Related Research Articles

In phonology, an allophone is one of multiple possible spoken sounds – or phones – used to pronounce a single phoneme in a particular language. For example, in English, the voiceless plosive and the aspirated form are allophones for the phoneme, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in some languages such as Central Thai. Similarly, in Spanish, and are allophones for the phoneme, while these two are considered to be different phonemes in English.

In phonetics, a nasal, also called a nasal occlusive or nasal stop in contrast with an oral stop or nasalized consonant, is an occlusive consonant produced with a lowered velum, allowing air to escape freely through the nose. The vast majority of consonants are oral consonants. Examples of nasals in English are, and, in words such as nose, bring and mouth. Nasal occlusives are nearly universal in human languages. There are also other kinds of nasal consonants in some languages.

Unless otherwise noted, statements in this article refer to Standard Finnish, which is based on the dialect spoken in the former Häme Province in central south Finland. Standard Finnish is used by professional speakers, such as reporters and news presenters on television.

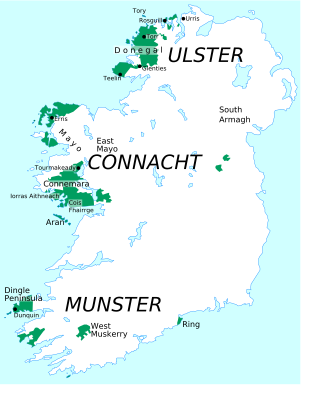

Irish phonology varies from dialect to dialect; there is no standard pronunciation of Irish. Therefore, this article focuses on phenomena shared by most or all dialects, and on the major differences among the dialects. Detailed discussion of the dialects can be found in the specific articles: Ulster Irish, Connacht Irish, and Munster Irish.

The phonology of Portuguese varies among dialects, in extreme cases leading to some difficulties in mutual intelligibility. This article on phonology focuses on the pronunciations that are generally regarded as standard. Since Portuguese is a pluricentric language, and differences between European Portuguese (EP), Brazilian Portuguese (BP), and Angolan Portuguese (AP) can be considerable, varieties are distinguished whenever necessary.

This article is about the phonology and phonetics of the Spanish language. Unless otherwise noted, statements refer to Castilian Spanish, the standard dialect used in Spain on radio and television. For historical development of the sound system, see History of Spanish. For details of geographical variation, see Spanish dialects and varieties.

English phonology is the system of speech sounds used in spoken English. Like many other languages, English has wide variation in pronunciation, both historically and from dialect to dialect. In general, however, the regional dialects of English share a largely similar phonological system. Among other things, most dialects have vowel reduction in unstressed syllables and a complex set of phonological features that distinguish fortis and lenis consonants.

Old English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative since Old English is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large corpus of the language, and its orthography apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully and so certain conclusions can easily be drawn.

The phonology of the Ojibwe language varies from dialect to dialect, but all varieties share common features. Ojibwe is an indigenous language of the Algonquian language family spoken in Canada and the United States in the areas surrounding the Great Lakes, and westward onto the northern plains in both countries, as well as in northeastern Ontario and northwestern Quebec. The article on Ojibwe dialects discusses linguistic variation in more detail, and contains links to separate articles on each dialect. There is no standard language and no dialect that is accepted as representing a standard. Ojibwe words in this article are written in the practical orthography commonly known as the Double vowel system.

The phonology of Quebec French is more complex than that of Parisian or Continental French. Quebec French has maintained phonemic distinctions between and, and, and, and. The latter phoneme of each minimal pair has disappeared in Parisian French, and only the last distinction has been maintained in Meridional French though all of those distinctions persist in Swiss and Belgian French.

The phonological system of the Hawaiian language is based on documentation from those who developed the Hawaiian alphabet during the 1820s as well as scholarly research conducted by lexicographers and linguists from 1949 to present.

The phonology of Bengali, like that of its neighbouring Eastern Indo-Aryan languages, is characterised by a wide variety of diphthongs and inherent back vowels.

Unlike many languages, Icelandic has only very minor dialectal differences in sounds. The language has both monophthongs and diphthongs, and many consonants can be voiced or unvoiced.

Tamil phonology is characterised by the presence of "true-subapical" retroflex consonants and multiple rhotic consonants. Its script does not distinguish between voiced and unvoiced consonants; phonetically, voice is assigned depending on a consonant's position in a word, voiced intervocalically and after nasals except when geminated. Tamil phonology permits few consonant clusters, which can never be word initial.

The phonology of Sesotho and those of the other Sotho–Tswana languages are radically different from those of "older" or more "stereotypical" Bantu languages. Modern Sesotho in particular has very mixed origins inheriting many words and idioms from non-Sotho–Tswana languages.

The Gujarati language is an Indo-Aryan language native to the Indian state of Gujarat. Much of its phonology is derived from Sanskrit.

Hindustani is the lingua franca of northern India and Pakistan, and through its two standardized registers, Hindi and Urdu, a co-official language of India and co-official and national language of Pakistan respectively. Phonological differences between the two standards are minimal.

Taos is a Tanoan language spoken by several hundred people in New Mexico, in the United States. The main description of its phonology was contributed by George L. Trager in a (pre-generative) structuralist framework. Earlier considerations of the phonetics-phonology were by John P. Harrington and Jaime de Angulo. Trager's first account was in Trager (1946) based on fieldwork 1935-1937, which was then substantially revised in Trager (1948). The description below takes Trager (1946) as the main point of departure and notes where this differs from the analysis of Trager (1948). Harrington's description is more similar to Trager (1946). Certain comments from a generative perspective are noted in a comparative work Hale (1967).

The phonology of Welsh is characterised by a number of sounds that do not occur in English and are rare in European languages, such as the voiceless alveolar lateral fricative and several voiceless sonorants, some of which result from consonant mutation. Stress usually falls on the penultimate syllable in polysyllabic words, while the word-final unstressed syllable receives a higher pitch than the stressed syllable.

Kensiu (Kensiw) is an Austroasiatic language of the Jahaic subbranch. It is spoken by a small community of 300 people in Yala Province in southern Thailand and also reportedly by a community of approximately 300 speakers in Western Malaysia in Perak and Kedah states. Speakers of this language are Negritos who are known as the Maniq people or Mani of Thailand. In Malaysia, they are counted among the Orang Asli.

References

- Dixon, R. M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 589–601.