Books of hours are Christian prayer books, which were used to pray the canonical hours. The use of a book of hours was especially popular in the Middle Ages, and as a result, they are the most common type of surviving medieval illuminated manuscript. Like every manuscript, each manuscript book of hours is unique in one way or another, but most contain a similar collection of texts, prayers and psalms, often with appropriate decorations, for Christian devotion. Illumination or decoration is minimal in many examples, often restricted to decorated capital letters at the start of psalms and other prayers, but books made for wealthy patrons may be extremely lavish, with full-page miniatures. These illustrations would combine picturesque scenes of country life with sacred images.

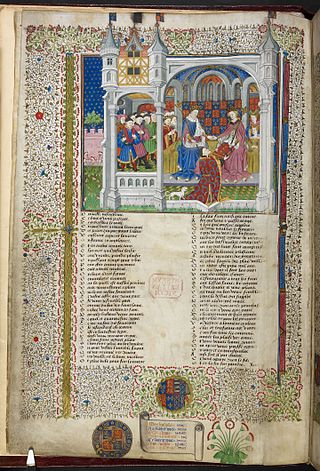

The Froissart of Louis of Gruuthuse is a heavily illustrated deluxe illuminated manuscript in four volumes, containing a French text of Froissart's Chronicles, written and illuminated in the first half of the 1470s in Bruges, Flanders, in modern Belgium. The text of Froissart's Chronicles is preserved in more than 150 manuscript copies. This is one of the most lavishly illuminated examples, commissioned by Louis of Gruuthuse, a Flemish nobleman and bibliophile. Several leading Flemish illuminators worked on the miniatures.

Simon Bening was a Flemish miniaturist, generally regarded as the last major artist of the Netherlandish tradition.

Simon Marmion was a French and Burgundian Early Netherlandish painter of panels and illuminated manuscripts. Marmion lived and worked in what is now France but for most of his lifetime was part of the Duchy of Burgundy in the Southern Netherlands.

The Turin–Milan Hours is a partially destroyed illuminated manuscript, which despite its name is not strictly a book of hours. It is of exceptional quality and importance, with a very complicated history both during and after its production. It contains several miniatures of about 1420 attributed to an artist known as "Hand G" who was probably either Jan van Eyck, his brother Hubert van Eyck, or an artist very closely associated with them. About a decade or so later Barthélemy d'Eyck may have worked on some miniatures. Of the several portions of the book, that kept in Turin was destroyed in a fire in 1904, though black-and-white photographs exist.

The Rothschild Prayerbook or Rothschild Hours, is an important Flemish illuminated manuscript book of hours, compiled c. 1500–1520 by a number of artists.

The Grandes Heures of Anne of Brittany is a book of hours, commissioned by Anne of Brittany, Queen of France to two kings in succession, and illuminated in Tours or perhaps Paris by Jean Bourdichon between 1503 and 1508. It has been described by John Harthan as "one of the most magnificent Books of Hours ever made", and is now in the Bibliothèque nationale de France, catalogued as Ms lat. 9474. It has 49 full-page miniatures in a Renaissance style, and more than 300 pages have large borders illustrated with a careful depiction of, usually, a single species of plant.

Janet Moira Backhouse was an English manuscripts curator at the British Museum, and a leading authority in the field of illuminated manuscripts.

The Hours of Étienne Chevalier is an illuminated book of hours commissioned by Étienne Chevalier, treasurer to king Charles VII of France, from the miniature painter and illuminator Jean Fouquet.

Jean Poyer, was a French painter and manuscript illuminator of the late 15th century. As a multitalented artist - illuminator, painter, draftsman, and festival designer active from 1483 until his death - he was a painter of Renaissance France, working for the courts of three successive French kings: Louis XI, Charles VIII, and Louis XII.

Jean Bourdichon was a French painter and manuscript illuminator at the court of France between the end of the 15th century and the start of the 16th century, in the reigns of Louis XI of France, Charles VIII of France, Louis XII of France, and Francis I of France. He was probably born in Tours, and was a pupil of Jean Fouquet. He died in Tours.

The Royal manuscripts are one of the "closed collections" of the British Library, consisting of some 2,000 manuscripts collected by the sovereigns of England in the "Old Royal Library" and given to the British Museum by George II in 1757. They are still catalogued with call numbers using the prefix "Royal" in the style "Royal MS 2. B. V". As a collection, the Royal manuscripts date back to Edward IV, though many earlier manuscripts were added to the collection before it was donated. Though the collection was therefore formed entirely after the invention of printing, luxury illuminated manuscripts continued to be commissioned by royalty in England as elsewhere until well into the 16th century. The collection was expanded under Henry VIII by confiscations in the Dissolution of the Monasteries and after the falls of Henry's ministers Cardinal Wolsey and Thomas Cromwell. Many older manuscripts were presented to monarchs as gifts; perhaps the most important manuscript in the collection, the Codex Alexandrinus, was presented to Charles I in recognition of the diplomatic efforts of his father James I to help the Eastern Orthodox churches under the rule of the Ottoman Empire. The date and means of entry into the collection can only be guessed at in many if not most cases. Now the collection is closed in the sense that no new items have been added to it since it was donated to the nation.

The Bedford Hours is a French late medieval book of hours. It dates to the early fifteenth century (c. 1410–30); some of its miniatures, including the portraits of the Duke and Duchess of Bedford, have been attributed to the Bedford Master and his workshop in Paris. The Duke and Duchess of Bedford gave the book to their nephew Henry VI in 1430. It is in the British Library, catalogued as Add MS 18850.

The Hours of Joanna I of Castile is a sixteenth-century illuminated codex housed in the British Library, London, under call number Add MS 35313.

The Book of Hours of Simon de Varie is a French illuminated manuscript book of hours commissioned by the court official Simon de Varie, with miniatures attributed to at least four artists; hand A who may have been a workshop member of the Bedford Master, the anonymous illustrators known as the Master of Jean Rolin II, the Dunois Master and the French miniaturist Jean Fouquet. It was completed in 1455 and consists of 49 large miniatures and dozens of decorative vignettes and painted initials, which total over 80 decorations. Fouquet is known to have contributed six full leaf illuminations, including a masterwork Donor and Virgin diptych. A number of saints appear - Saint Simon is placed as usual alongside Saint Jude ; other pages feature saints Bernard of Menthon, James the Greater and Guillaume de Bourges.

A presentation miniature or dedication miniature is a miniature painting often found in illuminated manuscripts, in which the patron or donor is presented with a book, normally to be interpreted as the book containing the miniature itself. The miniature is thus symbolic, and presumably represents an event in the future. Usually it is found at the start of the volume, as a frontispiece before the main text, but may also be placed at the end, as in the Vivian Bible, or at the start of a particular text in a collection.

The Pseudo-Jacquemart was an anonymous master illuminator active in Paris and Bourges between 1380 and 1415. He owed his name to his close collaboration with painter Jacquemart de Hesdin.

The Munich-Montserrat Book of Hours is a 1535 illuminated manuscript book of hours. It measured 10 by 14 cm in its original form. It was produced by Simon Bening and his workshop, possibly for Alonso de Idiaquez, royal secretary to Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor. Its miniatures are stylistically similar to other books of hours by Bening and his workshop, such as the Da Costa Book of Hours, the Hennessy Book of Hours and the Hours of Isabella of Portugal, all produced for Spanish nobles.

The Spinola Hours is a illuminated manuscript book of hours of about 1510-1520, consisting of 312 folios, over 80 of which are mainly decorated with miniature paintings. It was produced between Bruges and Ghent in Flanders around 1510-1520, and is a key work of the Ghent–Bruges school of illuminators. According to Thomas Kren, a former curator of the J. Paul Getty Museum, the miniatures within the Spinola Hours can be attributed to five distinct sources. Forty-seven of these illuminated pages can be attributed to the 'Master of James IV'. Since 1883 it has been in the J. Paul Getty Museum in Malibu, catalogued as Ms. Ludwig IX 18 (83.ML.114).

The Book of hours of Frederick of Aragon or simply the Hours of Frederick of Aragon is a luxury book of hours, a private devotional book, made for Frederick of Aragon between 1501 and 1502. Described as a "particularly accomplished work of art", it is the result of cooperation between three different artists, Ioan Todeschino, Jean Bourdichon, and the Master of Claude de France. The 62 full-page miniatures were made by Bourdichon, and have been described as some of his best work, while the border decorations were made by Todeschino and the Master of Claude de France. Following the death of Frederick, the book probably eventually ended up in Spain, and eventually entered the library of Joseph Bonaparte. It was eventually lost by him and finally bought by the predecessor of today's Bibliothèque nationale de France, the French national library, in 1828. It is kept in the library collections in Paris and has been exhibited to the public on several occasions.