Lagash was an ancient city-state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Ninurta (Sumerian: 𒀭𒊩𒌆𒅁: DNIN.URTA, possible meaning "Lord [of] Barley"), also known as Ninĝirsu (Sumerian: 𒀭𒎏𒄈𒋢: DNIN.ĜIR2.SU, meaning "Lord [of] Girsu"), is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with farming, healing, hunting, law, scribes, and war who was first worshipped in early Sumer. In the earliest records, he is a god of agriculture and healing, who cures humans of sicknesses and releases them from the power of demons. In later times, as Mesopotamia grew more militarized, he became a warrior deity, though he retained many of his earlier agricultural attributes. He was regarded as the son of the chief god Enlil and his main cult center in Sumer was the Eshumesha temple in Nippur. Ninĝirsu was honored by King Gudea of Lagash (ruled 2144–2124 BC), who rebuilt Ninĝirsu's temple in Lagash. Later, Ninurta became beloved by the Assyrians as a formidable warrior. The Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (ruled 883–859 BC) built a massive temple for him at Kalhu, which became his most important cult center from then on.

Bau (cuneiform: 𒀭𒁀𒌑 dBa-U2; also romanized as Baba or Babu) was a Mesopotamian goddess. The reading of her name is a subject of debate among researchers, though Bau is considered the conventional spelling today. While initially regarded simply as a life-giving deity, in some cases associated with the creation of mankind, over the course of the third and second millennia BCE she also acquired the role of a healing goddess. She could be described as a divine midwife. In art she could be depicted in the company of waterfowl or scorpions.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Nanshe was a Mesopotamian goddess in various contexts associated with the sea, marshlands, the animals inhabiting these biomes, namely bird and fish, as well as divination, dream interpretation, justice, social welfare, and certain administrative tasks. She was regarded as a daughter of Enki and sister of Ningirsu, while her husband was Nindara, who is otherwise little known. Other deities who belonged to her circle included her daughter Nin-MAR.KI, as well as Hendursaga, Dumuzi-abzu and Shul-utula. In Ur she was incorporated into the circle of Ningal, while in incantations she appears alongside Ningirima or Nammu.

Ningishzida was a Mesopotamian deity of vegetation, the underworld and sometimes war. He was commonly associated with snakes. Like Dumuzi, he was believed to spend a part of the year in the land of the dead. He also shared many of his functions with his father Ninazu.

Ninshubur, also spelled Ninšubura, was a Mesopotamian goddess whose primary role was that of the sukkal of the goddess Inanna. While it is agreed that in this context Ninshubur was regarded as female, in other cases the deity was considered male, possibly due to syncretism with other divine messengers, such as Ilabrat. No certain information about her genealogy is present in any known sources, and she was typically regarded as unmarried. As a sukkal, she functioned both as a messenger deity and as an intercessor between other members of the pantheon and human petitioners.

Pabilsaĝ was a Mesopotamian god. Not much is known about his role in Mesopotamian religion, though it is known that he could be regarded as a bow-armed warrior deity, as a divine cadastral officer or a judge. He might have also been linked to healing, though this remains disputed. In his astral aspect, first attested in the Old Babylonian period, he was a divine representation of the constellation Sagittarius.

Ninazu was a Mesopotamian god of the underworld. He was also associated with snakes and vegetation, and with time acquired the character of a warrior god. He was frequently associated with Ereshkigal, either as a son, husband, or simply a member the same category of underworld deities.

Ḫegir (𒀭𒃶𒄈) or Ḫegirnunna (𒀭𒃶𒄈𒉣𒈾) was a Mesopotamian goddess who belonged to the pantheon of Lagash. She was considered a daughter of Bau and Ningirsu.

Gatumdug was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the tutelary deity of Lagash and closely associated with its kings. She was initially worshiped only in this city and in NINA, but during the reign of Gudea a temple was built for her in Girsu. She appears in a number of literary compositions, including the hymn inscribed on the Gudea cylinders and Lament for Sumer and Ur.

Nindara was a Mesopotamian god worshiped in the state of Lagash. He was the husband of Nanshe, and it is assumed that his relevance in Mesopotamian religion depended on this connection. His character remains opaque due to his small role in known texts.

Nindub or Ninduba was a Mesopotamian god associated with exorcisms. He is attested chiefly in sources from the state of Lagash, including Early Dynastic offering lists and the cylinders of Gudea. He continued to be worshiped in this area in the Ur III period. However, in the Old Babylonian period he appears only in a small number of god lists presumed to reflect archaic tradition.

Shulshaga (Šulšaga) or Shulsagana (Šulšagana) was a Mesopotamian god. He was a part of the state pantheon of the city-state of Lagash. His name means "youth of his heart" in Sumerian, with the possessive pronoun possibly referring to Shulshaga's father, Ningirsu.

Geshtinanna was a Mesopotamian goddess best known due to her role in myths about the death of Dumuzi, her brother. It is not certain what functions she fulfilled in the Mesopotamian pantheon, though her association with the scribal arts and dream interpretation is well attested. She could serve as a scribe in the underworld, where according to the myth Inanna's Descent she had to reside for a half of each year in place of her brother.

The E-ninnu 𒂍𒐐 was the E (temple) to the warrior god Ningirsu in the Sumerian city of Girsu in southern Mesopotamia. Girsu was the religious centre of a state that was named Lagash after its most populous city, which lay 25 km southeast of Girsu. Rulers of Lagash who contributed to the structure of the E-ninnu included Ur-Nanshe of Lagash in the late 26th century BC, his grandson Eannatum in the following century, Urukagina in the 24th century and Gudea, ruler of Lagash in the mid 22nd century BC.

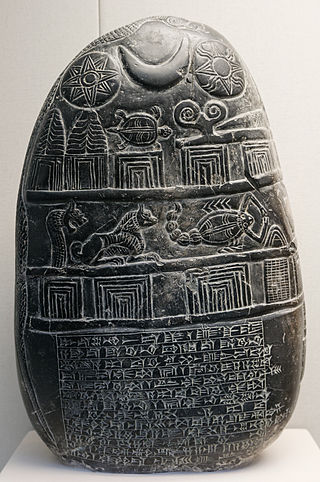

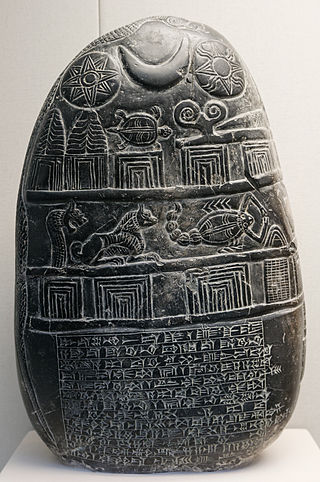

The Gudea cylinders are a pair of terracotta cylinders dating to c. 2125 BC, on which is written in cuneiform a Sumerian myth called the Building of Ningirsu's temple. The cylinders were made by Gudea, the ruler of Lagash, and were found in 1877 during excavations at Telloh, Iraq and are now displayed in the Louvre in Paris, France. They are the largest cuneiform cylinders yet discovered and contain the longest known text written in the Sumerian language.

Dumuzi-abzu, sometimes spelled Dumuziabzu, was a Mesopotamian goddess worshiped in the state of Lagash. She was the tutelary deity of Kinunir.

Nin-MAR.KI was a Mesopotamian goddess. The reading and meaning of her name remain uncertain, though options such as Ninmar and Ninmarki can be found in literature. In the past the form Ninkimar was also in use. She was considered the divine protector of cattle, and additionally functioned as an oath deity. She might have been associated with long distance trade as well. It is possible that in art she was depicted in the company of birds, similar to her mother Nanshe. Other deities associated with her include other members of the pantheon Lagash, such as Dumuzi-abzu and Hendursaga.

Enegi or Enegir was an ancient Mesopotamian city located in present-day Iraq. It is considered lost, though it is known that it was one of the settlements in the southernmost part of lower Mesopotamia, like Larsa, Ur and Eridu. Attempts have been made to identify it with multiple excavated sites. In textual sources, it is well documented as the cult center of the god Ninazu, and in that capacity it was connected to beliefs tied to the underworld. It appears in sources from between the Early Dynastic and Old Babylonian periods. Later on the cult of its tutelary god might have been transferred to Ur.