The Revolutions of 1848 in the Austrian Empire were a set of revolutions that took place in the Austrian Empire from March 1848 to November 1849. Much of the revolutionary activity had a nationalist character: the Empire, ruled from Vienna, included ethnic Germans, Hungarians, Poles, Bohemians (Czechs), Ruthenians (Ukrainians), Slovenes, Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Italians, and Serbs; all of whom attempted in the course of the revolution to either achieve autonomy, independence, or even hegemony over other nationalities. The nationalist picture was further complicated by the simultaneous events in the German states, which moved toward greater German national unity.

Lajos Kossuth de Udvard et Kossuthfalva was a Hungarian nobleman, lawyer, journalist, politician, statesman and governor-president of the Kingdom of Hungary during the revolution of 1848–1849.

Artúr Görgei de Görgő et Toporc was a Hungarian military leader renowned for being one of the greatest generals of the Hungarian Revolutionary Army.

The Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867 established the dual monarchy of Austria-Hungary, which was a military and diplomatic alliance of two sovereign states. The Compromise only partially re-established the former pre-1848 sovereignty and status of the Kingdom of Hungary, being separate from, and no longer subject to, the Austrian Empire. The compromise put an end to the 18-year-long military dictatorship and absolutist rule over Hungary which Emperor Franz Joseph had instituted after the Hungarian Revolution of 1848. The territorial integrity of the Kingdom of Hungary was restored. The agreement also restored the old historic constitution of the Kingdom of Hungary.

Ferenc Deák de Kehida was a Hungarian statesman and Minister of Justice. He was known as "The Wise Man of the Nation" and one of the greatest figures of Hungary's liberal movement.

Count Josip Jelačić von Bužim was a Croatian lieutenant field marshal in the Imperial Austrian Army and politician. He was the Ban of Croatia between 23 March 1848 and 19 April 1859. He was a member of the House of Jelačić and a noted army general, remembered for his military campaigns during the Revolutions of 1848 and for his abolition of serfdom in Croatia.

The Kingdom of Hungary between 1526 and 1867 existed as a state outside the Holy Roman Empire, but part of the lands of the Habsburg monarchy that became the Austrian Empire in 1804. After the Battle of Mohács in 1526, the country was ruled by two crowned kings. Initially, the exact territory under Habsburg rule was disputed because both rulers claimed the whole kingdom. This unsettled period lasted until 1570 when John Sigismund Zápolya abdicated as King of Hungary in Emperor Maximilian II's favor.

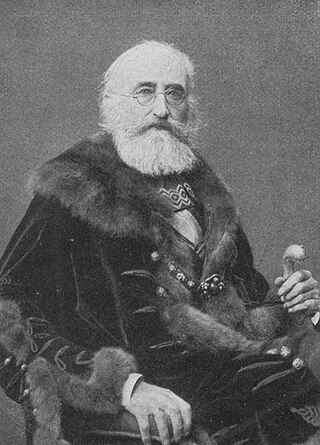

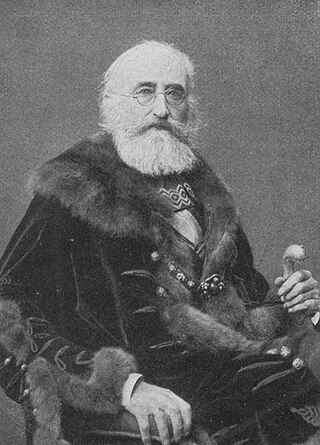

Kálmán Tisza de Borosjenő was a Hungarian politician during the Austro-Hungarian empire who served as the Hungarian prime minister between 1875 and 1890. He is credited with the formation of a consolidated Hungarian government, the foundation of the new Liberal Party (1875) and major economic reforms that would both save and eventually lead to a government with popular support. He is the second longest-serving head of government in Hungarian history.

Robert John Weston Evans is a British historian, whose speciality is the post-medieval history of Central and Eastern Europe.

Funérailles is the 7th and one of the most famous pieces in Harmonies poétiques et religieuses, a collection of piano pieces by Franz Liszt. It was an elegy written in October 1849 in response to the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848 by the Habsburgs.

The Hungarian Revolution of 1848, also known in Hungary as Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence of 1848–1849 was one of many European Revolutions of 1848 and was closely linked to other revolutions of 1848 in the Habsburg areas. Although the revolution failed, it is one of the most significant events in Hungary's modern history, forming the cornerstone of modern Hungarian national identity—the anniversary of the Revolution's outbreak, 15 March, is one of Hungary's three national holidays.

The revolutions of 1848, known in some countries as the springtime of the peoples or the springtime of nations, were a series of revolutions throughout Europe over the course of more than one year, from 1848 to 1849. It remains the most widespread revolutionary wave in European history to date.

The rise of nationalism in Europe was stimulated by the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. American political science professor Leon Baradat has argued that “nationalism calls on people to identify with the interests of their national group and to support the creation of a state – a nation-state – to support those interests.” Nationalism was the ideological impetus that, in a few decades, transformed Europe. Rule by monarchies and foreign control of territory was replaced by self-determination and newly formed national governments. Some countries, such as Germany and Italy were formed by uniting various regional states with a common "national identity". Others, such as Greece, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Poland were formed by uprisings against the Ottoman or Russian Empires. Romania is a special case, formed by the unification of the principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia in 1859 and later gaining independence from the Ottoman Empire in 1878.

The New German School is a term introduced in 1859 by Franz Brendel, editor of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, to describe certain trends in German music. Although the term has frequently been used in essays and books about music history of the 19th and early 20th centuries, a clear definition is complex.

Franz Liszt wrote his symphonic poem Hungaria in 1854, basing it partly on the Heroic March in the Hungarian Style for piano which he wrote in 1840. It was premiered under Liszt's baton at the Hungarian National Theater in Budapest on September 8, 1856, where it achieved an enormous success. "There was better than applause," the composer later wrote. "All wept, both men and women!" He was reminded with that scene of the proverb that "tears are the joy of the Hungarians."

István Deák was a Hungarian-born American historian, author and academic. He was a specialist in modern Europe, with special attention to Germany and Hungary.

The March Constitution, also called Imposed March Constitution or Stadion Constitution, was a constitution of the Austrian Empire promulgated by Minister of the Interior Count Stadion between 4 March and 7 March 1849. Though declared irrevocable, it was eventually revoked by the New Year's Eve Patent of Emperor Franz Joseph I on 31 December 1851. The Stadion Constitution emphasized power for the monarch; it also marked the way of the neo-absolutism in the Habsburg ruled territories. It preempted the Kremsier Constitution of the Kremsier Parliament. This state of affairs would last until the October Diploma of 20 October 1860 and the later February Patent of 26 February 1861.

The Slovak Uprising , Slovak Volunteer Campaigns, Slovak Revolt or the Slovak Revolution was an uprising of Slovaks in Western parts of Upper Hungary with the aim of equalizing Slovaks, democratizing political life and achieving social justice within the 1848–49 revolutions in the Habsburg Monarchy. It lasted from September 1848 to November 1849. In October 1848, Slovak leaders replaced their original Hungaro-federal program by Austro-federal, called for the separation of a Slovak district from the Kingdom of Hungary and for the formation of a new autonomous district within the framework of the Habsburg Monarchy.

Pál Almásy de Zsadány et Törökszentmiklós was a Hungarian lawyer and politician, who served as Speaker of the House of Representatives in 1849.

The Hungarian State was a short-lived unrecognised state that existed for 4 months in the last phase of the Hungarian Revolution of 1848–49.