African immigrants in Europe are individuals residing in Europe who were born in Africa. This includes both individuals born in North Africa and Sub-Saharan Africa.

Illegal immigration is the migration of people into a country in violation of that country's immigration laws, or the continuous residence in a country without the legal right to. Illegal immigration tends to be financially upward, from poorer to richer countries. Illegal residence in another country creates the risk of detention, deportation, and/or other persecutions.

African Australians are Australians descended from the any peoples of Sub-Saharan Africa, including naturalised Australians who are immigrants from various regions in Sub-Saharan Africa and descendants of such immigrants. At the 2021 census, the number of ancestry responses categorised within Sub-Saharan African ancestral groups as a proportion of the total population amounted to 1.3%.

Immigration to Greece percentage of foreign populations in Greece is 7.1% in proportion to the total population of the country. Moreover, between 9 and 11% of the registered Greek labor force of 4.4 million are foreigners. Migrants additionally make up 25% of wage and salary earners.

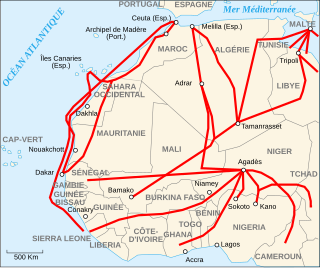

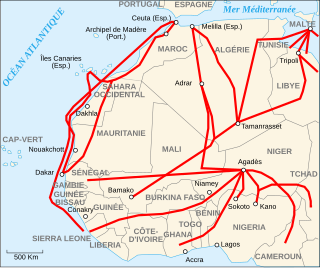

Migrants' routes encompass the primary geographical routes from tropical Africa to Europe, which individuals undertake in search of residence and employment opportunities not available in their home countries. While Europe remains the predominant destination for most migrants, alternative routes also direct migrants towards South Africa and Asia. The routes are monitored by, among others, the Spanish NGO Caminando Fronteras / Walking Borders, the European group InfoMigrants and the United Nations

Immigration to Europe has a long history, but increased substantially after World War II. Western European countries, especially, saw high growth in immigration post 1945, and many European nations today have sizeable immigrant populations, both of European and non-European origin. In contemporary globalization, migrations to Europe have accelerated in speed and scale. Over the last decades, there has been an increase in negative attitudes towards immigration, and many studies have emphasized marked differences in the strength of anti-immigrant attitudes among European countries.

In 2021, Istat estimated that 5,171,894 foreign citizens lived in Italy, representing about 8.7% of the total population. 98 to 99 percent more of Italy's full population is (caucasioid) as 2024. These figures include naturalized foreign-born residents as well as illegal immigrants, the so-called clandestini, whose numbers, difficult to determine, are thought to be at least 670,000.

South Africa experiences a relatively high influx of immigration annually. As of 2019, the amount of immigrants entering the country continues to increase, the majority of whom are working residents and hold great influence influence over the continued presence of several sectors throughout South Africa. The demographic background of these migrant groups is very diverse, with many of the countries of origin belonging to nations throughout sub-saharan Africa. A portion of them have qualified as refugees since the 1990s.

Libya is a transit and destination country for men and women from sub-Saharan Africa and Asia trafficked for the purposes of forced labor and commercial sexual exploitation. While most foreigners in Libya are economic migrants, in some cases large smuggling debts of $500–$2,000 and illegal status leave them vulnerable to various forms of coercion, resulting in cases of forced prostitution and forced labor.

Immigration to Pakistan is the legal entry and settlement of foreign nationals in Pakistan. Immigration policy is overseen by the Interior Minister of Pakistan through the Directorate General Passports. Most immigrants are not eligible for citizenship or permanent residency, unless they are married to a Pakistani citizen or a Commonwealth citizen who has invested a minimum of PKR 5 million in the local economy.

African immigration to Israel is the international movement to Israel from Africa of people that are not natives or do not possess Israeli citizenship in order to settle or reside there. This phenomenon began in the second half of the 2000s, when a large number of people from Africa entered Israel, mainly through the then-lightly fenced border between Israel and Egypt in the Sinai Peninsula. According to the data of the Israeli Interior Ministry, 26,635 people arrived illegally in this way by July 2010, and over 55,000 by January 2012. In an attempt to curb the influx, Israel constructed the Egypt–Israel barrier. Since its completion in December 2013, the barrier has almost completely stopped the immigration of Africans into Israel across the Sinai border.

During the period of 1965 – 2021, an estimated 440,000 people per year emigrated from Africa; a total number of 17 million migrants within Africa was estimated for 2005. The figure of 0.44 million African emigrants per year pales in comparison to the annual population growth of about 2.6%, indicating that only about 2% of Africa's population growth is compensated for by emigration.

The Lampedusa immigrant reception center, officially Reception Center (CDA) of Lampedusa, has been operating since 1998, when the Italian island of Lampedusa became a primary European entry point for immigrants from Africa. It is one of a number of centri di accoglienza (CDA) maintained by the Italian government. The reception center's capacity of 801 people has been greatly exceeded by numerous people arriving on boats from various parts of Africa.

Illegal immigration in Mexico has occurred at various times throughout history, especially in the 1830s and since the 1970s. The largest source of illegal immigrants in Mexico are the impoverished Central American countries of Guatemala, Haiti, Honduras, and El Salvador and African countries like Democratic Republic of Congo, Cameroon, Guinea, Ghana and Nigeria. The largest single group of illegal immigrants in Mexico is from the United States.

The Ghana Immigration Service (GIS) is in charge of the removal and deportation of illegal immigrants in Ghana.

Prostitution in Libya is illegal, but common. Since the country's Cultural Revolution in 1973, laws based on Sharia law's zina are used against prostitutes; the punishment can be 100 lashes. Exploitation of prostitutes, living off the earnings of prostitution or being involved in the running of brothels is outlawed by Article 417 of the Libyan Penal Code. Buying sexual services isn't prohibited by law, but may contravene Sharia law.

This article delineates the issue of immigration in different countries.

Voluntary return or voluntary repatriation is usually the return of an illegal immigrant or over-stayer, a rejected asylum seeker, a refugee or displaced person, or an unaccompanied minor; sometimes it is the emigration of a second-generation immigrant who makes an autonomous decision to return to their ethnic homeland when they are unable or unwilling to remain in the host country.

Immigration to Malta has increased significantly over the past decade. In 2011, immigration contributed to 4.9% of the total population of the Maltese islands in 2011, i.e. 20,289 persons of non-Maltese citizenship, of whom 643 were born in Malta. In 2011, most of migrants in Malta were EU citizens, predominantly from the United Kingdom.

Externalization describes the efforts of wealthy, developed countries to prevent asylum seekers and other migrants from reaching their borders, often by enlisting third countries or private entities. Externalization is used by Australia, Canada, the United States, the European Union and the United Kingdom. Although less visible than physical barriers at international borders, externalization controls or restricts mobility in ways that are out of sight and far from the country's border. Examples include visa restrictions, sanctions for carriers that transport asylum seekers, and agreements with source and transit countries. Consequences often include increased irregular migration, human smuggling, and border deaths.