An amplifier, electronic amplifier or (informally) amp is an electronic device that can increase the magnitude of a signal. It is a two-port electronic circuit that uses electric power from a power supply to increase the amplitude of a signal applied to its input terminals, producing a proportionally greater amplitude signal at its output. The amount of amplification provided by an amplifier is measured by its gain: the ratio of output voltage, current, or power to input. An amplifier is defined as a circuit that has a power gain greater than one.

In radio engineering and telecommunications, standing wave ratio (SWR) is a measure of impedance matching of loads to the characteristic impedance of a transmission line or waveguide. Impedance mismatches result in standing waves along the transmission line, and SWR is defined as the ratio of the partial standing wave's amplitude at an antinode (maximum) to the amplitude at a node (minimum) along the line.

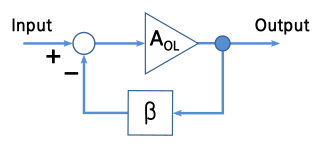

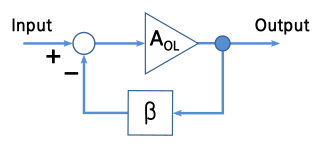

A negative-feedback amplifier is an electronic amplifier that subtracts a fraction of its output from its input, so that negative feedback opposes the original signal. The applied negative feedback can improve its performance and reduces sensitivity to parameter variations due to manufacturing or environment. Because of these advantages, many amplifiers and control systems use negative feedback.

In electronics, negative resistance (NR) is a property of some electrical circuits and devices in which an increase in voltage across the device's terminals results in a decrease in electric current through it.

In electrical engineering, impedance matching is the practice of designing or adjusting the input impedance or output impedance of an electrical device for a desired value. Often, the desired value is selected to maximize power transfer or minimize signal reflection. For example, impedance matching typically is used to improve power transfer from a radio transmitter via the interconnecting transmission line to the antenna. Signals on a transmission line will be transmitted without reflections if the transmission line is terminated with a matching impedance.

In electronics, a voltage divider (also known as a potential divider) is a passive linear circuit that produces an output voltage (Vout) that is a fraction of its input voltage (Vin). Voltage division is the result of distributing the input voltage among the components of the divider. A simple example of a voltage divider is two resistors connected in series, with the input voltage applied across the resistor pair and the output voltage emerging from the connection between them.

In electronics, a buffer amplifier is a unity gain amplifier that copies a signal from one circuit to another while transforming its electrical impedance to provide a more ideal source. This "buffers" the signal source in the first circuit against being affected by currents from the electrical load of the second circuit and may simply be called a buffer or follower when context is clear.

An antenna tuner, a matchbox, transmatch, antenna tuning unit (ATU), antenna coupler, or feedline coupler is a device connected between a radio transmitter or receiver and its antenna to improve power transfer between them by matching the impedance of the radio to the antenna's feedline. Antenna tuners are particularly important for use with transmitters. Transmitters feed power into a resistive load, very often 50 ohms, for which the transmitter is optimally designed for power output, efficiency, and low distortion. If the load seen by the transmitter departs from this design value due to improper tuning of the antenna/feedline combination the power output will change, distortion may occur and the transmitter may overheat.

In audio engineering and sound recording, a high impedance bridging, voltage bridging, or simply bridging connection is one in which the load impedance is much larger than the source impedance. The load measures the source's voltage while minimally drawing current or affecting it.

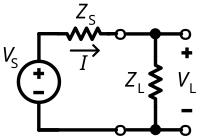

In electrical engineering, the output impedance of an electrical network is the measure of the opposition to current flow (impedance), both static (resistance) and dynamic (reactance), into the load network being connected that is internal to the electrical source. The output impedance is a measure of the source's propensity to drop in voltage when the load draws current, the source network being the portion of the network that transmits and the load network being the portion of the network that consumes.

Line level is the specified strength of an audio signal used to transmit analog sound between audio components such as CD and DVD players, television sets, audio amplifiers, and mixing consoles.

Scattering parameters or S-parameters describe the electrical behavior of linear electrical networks when undergoing various steady state stimuli by electrical signals.

The cascode is a two-stage amplifier that consists of a common emitter stage feeding into a common base stage when using bipolar junction transistors (BJTs) or alternatively a common source stage feeding a common gate stage when using field-effect transistors (FETs).

This article illustrates some typical operational amplifier applications. A non-ideal operational amplifier's equivalent circuit has a finite input impedance, a non-zero output impedance, and a finite gain. A real op-amp has a number of non-ideal features as shown in the diagram, but here a simplified schematic notation is used, many details such as device selection and power supply connections are not shown. Operational amplifiers are optimised for use with negative feedback, and this article discusses only negative-feedback applications. When positive feedback is required, a comparator is usually more appropriate. See Comparator applications for further information.

An electrical load is an electrical component or portion of a circuit that consumes (active) electric power, such as electrical appliances and lights inside the home. The term may also refer to the power consumed by a circuit. This is opposed to a power supply source, such as a battery or generator, which provides power.

An attenuator is a passive broadband electronic device that reduces the power of a signal without appreciably distorting its waveform.

A Wilson current mirror is a three-terminal circuit that accepts an input current at the input terminal and provides a "mirrored" current source or sink output at the output terminal. The mirrored current is a precise copy of the input current.

A test probe is a physical device used to connect electronic test equipment to a device under test (DUT). Test probes range from very simple, robust devices to complex probes that are sophisticated, expensive, and fragile. Specific types include test prods, oscilloscope probes and current probes. A test probe is often supplied as a test lead, which includes the probe, cable and terminating connector.

An L pad is a network composed of two impedances that typically resemble the letter capital "L" when drawn on a schematic circuit diagram. It is commonly used for attenuation and for impedance matching.

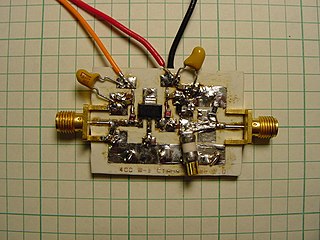

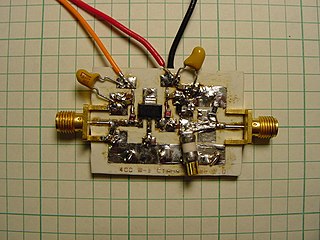

A radio-frequency power amplifier is a type of electronic amplifier that converts a low-power radio-frequency (RF) signal into a higher-power signal. Typically, RF power amplifiers are used in the final stage of a radio transmitter, their output driving the antenna. Design goals often include gain, power output, bandwidth, power efficiency, linearity, input and output impedance matching, and heat dissipation.