A capital gains tax (CGT) is the tax on profits realized on the sale of a non-inventory asset. The most common capital gains are realized from the sale of stocks, bonds, precious metals, real estate, and property.

Liquidation is the process in accounting by which a company is brought to an end. The assets and property of the business are redistributed. When a firm has been liquidated, it is sometimes referred to as wound-up or dissolved, although dissolution technically refers to the last stage of liquidation. The process of liquidation also arises when customs, an authority or agency in a country responsible for collecting and safeguarding customs duties, determines the final computation or ascertainment of the duties or drawback accruing on an entry.

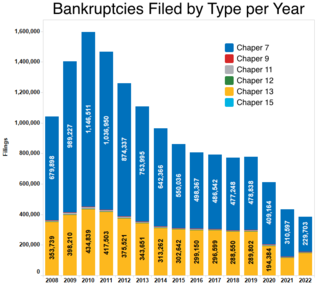

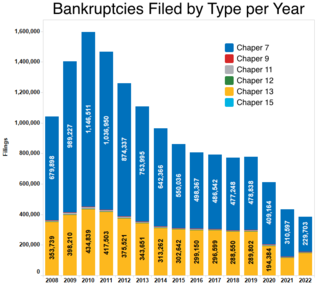

In the United States, bankruptcy is largely governed by federal law, commonly referred to as the "Bankruptcy Code" ("Code"). The United States Constitution authorizes Congress to enact "uniform Laws on the subject of Bankruptcies throughout the United States". Congress has exercised this authority several times since 1801, including through adoption of the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978, as amended, codified in Title 11 of the United States Code and the Bankruptcy Abuse Prevention and Consumer Protection Act of 2005 (BAPCPA).

In accounting, insolvency is the state of being unable to pay the debts, by a person or company (debtor), at maturity; those in a state of insolvency are said to be insolvent. There are two forms: cash-flow insolvency and balance-sheet insolvency.

In finance, a floating charge is a security interest over a fund of changing assets of a company or other legal person. Unlike a fixed charge, which is created over ascertained and definite property, a floating charge is created over property of an ambulatory and shifting nature, such as receivables and stock.

Nonrecourse debt or a nonrecourse loan is a secured loan (debt) that is secured by a pledge of collateral, typically real property, but for which the borrower is not personally liable. If the borrower defaults, the lender can seize and sell the collateral, but if the collateral sells for less than the debt, the lender cannot seek that deficiency balance from the borrower—its recovery is limited only to the value of the collateral. Thus, nonrecourse debt is typically limited to 50% or 60% loan-to-value ratios, so that the property itself provides "overcollateralization" of the loan.

1231 Property is a category of property defined in section 1231 of the U.S. Internal Revenue Code. 1231 property includes depreciable property and real property used in a trade or business and held for more than one year. Some types of livestock, coal, timber and domestic iron ore are also included. It does not include: inventory; property held for sale in the ordinary course of business; artistic creations held by their creator; or, government publications.

Under Section 1031 of the United States Internal Revenue Code, a taxpayer may defer recognition of capital gains and related federal income tax liability on the exchange of certain types of property, a process known as a 1031 exchange. In 1979, this treatment was expanded by the courts to include non-simultaneous sale and purchase of real estate, a process sometimes called a Starker exchange.

As a legal concept, administration is a procedure under the insolvency laws of a number of common law jurisdictions, similar to bankruptcy in the United States. It functions as a rescue mechanism for insolvent entities and allows them to carry on running their business. The process – in the United Kingdom colloquially called being "under administration" – is an alternative to liquidation or may be a precursor to it. Administration is commenced by an administration order.

In the United States, individuals and corporations pay a tax on the net total of all their capital gains. The tax rate depends on both the investor's tax bracket and the amount of time the investment was held. Short-term capital gains are taxed at the investor's ordinary income tax rate and are defined as investments held for a year or less before being sold. Long-term capital gains, on dispositions of assets held for more than one year, are taxed at a lower rate.

Taxpayers in the United States may have tax consequences when debt is cancelled. This is commonly known as cancellation-of-debt (COD) income. According to the Internal Revenue Code, the discharge of indebtedness must be included in a taxpayer's gross income. There are exceptions to this rule, however, so a careful examination of one's COD income is important to determine any potential tax consequences.

Depreciation recapture is the USA Internal Revenue Service (IRS) procedure for collecting income tax on a gain realized by a taxpayer when the taxpayer disposes of an asset that had previously provided an offset to ordinary income for the taxpayer through depreciation. In other words, because the IRS allows a taxpayer to deduct the depreciation of an asset from the taxpayer's ordinary income, the taxpayer has to report any gain from the disposal of the asset as ordinary income, not as a capital gain.

Arkansas Best Corporation v. Commissioner, 485 U.S. 212 (1988), is a United States Supreme Court decision that helps taxpayers classify whether or not the sale of an asset is an ordinary or capital gain or loss for income tax purposes.

Arrowsmith v. Commissioner, 344 U.S. 6 (1952), is a United States Supreme Court case regarding taxation. The case involves taxpayers who liquidated a corporation in 1937. The taxpayers (properly) reported the income from the liquidation as long-term capital gains, thus obtaining a preferential tax rate. Subsequent to the liquidation in 1944, the taxpayers were required to pay a judgment arising from the affairs of the liquidated corporation. The taxpayers classified this payment as an ordinary business loss, which would allow them to take a greater deduction for the loss than would be permitted for a capital loss.

United Kingdom insolvency law regulates companies in the United Kingdom which are unable to repay their debts. While UK bankruptcy law concerns the rules for natural persons, the term insolvency is generally used for companies formed under the Companies Act 2006. Insolvency means being unable to pay debts. Since the Cork Report of 1982, the modern policy of UK insolvency law has been to attempt to rescue a company that is in difficulty, to minimise losses and fairly distribute the burdens between the community, employees, creditors and other stakeholders that result from enterprise failure. If a company cannot be saved it is liquidated, meaning that the assets are sold off to repay creditors according to their priority. The main sources of law include the Insolvency Act 1986, the Insolvency Rules 1986, the Company Directors Disqualification Act 1986, the Employment Rights Act 1996 Part XII, the EU Insolvency Regulation, and case law. Numerous other Acts, statutory instruments and cases relating to labour, banking, property and conflicts of laws also shape the subject.

Bankruptcy in Irish Law is a legal process, supervised by the High Court whereby the assets of a personal debtor are realised and distributed amongst his or her creditors in cases where the debtor is unable or unwilling to pay his debts.

The British Virgin Islands company law is the law that governs businesses registered in the British Virgin Islands. It is primarily codified through the BVI Business Companies Act, 2004, and to a lesser extent by the Insolvency Act, 2003 and by the Securities and Investment Business Act, 2010. The British Virgin Islands has approximately 30 registered companies per head of population, which is likely the highest ratio of any country in the world. Annual company registration fees provide a significant part of Government revenue in the British Virgin Islands, which accounts for the comparative lack of other taxation. This might explain why company law forms a much more prominent part of the law of the British Virgin Islands when compared to countries of similar size.

Cayman Islands bankruptcy law is principally codified in five statutes and statutory instruments:

Ayerst v C&K (Construction) Ltd [1976] AC 167 was a decision of the House of Lords relating to revenue law and insolvency law which confirmed that where a company goes into insolvent liquidation it ceases to be the beneficial owner of its assets, and the liquidator holds those assets on a special "statutory trust" for the company's creditors.

An Opportunity Zone is a designation and investment program created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 allowing for certain investments in lower income areas to have tax advantages. The purpose of this program is to put capital to work that would otherwise be locked up due to the asset holder's unwillingness to trigger a capital gains tax.