Enlil, later known as Elil, is an ancient Mesopotamian god associated with wind, air, earth, and storms. He is first attested as the chief deity of the Sumerian pantheon, but he was later worshipped by the Akkadians, Babylonians, Assyrians, and Hurrians. Enlil's primary center of worship was the Ekur temple in the city of Nippur, which was believed to have been built by Enlil himself and was regarded as the "mooring-rope" of heaven and earth. He is also sometimes referred to in Sumerian texts as Nunamnir. According to one Sumerian hymn, Enlil himself was so holy that not even the other gods could look upon him. Enlil rose to prominence during the twenty-fourth century BC with the rise of Nippur. His cult fell into decline after Nippur was sacked by the Elamites in 1230 BC and he was eventually supplanted as the chief god of the Mesopotamian pantheon by the Babylonian national god Marduk.

Gilgamesh was a hero in ancient Mesopotamian mythology and the protagonist of the Epic of Gilgamesh, an epic poem written in Akkadian during the late 2nd millennium BC. He was possibly a historical king of the Sumerian city-state of Uruk, who was posthumously deified. His rule probably would have taken place sometime in the beginning of the Early Dynastic Period, c. 2900 – 2350 BC, though he became a major figure in Sumerian legend during the Third Dynasty of Ur.

Noah appears as the last of the Antediluvian patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible, the Quran and Baha'i writings. Noah is referenced in various other books of the Bible, including the New Testament, and in associated deuterocanonical books.

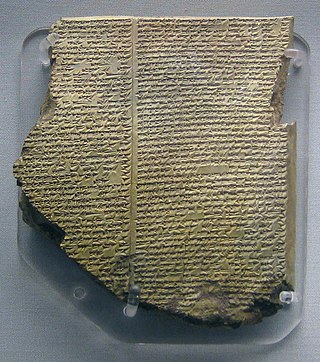

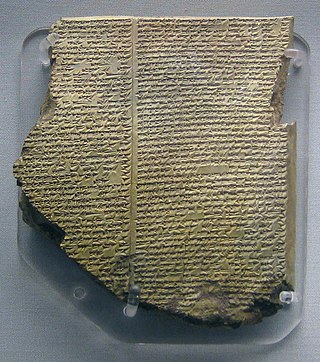

The Epic of Gilgamesh is an epic poem from ancient Mesopotamia. The literary history of Gilgamesh begins with five Sumerian poems about Gilgamesh, king of Uruk, some of which may date back to the Third Dynasty of Ur. These independent stories were later used as source material for a combined epic in Akkadian. The first surviving version of this combined epic, known as the "Old Babylonian" version, dates back to the 18th century BC and is titled after its incipit, Shūtur eli sharrī. Only a few tablets of it have survived. The later Standard Babylonian version compiled by Sîn-lēqi-unninni dates to somewhere between the 13th to the 10th centuries BC and bears the incipit Sha naqba īmuru. Approximately two-thirds of this longer, twelve-tablet version have been recovered. Some of the best copies were discovered in the library ruins of the 7th-century BC Assyrian king Ashurbanipal.

Noah's Ark is the ship in the Genesis flood narrative through which God spares Noah, his family, and examples of all the world's animals from a global deluge. The story in Genesis is based on earlier flood myths originating in Mesopotamia, and is repeated, with variations, in the Quran, where the Ark appears as Safinat Nūḥ and al-fulk. The myth of the global flood that destroys all life begins to appear in the Old Babylonian Empire period. The version closest to the biblical story of Noah, as well as its most likely source, is that of Utnapishtim in the Epic of Gilgamesh.

Ziusudra of Shuruppak is listed in the WB-62 Sumerian King List recension as the last king of Sumer prior to the Great Flood. He is subsequently recorded as the hero of the Sumerian creation myth and appears in the writings of Berossus as Xisuthros.

The Anunnaki are a group of deities of the ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians. In the earliest Sumerian writings about them, which come from the Post-Akkadian period, the Anunnaki are deities in the pantheon, descendants of An and Ki, the god of the heavens and the goddess of earth, and their primary function was to decree the fates of humanity. They should not be confused with the Apkallu.

A flood myth or a deluge myth is a myth in which a great flood, usually sent by a deity or deities, destroys civilization, often in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primaeval waters which appear in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who "represents the human craving for life".

Atra-Hasis is an 18th-century BC Akkadian epic, recorded in various versions on clay tablets, named for its protagonist, Atrahasis. The Atra-Hasis tablets include both a creation myth and one of three surviving Babylonian flood myths. The name "Atra-Hasis" also appears, as king of Shuruppak in the times before a flood, on one of the Sumerian King Lists.

Siduri, or more accurately Šiduri, is a character in the Epic of Gilgamesh. She is described as an alewife. The oldest preserved version of the composition to contain the episode involving her leaves her nameless, and in the later standard edition compiled by Sîn-lēqi-unninni her name only appears in a single line. She is named Naḫmazulel or Naḫmizulen in the preserved fragments of Hurrian and Hittite translations. It has been proposed that her name in the standard edition is derived from an epithet applied to her by the Hurrian translator, šiduri, "young woman." An alternate proposal instead connects it with the Akkadian personal name Šī-dūrī, "she is my protection." In all versions of the myth in which she appears, she offers advice to the hero, but the exact contents of the passage vary. Possible existence of Biblical and Greek reflections of the Šiduri passage is a subject of scholarly debate.

Mount Nisir, mentioned in the ancient Mesopotamian Epic of Gilgamesh, is supposedly the mountain known today as Pir Omar Gudrun, near the city Sulaymaniyah in Iraqi Kurdistan. The name may mean "Mount of Salvation".

The Gilgamesh flood myth is a flood myth in the Epic of Gilgamesh. It is one of three Mesopotamian Flood Myths: the Sumerian Flood Story, an episode of the Atra-Hasis Epic and included in the Epic of Gilgamesh. Many scholars believe that the flood myth was added to Tablet XI in the "standard version" of the Gilgamesh Epic by an editor who used the flood story from the Epic of Atra-Hasis. A short reference to the flood myth is also present in the much older Sumerian Gilgamesh poems, from which the later Babylonian versions drew much of their inspiration and subject matter.

Ilawela is, in Sumerian and Akkadian mythology, a minor god of intelligence. In the Atra-Hasis Epic he was sacrificed by the great gods and his blood was used in the creation of mankind:

Ilawela who had intelligence,

They slaughtered in their assembly.

Nintu mixed clay

With his flesh and blood.

They heard the drumbeat forever after.

A ghost came into existence from the god’s flesh,

And she (Nintu) proclaimed it as his living sign.

The ghost existed so as not to forget. […]

You have slaughtered a god together with his intelligence.

I have relieved you of your hard work.

I have imposed your load on man.

Ubara-tutu of Shuruppak was the last antediluvian king of Sumer, according to some versions of the Sumerian King List. He was said to have reigned for 18,600 years. He was the son of En-men-dur-ana, a Sumerian mythological figure often compared to Enoch, as he entered heaven without dying. Ubara-Tutu was the king of Sumer until a flood swept over his land.

Sumerian literature constitutes the earliest known corpus of recorded literature, including the religious writings and other traditional stories maintained by the Sumerian civilization and largely preserved by the later Akkadian and Babylonian empires. These records were written in the Sumerian language in the 18th and 17th centuries BC during the Middle Bronze Age.

The earliest record of a Sumerian creation myth, called The Eridu Genesis by historian Thorkild Jacobsen, is found on a single fragmentary tablet excavated in Nippur by the Expedition of the University of Pennsylvania in 1893, and first recognized by Arno Poebel in 1912. It is written in the Sumerian language and dated to around 1600 BC. Other Sumerian creation myths from around this date are called the Barton Cylinder, the Debate between sheep and grain and the Debate between Winter and Summer, also found at Nippur.

The Instructions of Shuruppak are a significant example of Sumerian wisdom literature. Wisdom literature, intended to teach proper piety, inculcate virtue, and preserve community standards, was common throughout the ancient Near East. Its incipit sets the text in great antiquity by : "In those days, in those far remote times, in those nights, in those faraway nights, in those years, in those far remote years." The precepts are placed in the mouth of a king Šuruppak (SU.KUR.RUki), son of Ubara-Tutu. Ubara-Tutu is recorded in most extant copies of the Sumerian king list as being the final king of Sumer prior to the deluge. Ubara-tutu is briefly mentioned in tablet XI of the Epic of Gilgamesh, where he is identified as the father of Utnapishtim, a character who is instructed by the god Ea to build a boat in order to survive the coming flood. Grouped with the other cuneiform tablets from Abu Salabikh, the Instructions date to the early third millennium BCE, being among the oldest surviving literature.

Mesopotamian mythology refers to the myths, religious texts, and other literature that comes from the region of ancient Mesopotamia which is a historical region of Western Asia, situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system that occupies the area of present-day Iraq. In particular the societies of Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria, all of which existed shortly after 3000 BCE and were mostly gone by 400 CE. These works were primarily preserved on stone or clay tablets and were written in cuneiform by scribes. Several lengthy pieces have survived erosion and time, some of which are considered the oldest stories in the world, and have given historians insight into Mesopotamian ideology and cosmology.

Erragal or Errakal was a Mesopotamian god presumed to be related to Erra. However, there is no agreement about the nature of the connection between them in Assyriology. While Erragal might have been associated with storms and the destruction caused by them, he is chiefly attested as a benevolent deity, for example as an astral god with apotropaic functions. He was regarded as the husband of the goddess Ninšar, the divine butcher of Ekur, and they could be represented as a pair of stars in astronomical treatises such as MUL.APIN. References to worship of Erragal are uncommon, though he nonetheless appears in a variety of sources from the Isin-Larsa period to Neo-Babylonian times. He also appears in the Epic of Gilgamesh and in Atra-Hasis as a deity linked to the great flood.

A one-third scale replica of a Babylonian "ark" was constructed in 2014 based on recently discovered tablets from the Epic of Gilgamesh.