Poetry is a form of literary art that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, literal or surface-level meanings. Any particular instance of poetry is called a poem and is written by a poet. Poets use a variety of techniques called poetic devices, such as assonance, alliteration, euphony and cacophony, onomatopoeia, rhythm, and sound symbolism, to produce musical or incantatory effects. Most poems are formatted in verse: a series or stack of lines on a page, which follow a rhythmic or other deliberate pattern. For this reason, verse has also become a synonym for poetry.

Wystan Hugh Auden was a British-American poet. Auden's poetry is noted for its stylistic and technical achievement, its engagement with politics, morals, love, and religion, and its variety in tone, form, and content. Some of his best known poems are about love, such as "Funeral Blues"; on political and social themes, such as "September 1, 1939" and "The Shield of Achilles"; on cultural and psychological themes, such as The Age of Anxiety; and on religious themes, such as "For the Time Being" and "Horae Canonicae".

Poetry analysis is the process of investigating the form of a poem, content, structural semiotics, and history in an informed way, with the aim of heightening one's own and others' understanding and appreciation of the work.

In prosody, alliterative verse is a form of verse that uses alliteration as the principal device to indicate the underlying metrical structure, as opposed to other devices such as rhyme. The most commonly studied traditions of alliterative verse are those found in the oldest literature of the Germanic languages, where scholars use the term 'alliterative poetry' rather broadly to indicate a tradition which not only shares alliteration as its primary ornament but also certain metrical characteristics. The Old English epic Beowulf, as well as most other Old English poetry, the Old High German Muspilli, the Old Saxon Heliand, the Old Norse Poetic Edda, and many Middle English poems such as Piers Plowman, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Layamon's Brut and the Alliterative Morte Arthur all use alliterative verse.

Chester Simon Kallman was an American poet, librettist, and translator, best known for collaborating with W. H. Auden on opera librettos for Igor Stravinsky and other composers.

"Musée des Beaux Arts" is a 23-line poem written by W. H. Auden in December 1938 while he was staying in Brussels, Belgium, with Christopher Isherwood. It was first published under the title "Palais des beaux arts" in the Spring 1939 issue of New Writing, a modernist magazine edited by John Lehmann. It next appeared in the collected volume of verse Another Time, which was followed four months later by the English edition. The poem's title derives from the Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique, the French-language name for the Royal Museums of Fine Arts of Belgium located in Brussels. The museum is famous for its collection of Early Netherlandish painting. When Auden visited the museum he would have seen a number of the paintings of the "Old Masters" referred to in the second line of the poem, including the Fall of Icarus which at the time was still regarded as an original by Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

This glossary of literary terms is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in the discussion, classification, analysis, and criticism of all types of literature, such as poetry, novels, and picture books, as well as of grammar, syntax, and language techniques. For a more complete glossary of terms relating to poetry in particular, see Glossary of poetry terms.

"September 1, 1939" is a poem by W. H. Auden written shortly after the German invasion of Poland, which would mark the start of World War II. It was first published in The New Republic issue of 18 October 1939, and in book form in Auden's collection Another Time (1940).

"Funeral Blues", or "Stop all the clocks", is a poem by W. H. Auden which first appeared in the 1936 play The Ascent of F6. Auden substantially rewrote the poem several years later as a cabaret song for the singer Hedli Anderson. Both versions were set to music by the composer Benjamin Britten. The second version was first published in 1938 and was titled "Funeral Blues" in Auden's 1940 Another Time. The poem experienced renewed popularity after being read in the film Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), which also led to increased attention on Auden's other work. It has since been cited as one of the most popular modern poems in the United Kingdom.

The Duino Elegies are a collection of ten elegies written by the Bohemian-Austrian poet Rainer Maria Rilke. He was then "widely recognized as one of the most lyrically intense German-language poets", and began the elegies in 1912 while a guest of Princess Marie von Thurn und Taxis at Duino Castle, on the Adriatic Sea. The poems were dedicated to the Princess upon their publication in 1923. During this ten-year period, the elegies languished incomplete for long stretches of time as Rilke had frequent bouts with severe depression—some of which were related to the events of World War I and being conscripted into military service. Aside from brief periods of writing in 1913 and 1915, he did not return to the work until a few years after the war ended. With a sudden, renewed burst of frantic writing which he described as a "boundless storm, a hurricane of the spirit"—he completed the collection in February 1922 while staying at Château de Muzot in Veyras, Switzerland. After their publication in 1923, the Duino Elegies were soon recognized as his most important work.

Letters from Iceland is a travel book in prose and verse by W. H. Auden and Louis MacNeice, published in 1937.

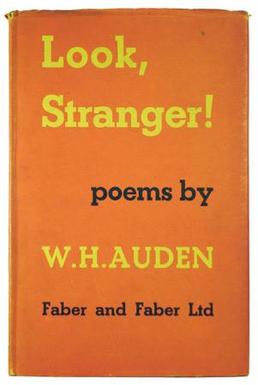

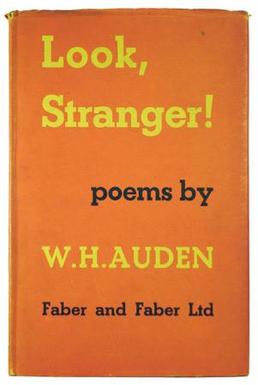

On This Island is a book of poems by W. H. Auden, first published under the title Look, Stranger! in the UK in 1936, then published under Auden's preferred title, On this Island, in the US in 1937. It is also the title of one of the poems in the collection.

"The Sea and the Mirror: A Commentary on Shakespeare's The Tempest" is a long poem by W. H. Auden, written 1942–44, and first published in 1944. Auden regarded the work as "my Ars Poetica, in the same way I believe The Tempest to have been Shakespeare's."

Nones is a book of poems by W. H. Auden published in 1951 by Faber & Faber. The book contains Auden's shorter poems written between 1946 and 1950, including "In Praise of Limestone", "Prime", "Nones," "Memorial for the City", "Precious Five", and "A Walk After Dark".

Topographical poetry or loco-descriptive poetry is a genre of poetry that describes, and often praises, a landscape or place. John Denham's 1642 poem "Cooper's Hill" established the genre, which peaked in popularity in 18th-century England. Examples of topographical verse date, however, to the late classical period, and can be found throughout the medieval era and during the Renaissance. Though the earliest examples come mostly from continental Europe, the topographical poetry in the tradition originating with Denham concerns itself with the classics, and many of the various types of topographical verse, such as river, ruin, or hilltop poems were established by the early 17th century. Alexander Pope's "Windsor Forest" (1713) and John Dyer's "Grongar Hill" (1726/7) are two other often mentioned examples. In following centuries, Matthew Arnold's "The Scholar Gipsy" (1853) praised the Oxfordshire countryside, and W. H. Auden's "In Praise of Limestone" (1948) used a limestone landscape as an allegory.

This is a bibliography of books, plays, films, and libretti written, edited, or translated by the Anglo-American poet W. H. Auden (1907–1973). See the main entry for a list of biographical and critical studies and external links. Dates are dates of publication of performance, not of composition.

Joan Vincent Murray was a Canadian American poet.

"The Platonic Blow, by Miss Oral" is an erotic poem by W. H. Auden. Thought to have been written in 1948, the poem gleefully describes in graphic detail a homosexual encounter involving an act of fellatio.

Poetic devices are a form of literary device used in poetry. Poems are created out of poetic devices via a composite of: structural, grammatical, rhythmic, metrical, verbal, and visual elements. They are essential tools that a poet uses to create rhythm, enhance a poem's meaning, or intensify a mood or feeling.