The Constitution of the Irish Free State was adopted by Act of Dáil Éireann sitting as a constituent assembly on 25 October 1922. In accordance with Article 83 of the Constitution, the Irish Free State Constitution Act 1922 of the British Parliament, which came into effect upon receiving the royal assent on 5 December 1922, provided that the Constitution would come into effect upon the issue of a Royal Proclamation, which was done on 6 December 1922. In 1937 the Constitution of the Irish Free State was replaced by the modern Constitution of Ireland following a referendum.

A constitutional amendment is a modification of the constitution of a polity, organization or other type of entity. Amendments are often interwoven into the relevant sections of an existing constitution, directly altering the text. Conversely, they can be appended to the constitution as supplemental additions (codicils), thus changing the frame of government without altering the existing text of the document.

A constituent assembly or constitutional assembly is a body or assembly of popularly elected representatives composed for the purpose of drafting or adopting a constitutional-type document. The constituent assembly is a subset of a constitutional convention elected entirely by popular vote; that is, all constituent assemblies are constitutional conventions, but a constitutional convention is not necessarily a constituent assembly. As the fundamental document constituting a state, a constitution cannot normally be modified or amended by the state's normal legislative procedures; instead a constitutional convention or a constituent assembly, the rules for which are normally laid down in the constitution, must be set up. A constituent assembly is usually set up for its specific purpose, which it carries out in a relatively short time, after which the assembly is dissolved. A constituent assembly is a form of representative democracy.

The President of the Arab Republic of Egypt is the head of state of Egypt. Under the various iterations of the Constitution of Egypt, the president is also the Supreme Commander of the Armed Forces and head of the executive branch of the Egyptian government. The current president is Abdel Fattah el-Sisi, in office since 8 June 2014.

Election law is a discipline falling at the juncture of constitutional law and political science. It researches "the politics of law and the law of politics". The conceptual knowledge behind election law focuses on who votes, when that person can vote, and the construction behind the tabulated totals.

The Constitutional Council is the highest constitutional authority in France. It was established by the Constitution of the Fifth Republic on 4 October 1958 and its duty is to ensure that constitutional principles and rules are upheld. It is housed in the Palais-Royal, Paris.

The Constitution of the State of Tennessee defines the form, structure, activities, character, and fundamental rules of the U.S. State of Tennessee.

The Constitution of Colombia, better known as the Constitution of 1991, is the current governing document of the Republic of Colombia. Promulgated on July 4, 1991, it replaced the Constitution of 1886. It is Colombia's ninth constitution since 1830. See a timeline of all previous constitutions and amendments here. It has recently been called the Constitution of Rights.

The Constitutional Act of the Kingdom of Denmark, or simply the Constitution, is the constitution of the Kingdom of Denmark, applying equally in Denmark proper, Greenland and the Faroe Islands. In its present form, the Constitutional Act is from 1953, but the principal features of the Act go back to 1849, making it one of the oldest constitutions.

The Constitution of the State of Arkansas is the governing document of the U.S. state of Arkansas. It was adopted in 1874, shortly after the Brooks-Baxter War. It replaced the 1868 constitution adopted by the legislature following the end of the American Civil War and under which Arkansas rejoined the Union.

The Constitution of the Republic of Belarus is the ultimate law of Belarus. Adopted in 1994, three years after the country declared its independence from the Soviet Union, this formal document establishes the framework of the Belarusian state and government and enumerates the rights and freedoms of its citizens. The Constitution was drafted by the Supreme Soviet of Belarus, the former legislative body of the country, and was improved upon by citizens and legal experts. The contents of the Constitution include the preamble, nine sections, and 146 articles.

The President of Montenegro is the head of state of Montenegro. The current president is Milo Đukanović, who was elected in the first round of the 2018 presidential election with 53.90% of the vote. The official residence of the President is the Blue Palace located in the former royal capital Cetinje.

Term limits legislation – term limits for state and federal office-holders – has been a recurring political issue in the U.S. state of Oregon since 1992. In that year's general election, Oregon voters approved Ballot Measure 3, an initiative that enacted term limits for representatives in both houses of the United States Congress and the Oregon Legislative Assembly, and statewide officeholders. It has been described as the strictest term limits law in the country.

Proposition 7 of 1911 was an amendment of the Constitution of California that introduced, for the first time, the initiative and the optional referendum. Prior to 1911 the only form of direct democracy in California was the compulsory referendum.

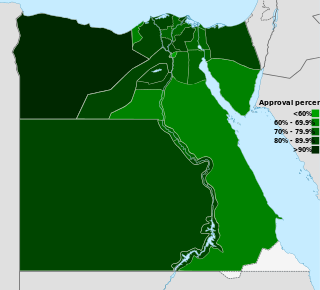

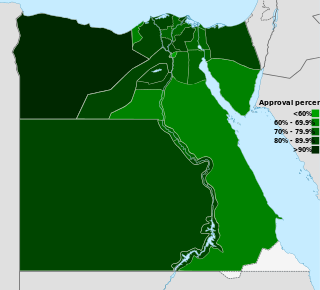

A constitutional referendum was held in Egypt on 19 March 2011, following the 2011 Egyptian revolution. More than 14 million (77%) were in favour, while around 4 million (23%) opposed the changes; 41% of 45 million eligible voters turned out to vote.

An Icelandic Constitutional Council (Stjórnlagaráð) for the purpose of reviewing the Constitution of the Republic was appointed by a resolution of Althingi, the Icelandic parliament, on 24 March 2011. Elections were held to create a Constitutional Assembly (Stjórnlagaþing) body, but given some electoral flaws, had been ruled null and void by the Supreme Court of Iceland on 25 January 2011, leading the parliament to place most of the wining candidate into a Council with similar mission. The question of whether the text of the proposed constitution should form a base for a future constitution was put to a non-binding referendum, where it won the approval of 67% of voters. However, the government's term finished before the reform bill could be passed, and the next government has not acted upon it.

The Basic Laws of Israel are the constitutional laws of the State of Israel, and can only be changed by a supermajority vote in the Knesset. Many of these laws are based on the individual liberties that were outlined in the Israeli Declaration of Independence. The Basic Laws deal with the formation and role of the principal institutions of the state, and with the relations between the state's authorities. They also protect the country's civil rights, although some of these rights were earlier protected at common law by the Supreme Court of Israel. The Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty enjoys super-legal status, giving the Supreme Court the authority to disqualify any law contradicting it, as well as protection from Emergency Regulations.

Marsy's Law for Illinois, formally called the Illinois Crime Victims' Bill of Rights, amended the 1993 Rights of Crime Victims and Witnesses Act by establishing additional protections for crime victims and their families. Voters approved the measure as a constitutional amendment on November 4, 2014. It became law in 2015.