Related Research Articles

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Abu was a Mesopotamian god. His character is poorly understood, though it is assumed he might have been associated with vegetation and with snakes. He was often paired with the deity Gu2-la2, initially regarded as distinct from Gula, but later conflated with her.

Aya was a Mesopotamian goddess associated with dawn. Multiple variant names were attributed to her in god lists. She was regarded as the wife of Shamash, the sun god. She was worshiped alongside her husband in Sippar. Multiple royal inscriptions pertaining to this city mention her. She was also associated with the Nadītu community inhabiting it. She is less well attested in the other cult center of Shamash, Larsa, though she was venerated there as well. Additional attestations are available from Uruk, Mari and Assur. Aya was also incorporated into Hurrian religion, and in this context she appears as the wife of Shamash's counterpart Šimige.

Kakka was a Mesopotamian god best known as the sukkal of Anu and Anshar. His cult center was Maškan-šarrum, most likely located in the north of modern Iraq on the banks of the Tigris.

Numushda was a Mesopotamian god best known as the tutelary deity of Kazallu. The origin of his name is unknown, and might be neither Sumerian nor Akkadian. He was regarded as a violent deity, and was linked with nature, especially with flooding. A star named after him is also attested. He was regarded as a son of Nanna and Ningal, or alternatively of Enki. His wife was the sparsely attested goddess Namrat. According to the myth The Marriage of Martu they had a daughter, Adgarkidu, who married the eponymous deity. Late sources associate Numushda with the weather god Ishkur.

Tilla or Tella was a Hurrian god assumed to have the form of a bull. He is best attested in texts from Nuzi, where he commonly appears in theophoric names. His main cult center was Ulamme.

Tishpak (Tišpak) was a Mesopotamian god associated with the ancient city Eshnunna and its sphere of influence, located in the Diyala area of Iraq. He was primarily a war deity, but he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mushussu and bashmu, and with kingship.

Ninkarrak was a goddess of medicine worshiped chiefly in northern Mesopotamia and Syria. It has been proposed that her name originates in either Akkadian or an unidentified substrate language possibly spoken in parts of modern Syria, rather than in Sumerian. It is presumed that inconsistent orthography reflects ancient scholarly attempts at making it more closely resemble Sumerian theonyms. The best attested temples dedicated to her existed in Sippar and in Terqa. Finds from excavations undertaken at the site of the latter were used as evidence in more precisely dating the history of the region. Further attestations are available from northern Mesopotamia, including the kingdom of Apum, Assyria, and the Diyala area, from various southern Mesopotamian cities such as Larsa, Nippur, and possibly Uruk, as well as from Ugarit and Emar. It is possible that references to "Ninkar" from the texts from Ebla and Nikarawa, attested in Luwian inscriptions from Carchemish, were about Ninkarrak.

Ninisina was a Mesopotamian goddess who served as the tutelary deity of the city of Isin. She was considered a healing deity. She was believed to be skilled in the medical arts, and could be described as a divine physician or midwife. As an extension of her medical role, she was also believed to be capable of expelling various demons. Her symbols included dogs, commonly associated with healing goddesses in Mesopotamia, as well as tools and garments associated with practitioners of medicine.

Shuzianna was a Mesopotamian goddess. She was chiefly worshiped in Nippur, where she was regarded as a secondary spouse of Enlil. She is also known from the enumerations of children of Enmesharra, while in the myth Enki and Ninmah she is one of the seven minor goddesses helping with the creation of mankind.

Sukkal was a term which could denote both a type of official and a class of deities in ancient Mesopotamia. The historical sukkals were responsible for overseeing the execution of various commands of the kings and acted as diplomatic envoys and translators for foreign dignitaries. The deities referred to as sukkals fulfilled a similar role in mythology, acting as servants, advisors and envoys of the main gods of the Mesopotamian pantheon, such as Enlil or Inanna. The best known sukkal is the goddess Ninshubur. In art, they were depicted carrying staves, most likely understood as their attribute. They could function as intercessory deities, believed to mediate between worshipers and the major gods.

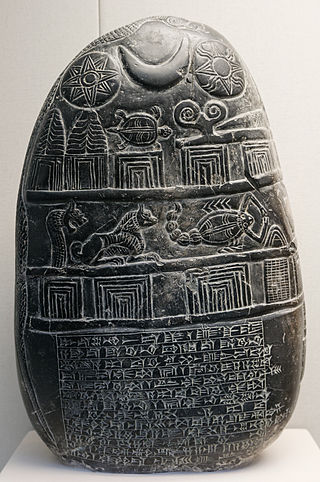

Gula was a Mesopotamian goddess of medicine, portrayed as a divine physician and midwife. Over the course of the second and first millennia BCE, she became one of the main deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon, and eventually started to be viewed as the second highest ranked goddess after Ishtar. She was associated with dogs, and could be depicted alongside these animals, for example on kudurru, and receive figurines representing them as votive offerings.

Ugur was a Mesopotamian god associated with war and death, originally regarded as an attendant deity (sukkal) of Nergal. After the Old Babylonian period he was replaced in this role by Ishum, and in the Middle Babylonian period his name started to function as a logogram representing Nergal. Temples dedicated to him existed in Isin and Girsu. He was also worshiped outside Mesopotamia by Hurrians and Hittites. He might also be attested in sources from Emar.

An = Anum, also known as the Great God List, is the longest preserved Mesopotamian god list, a type of lexical list cataloging the deities worshiped in the Ancient Near East, chiefly in modern Iraq. While god lists are already known from the Early Dynastic period, An = Anum most likely was composed in the later Kassite period.

Meme or Memešaga was a Mesopotamian goddess possibly regarded as a divine caretaker. While originally fully separate, she eventually came to be treated as one and the same as Gula, and as such came to be associated with medicine. The god list An = Anum additionally indicates she served as the sukkal of Ningal.

Lugal-Marada was a Mesopotamian god who served as the tutelary deity of the city of Marad. His wife was Imzuanna. He was seemingly conflated with another local god, Lulu. There is also evidence that he could be viewed as a manifestation of Ninurta. He had a temple in Marad, the Eigikalamma, and additionally appears in Old Babylonian oath formulas from this city.

Inanna of Zabalam was a hypostasis of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna associated with the city of Zabalam. It has been proposed that she was initially a separate deity, perhaps known under the name Nin-UM, who came to be absorbed by the goddess of Uruk at some point in the prehistory of Mesopotamia and lost her unknown original character in the process, though in certain contexts she nonetheless could still be treated as distinct. She was regarded as the mother of Shara, the god of Umma, a city located near Zabalam.

Mīšaru (Misharu), possibly also known as Ili-mīšar, was a Mesopotamian god regarded as the personification of justice, sometimes portrayed as a divine judge. He was regarded as a son of the weather god Adad and his wife Shala. He was often associated with other similar deities, such as Išartu or Kittu. He is first attested in sources from the Ur III period. In the Old Babylonian period, he was regarded as the tutelary deity of Dūr-Rīmuš, a city in the kingdom of Eshnunna. He was also worshiped in other parts of Mesopotamia, for example in Mari, Assur, Babylon, Sippar and in the land of Suhum. In the Seleucid period he was introduced to the pantheon of Uruk.

Saĝkud was a Mesopotamian god who might have been regarded as a divine tax collector. He belonged to the court of Anu, though an association between him and Ninurta is also attested. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period, and appears in a variety of theophoric names from sites such as Lagash and later on Sippar. In the first millennium BCE he was worshiped in Der and Bubê. In the past it was assumed that skwt ("Sakkuth") mentioned in the Book of Amos might be the same deity, but this conclusion is no longer accepted.

Weidner god list is the conventional name of one of the known ancient Mesopotamian lists of deities, originally compiled by ancient scribes in the late third millennium BCE, with the oldest known copy dated to the Ur III or Isin-Larsa period. Further examples have been found in many excavated Mesopotamian cities, and come from between the Old Babylonian period and the fourth century BCE. It is agreed the text serverd as an exercise for novice scribes, but the principles guiding the arrangement of the listed deities remain unknown. In later periods, philological research lead to creation of extended versions providing explanations of the names of individual deities.

References

- 1 2 Simons 2017, p. 89.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Cavigneaux & Krebernik 1998, p. 532.

- 1 2 3 4 Stol 1987, p. 148.

- ↑ Litke 1998, p. 170.

- 1 2 3 Shibata 2009, p. 36.

- 1 2 Sibbing-Plantholt 2022, p. 72.

- 1 2 3 4 Schwemer 2001, p. 505.

- 1 2 Litke 1998, p. 171.

- ↑ Lambert 1980, p. 52.

- 1 2 Focke 1999, p. 105.

- 1 2 Black 2006, p. 132.

- ↑ Black 2006, pp. 131–132.

- 1 2 3 Tugendhaft 2016, p. 179.

Bibliography

- Black, Jeremy A. (2006). The Literature of Ancient Sumer. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-929633-0 . Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- Cavigneaux, Antoine; Krebernik, Manfred (1998), "NIN-zuʾana", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-07-25

- Focke, Karen (1999). "Die Göttin Ninimma". Archiv für Orientforschung. Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO)/Institut für Orientalistik. 46/47: 92–110. ISSN 0066-6440. JSTOR 41668442 . Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- Lambert, Wilfred G. (1980), "Ili-mīšar", Reallexikon der Assyriologie, retrieved 2022-07-25

- Litke, Richard L. (1998). A reconstruction of the Assyro-Babylonian god lists, AN:dA-nu-um and AN:Anu šá Ameli (PDF). New Haven: Yale Babylonian Collection. ISBN 978-0-9667495-0-2. OCLC 470337605.

- Schwemer, Daniel (2001). Die Wettergottgestalten Mesopotamiens und Nordsyriens im Zeitalter der Keilschriftkulturen: Materialien und Studien nach den schriftlichen Quellen (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. ISBN 978-3-447-04456-1. OCLC 48145544.

- Shibata, Daisuke (2009). "An Old Babylonian Manuscript of the Weidner God List from Tell Taban". Iraq. British Institute for the Study of Iraq, Cambridge University Press. 71: 33–42. ISSN 0021-0889. JSTOR 20779001 . Retrieved 2022-07-25.

- Sibbing-Plantholt, Irene (2022). The Image of Mesopotamian Divine Healers. Healing Goddesses and the Legitimization of Professional Asûs in the Mesopotamian Medical Marketplace. Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-51241-2. OCLC 1312171937.

- Simons, Frank (2017). "A New Join to the Hurro-Akkadian Version of the Weidner God List from Emar (Msk 74.108a + Msk 74.158k)". Altorientalische Forschungen. De Gruyter. 44 (1). doi:10.1515/aofo-2017-0009. ISSN 2196-6761.

- Stol, Marten (1987), "Lugal-Marada", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-07-25

- Tugendhaft, Aaron (2016). "Gods on clay: Ancient Near Eastern scholarly practices and the history of religions". In Grafton, Anthony; Most, Glenn W. (eds.). Canonical Texts and Scholarly Practices. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9781316226728.009.