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.108.3.480. ISSN 0033-2909. PMID 2270237. S2CID 9703661.

- 1 2 Roiser, J.P. (2013), "Hot and cold cognition in depression", Journal of Neuroscience Education Institute, 18 (3): 1092–8529, doi:10.1017/S1092852913000072, ISSN 1092-8529, PMID 23481353, S2CID 34123889

- 1 2 Zelazo, Philip David; Mller, Ulrich (2002). "Executive Function in Typical and Atypical Development". Blackwell Handbook of Childhood Cognitive Development. pp. 445–469. doi:10.1002/9780470996652.ch20. ISBN 9780470996652.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hongwanishkul, Donaya; Happaney, Keith R.; Lee, Wendy S. C.; Zelazo, Philip David (2005). "Assessment of Hot and Cool Executive Function in Young Children: Age-Related Changes and Individual Differences". Developmental Neuropsychology. 28 (2): 617–644. doi:10.1207/s15326942dn2802_4. ISSN 8756-5641. PMID 16144430. S2CID 30614220.

- ↑ Diamond, Adele (2002). "Normal Development of Prefrontal Cortex from Birth to Young Adulthood: Cognitive Functions, Anatomy, and Biochemistry". Principles of Frontal Lobe Function. pp. 466–503. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195134971.003.0029. ISBN 9780195134971.

- ↑ Prencipe, Angela; Kesek, Amanda; Cohen, Julia; Lamm, Connie; Lewis, Marc D.; Zelazo, Philip David (2011). "Development of hot and cool executive function during the transition to adolescence". Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 108 (3): 621–637. doi:10.1016/j.jecp.2010.09.008. ISSN 0022-0965. PMID 21044790.

- 1 2 Zelazo, Philip David; Carlson, Stephanie M. (2012). "Hot and Cool Executive Function in Childhood and Adolescence: Development and Plasticity". Child Development Perspectives: n/a. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00246.x . ISSN 1750-8592.

- ↑ Sato, Shintaro; Ko, Yong Jae; Kellison, Timothy B (17 September 2017). "Hot or Cold? The Effects of Anger and Perceived Responsibility on Sport Fans' Negative Word-of-Mouth in Athlete Scandals". Journal of Global Sport Management. 3 (2): 107–123. doi:10.1080/24704067.2018.1432984. S2CID 148850760 . Retrieved 3 May 2021.

In the field of consumer research, scholars have commonly examined how 'hot' and 'cold' cognition influence consumers' behavioral response towards certain events such as sporting games (Biscaia, Correia, Rosado, Maroco, & Ross, 2012; Madrigal, 2008). Hot cognition is a less conscious, quick, and automatic decision process often operationalized as emotion while cold cognition is regarded as fact-based conscious processing, operationalized as cognition (Ask & Granhag, 2007; Hammond, 1996; Madrigal, 2008; Metcalfe & Mischel, 1999).

- 1 2 Goel, V.; Vartanian, O. (2011). "Negative emotions can attenuate the influence of beliefs on logical reasoning". Cognition and Emotion. 25 (1): 121–131. doi:10.1080/02699931003593942. PMID 21432659. S2CID 21884466.

- ↑ Madrigal, R (2008). "Hot vs. cold cognitions and consumers' reactions to sporting event outcomes". Journal of Consumer Psychology. 18 (4): 304–319. doi:10.1016/j.jcps.2008.09.008. ISSN 1057-7408.

- ↑ Ask, Karl; Granhag, Pär Anders (2007). "Hot cognition in investigative judgments: The differential influence of anger and sadness". Law and Human Behavior. 31 (6): 537–551. doi:10.1007/s10979-006-9075-3. ISSN 1573-661X. PMID 17160487. S2CID 42104187.

- ↑ Roiser, Jonathan P; Cannon, Dara M; Gandhi, Shilpa K; Tavares, Joana Taylor; Erickson, Kristine; Wood, Suzanne; Klaver, Jacqueline M; Clark, Luke; Zarate Jr, Carlos A; Sahakian, Barbara J; Drevets, Wayne C (2009). "Hot and cold cognition in unmedicated depressed subjects with bipolar disorder". Bipolar Disorders. 11 (2): 178–189. doi:10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00669.x. ISSN 1398-5647. PMC 2670985 . PMID 19267700.