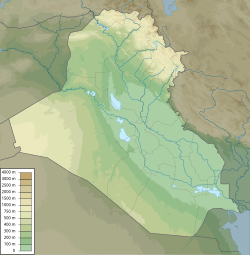

Ur was an important Sumerian city-state in ancient Mesopotamia, located at the site of modern Tell el-Muqayyar in Dhi Qar Governorate, southern Iraq. Although Ur was once a coastal city near the mouth of the Euphrates on the Persian Gulf, the coastline has shifted and the city is now well inland, on the south bank of the Euphrates, 16 km (10 mi) from Nasiriyah in modern-day Iraq. The city dates from the Ubaid period c. 3800 BC, and is recorded in written history as a city-state from the 26th century BC, its first recorded king being King Tuttues.

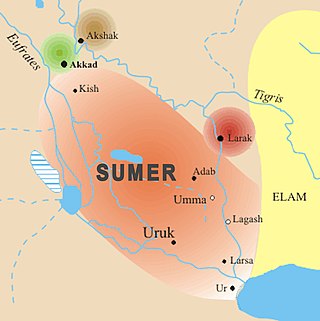

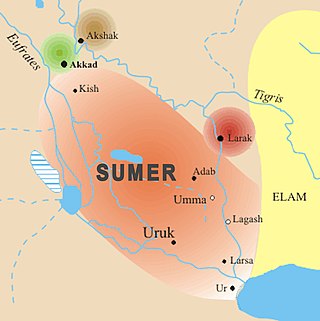

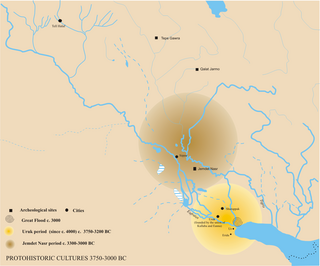

The history of Sumer spans the 5th to 3rd millennia BCE in southern Mesopotamia, and is taken to include the prehistoric Ubaid and Uruk periods. Sumer was the region's earliest known civilization and ended with the downfall of the Third Dynasty of Ur around 2004 BCE. It was followed by a transitional period of Amorite states before the rise of Babylonia in the 18th century BCE.

Uruk, known today as Warka, was an ancient city in the Near East, located east of the current bed of the Euphrates River, on an ancient, now-dried channel of the river. The site lies 93 kilometers northwest of ancient Ur, 108 kilometers southeast of ancient Nippur, and 24 kilometers southeast of ancient Larsa. It is 30 km (19 mi) east of modern Samawah, Al-Muthannā, Iraq.

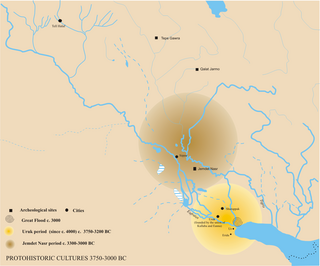

Nippur was an ancient Sumerian city. It was the special seat of the worship of the Sumerian god Enlil, the "Lord Wind", ruler of the cosmos, subject to An alone. Nippur was located in modern Nuffar 5 miles north of modern Afak, Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq. It is roughly 200 kilometers south of modern Baghdad and about 96.54 km southeast of the ancient city of Babylon. Occupation at the site extended back to the Ubaid period, the Uruk period, and the Jemdet Nasr period. The origin of the ancient name is unknown but different proposals have been made.

Ziusudra of Shuruppak is listed in the WB-62 Sumerian King List recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the Great Flood. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the Eridu Genesis and appears in the writings of Berossus as Xisuthros.

Lagash was an ancient city-state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about 22 kilometres (14 mi) east of the modern town of Al-Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash was one of the oldest cities of the Ancient Near East. The ancient site of Nina is around 10 km (6.2 mi) away and marks the southern limit of the state. Nearby Girsu, about 25 km (16 mi) northwest of Lagash, was the religious center of the Lagash state. The Lagash state's main temple was the E-ninnu at Girsu, dedicated to the god Ningirsu. The Lagash state incorporated the ancient cities of Lagash, Girsu, Nina.

Umma (Sumerian: 𒄑𒆵𒆠ummaKI; in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell Jokha. More recently it has been suggested that it was located at Umm al-Aqarib, less than 7 km to its northwest or was even the name of both cities. One or both were the leading city of the Early Dynastic kingdom of Gišša, with the most recent excavators putting forth that Umm al-Aqarib was prominent in EDIII but Jokha rose to preeminence later. The town of KI.AN was also nearby. KI.AN, which was destroyed by Rimush, a ruler of the Akkadian Empire. There are known to have been six gods of KI.AN including Gula KI.AN and Sara KI.AN.

Isin (Sumerian: 𒉌𒋛𒅔𒆠, romanized: I3-si-inki, modern Arabic: Ishan al-Bahriyat) is an archaeological site in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq which was the location of the Ancient Near East city of Isin, occupied from the late 4th millennium Uruk period up until at least the late 1st millennium BC Neo-Babylonian period. It lies about 40 km (25 mi) southeast of the modern city of Al Diwaniyah.

Aššur (; Sumerian: 𒀭𒊹𒆠 AN.ŠAR2KI, Assyrian cuneiform: Aš-šurKI, "City of God Aššur"; Syriac: ܐܫܘܪ Āšūr; Old Persian: 𐎠𐎰𐎢𐎼 Aθur, Persian: آشور Āšūr; Hebrew: אַשּׁוּר ʾAššūr, Arabic: اشور), also known as Ashur and Qal'at Sherqat, was the capital of the Old Assyrian city-state (2025–1364 BC), the Middle Assyrian Empire (1363–912 BC), and for a time, of the Neo-Assyrian Empire (911–609 BC). The remains of the city lie on the western bank of the Tigris River, north of the confluence with its tributary, the Little Zab, in what is now Iraq, more precisely in the al-Shirqat District of the Saladin Governorate.

Adab was an ancient Sumerian city between Girsu and Nippur, lying about 35 kilometers southeast of the latter. It was located at the site of modern Bismaya or Bismya in the Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate of Iraq. The site was occupied at least as early as the 3rd Millenium BC, through the Early Dynastic, Akkadian Empire, and Ur III empire periods, into the Kassite period in the mid-2nd millennium BC. It is known that there were temples of Ninhursag/Digirmah, Iskur, Asgi, Inanna and Enki at Adab and that the city-god of Adab was Parag'ellilegarra (Panigingarra) "The Sovereign Appointed by Ellil".

Jemdet Nasr is a tell or settlement mound in Babil Governorate (Iraq) that is best known as the eponymous type site for the Jemdet Nasr period, and was one of the oldest Sumerian cities. It is adjacent to the much larger site of Tell Barguthiat. The site was first excavated in 1926 by Stephen Langdon, who found Proto-Cuneiform clay tablets in a large mudbrick building thought to be the ancient administrative centre of the site. A second season took place in 1928, but this season was very poorly recorded. Subsequent excavations in the 1980s under British archaeologist Roger Matthews were, among other things, undertaken to relocate the building excavated by Langdon. These excavations have shown that the site was also occupied during the Ubaid, Uruk and Early Dynastic I periods. Based on texts found there mentioning an ensi of NI.RU that is thought to be its ancient name. During ancient times the city was on a canal linking it to other major Sumerian centers.

The Early Dynastic period is an archaeological culture in Mesopotamia that is generally dated to c. 2900 – c. 2350 BC and was preceded by the Uruk and Jemdet Nasr periods. It saw the development of writing and the formation of the first cities and states. The ED itself was characterized by the existence of multiple city-states: small states with a relatively simple structure that developed and solidified over time. This development ultimately led to the unification of much of Mesopotamia under the rule of Sargon, the first monarch of the Akkadian Empire. Despite this political fragmentation, the ED city-states shared a relatively homogeneous material culture. Sumerian cities such as Uruk, Ur, Lagash, Umma, and Nippur located in Lower Mesopotamia were very powerful and influential. To the north and west stretched states centered on cities such as Kish, Mari, Nagar, and Ebla.

Marad was an ancient Near Eastern city. Marad was situated on the west bank of the then western branch of the Upper Euphrates River west of Nippur in modern-day Iraq and roughly 50 km southeast of Kish, on the Arahtu River. The site was identified in 1912 based on a Neo-Babylonian inscription on a truncated cylinder of Nebuchadrezzar noting the restoration of the temple. The cylinder was not excavated but rather found by locals so its provenance was not certain, as to some extent was the site's identification as Marad. In ancient times it was on the canal, Abgal, running between Babylon and Isin.

Kisurra was an ancient Sumerian tell situated on the west bank of the Euphrates, 7 kilometres (4.3 mi) north of Shuruppak and due east of Kish.

The Jemdet Nasr Period is an archaeological culture in southern Mesopotamia. It is generally dated from 3100 to 2900 BC. It is named after the type site Tell Jemdet Nasr, where the assemblage typical for this period was first recognized. Its geographical distribution is limited to south-central Iraq. The culture of the proto-historical Jemdet Nasr period is a local development out of the preceding Uruk period and continues into the Early Dynastic I period.

The archaeological site of Abu Salabikh, around 20 km (12 mi) northwest of the site of ancient Nippur and about 150 kilometers southeast of the modern city of Baghdad in Al-Qādisiyyah Governorate, Iraq marks the site of a small Sumerian city that existed from the Neolithic through the late 3rd millennium, with cultural connections to the cities of Kish, Mari and Ebla. Its ancient name is unknown though Eresh and Kesh have been suggested as well as Gišgi. Kesh was suggested by Thorkild Jacobsen before excavations began. The Euphrates was the city's highway and lifeline; when it shifted its old bed, in the late third millennium BC, the city dwindled away. Only eroded traces remain on the site's surface of habitation after the Early Dynastic Period. There is another small archaeological site named Abu-Salabikh in the Hammar Lake region of Southern Iraq, which has been suggested as the possible capital of the Sealand dynasty.

Tell Uqair is a tell or settlement mound northeast of ancient Babylon, about 25 kilometers north-northeast of the ancient city of Kish, just north of Kutha, and about 50 miles (80 km) south of Baghdad in modern Babil Governorate, Iraq. It was occupied in the Ubaid period and the Uruk period. It has been proposed as the site of the 3rd millennium BC city of Urum.

Tell Khaiber is a tell, or archaeological settlement mound, in southern Mesopotamia. It is located thirteen kilometers west of the modern city of Nasiriyah, about 19 kilometers northwest of the ancient city of Ur in Dhiq Qar Province and 25 kilometers south of the ancient city of Larsa. In 2012, the site was visited by members of the Ur Region Archaeology Project (URAP), a cooperation between the British Institute for the Study of Iraq, the University of Manchester and the Iraqi State Board for Antiquities and Heritage. They found that the site had escaped looting, and applied for an excavation permit.

Tell Zurghul, also spelled Tell Surghul, is an archaeological site in Dhi Qar Governorate (Iraq). It lies on an ancient canal leading from Lagash of which is lies 10 km to the south-east. Its ancient name was the cuneiform read as Niĝin. The city god was Nanshe (Nanše), who had temples there (E-sirara) and at nearby Girsu. She was the daughter of Enki and sister of Ningirsu and Nisaba. Niĝin, along with the cities of Girsu and Lagash, was part of the State of Lagash in the later part of the 3rd Millennium BC.

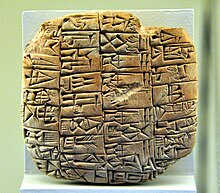

The proto-cuneiform script was a system of proto-writing that emerged in Mesopotamia, eventually developing into the early cuneiform script used in the region's Early Dynastic I period. It arose from the token-based system that had already been in use across the region in preceding millennia. While it is known definitively that later cuneiform was used to write the Sumerian language, it is still uncertain what the underlying language of proto-cuneiform texts was.