Human rights are moral principles, or norms, for certain standards of human behaviour and are regularly protected as substantive rights in substantive law, municipal and international law. They are commonly understood as inalienable, fundamental rights "to which a person is inherently entitled simply because she or he is a human being" and which are "inherent in all human beings", regardless of their age, ethnic origin, location, language, religion, ethnicity, or any other status. They are applicable everywhere and at every time in the sense of being universal, and they are egalitarian in the sense of being the same for everyone. They are regarded as requiring empathy and the rule of law, and imposing an obligation on persons to respect the human rights of others; it is generally considered that they should not be taken away except as a result of due process based on specific circumstances.

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, it was accepted by the General Assembly as Resolution 217 during its third session on 10 December 1948 at the Palais de Chaillot in Paris, France. Of the 58 members of the United Nations at the time, 48 voted in favour, none against, eight abstained, and two did not vote.

The Charter of the United Nations (UN) is the foundational treaty of the United Nations. It establishes the purposes, governing structure, and overall framework of the UN system, including its six principal organs: the Secretariat, the General Assembly, the Security Council, the Economic and Social Council, the International Court of Justice, and the Trusteeship Council.

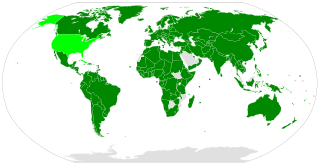

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) is a multilateral treaty that commits nations to respect the civil and political rights of individuals, including the right to life, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, electoral rights and rights to due process and a fair trial. It was adopted by United Nations General Assembly Resolution 2200A (XXI) on 16 December 1966 and entered into force on 23 March 1976 after its thirty-fifth ratification or accession. As of June 2022, the Covenant has 173 parties and six more signatories without ratification, most notably the People's Republic of China and Cuba; North Korea is the only state that has tried to withdraw.

Children's rights or the rights of children are a subset of human rights with particular attention to the rights of special protection and care afforded to minors. The 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) defines a child as "any human being below the age of eighteen years, unless under the law applicable to the child, majority is attained earlier." Children's rights includes their right to association with both parents, human identity as well as the basic needs for physical protection, food, universal state-paid education, health care, and criminal laws appropriate for the age and development of the child, equal protection of the child's civil rights, and freedom from discrimination on the basis of the child's race, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, national origin, religion, disability, color, ethnicity, or other characteristics.

The right to work is the concept that people have a human right to work, or to engage in productive employment, and should not be prevented from doing so. The right to work, enshrined in the United Nations 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, is recognized in international human-rights law through its inclusion in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, where the right to work emphasizes economic, social and cultural development.

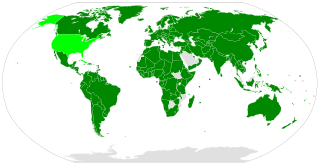

The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) is a multilateral treaty adopted by the United Nations General Assembly (GA) on 16 December 1966 through GA. Resolution 2200A (XXI), and came into force on 3 January 1976. It commits its parties to work toward the granting of economic, social, and cultural rights (ESCR) to all individuals including those living in Non-Self-Governing and Trust Territories. The rights include labour rights, the right to health, the right to education, and the right to an adequate standard of living. As of February 2024, the Covenant has 172 parties. A further four countries, including the United States, have signed but not ratified the Covenant.

Economic, social and cultural rights (ESCR) are socio-economic human rights, such as the right to education, right to housing, right to an adequate standard of living, right to health, victims' rights and the right to science and culture. Economic, social and cultural rights are recognised and protected in international and regional human rights instruments. Member states have a legal obligation to respect, protect and fulfil economic, social and cultural rights and are expected to take "progressive action" towards their fulfilment.

The Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action (VDPA) is a human rights declaration adopted by consensus at the World Conference on Human Rights on 25 June 1993 in Vienna, Austria. The position of United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights was recommended by this Declaration and subsequently created by General Assembly Resolution 48/141.

The U.S. Department of State's Country Report on Human Rights Practices for São Tomé and Príncipe states that the government generally respects the human rights of its citizens, despite problems in a few areas.

The right to food, and its variations, is a human right protecting the right of people to feed themselves in dignity, implying that sufficient food is available, that people have the means to access it, and that it adequately meets the individual's dietary needs. The right to food protects the right of all human beings to be free from hunger, food insecurity, and malnutrition. The right to food implies that governments only have an obligation to hand out enough free food to starving recipients to ensure subsistence, it does not imply a universal right to be fed. Also, if people are deprived of access to food for reasons beyond their control, for example, because they are in detention, in times of war or after natural disasters, the right requires the government to provide food directly.

The right to sexuality incorporates the right to express one's sexuality and to be free from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation. Specifically, it relates to the human rights of people of diverse sexual orientations, including lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) people, and the protection of those rights, although it is equally applicable to heterosexuality. The right to sexuality and freedom from discrimination on the grounds of sexual orientation is based on the universality of human rights and the inalienable nature of rights belonging to every person by virtue of being human.

Human rights and climate change is a conceptual and legal framework under which international human rights and their relationship to global warming are studied, analyzed, and addressed. The framework has been employed by governments, United Nations organizations, intergovernmental and non-governmental organizations, human rights and environmental advocates, and academics to guide national and international policy on climate change under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the core international human rights instruments. In 2022 Working Group II of the IPCC suggested that "climate justice comprises justice that links development and human rights to achieve a rights-based approach to addressing climate change".

The Voluntary Guidelines to support the Progressive Realization of the Right to Adequate Food in the Context of National Food Security, also known as the Right to Food Guidelines, is a document adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in 2004, with the aim of guiding states to implement the right to food. It is not legally binding, but directed to states' obligations to the right to food under international law. In specific, it is directed towards States Parties to the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) and to States that still have to ratify it.

The Universal Declaration on the Eradication of Hunger and Malnutrition was adopted on 16 November 1974, by governments who attended the 1974 World Food Conference that was convened under General Assembly resolution 3180 (XXVIII) of 17 December 1973. It was later endorsed by General Assembly resolution 3348 (XXIX), of 17 December 1974. This Declaration combined discussions of the international human right to adequate food and nutrition with an acknowledgement of the various economic and political issues that can affect the production and distribution of food related products. Within this Declaration, it is recognised that it is the common purpose of all nations to work together towards eliminating hunger and malnutrition. Further, the Declaration explains how the welfare of much of the world's population depends on their ability to adequately produce and distribute food. In doing so, it emphasises the need for the international community to develop a more adequate system to ensure that the right to food for all persons is recognised. The opening paragraph of the Declaration, which remains to be the most recited paragraph of the Declaration today, reads:

Every man, woman and child has the inalienable right to be free from hunger and malnutrition in order to develop fully and maintain their physical and mental faculties.

This section provides an overview of the status of the right to food at a national level.

Development is a human right that belongs to everyone, individually and collectively. Everyone is “entitled to participate in, contribute to, and enjoy economic, social, cultural and political development, in which all human rights and fundamental freedoms can be fully realized,” states the groundbreaking UN Declaration on the Right to Development, proclaimed in 1986.

The right to an adequate standard of living is a fundamental human right. It is part of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights that was accepted by the General Assembly of the United Nations on December 10, 1948.

Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of him/herself and of his/her family, including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond his/her control.

The Declaration on the Rights of Peasants is an UNGA resolution on human rights with "universal understanding", adopted by the United Nations in 2018. The resolution was passed by a vote of 121-8, with 54 members abstaining.

The right to a healthy environment or the right to a sustainable and healthy environment is a human right advocated by human rights organizations and environmental organizations to protect the ecological systems that provide human health. The right was acknowledged by the United Nations Human Rights Council during its 48th session in October 2021 in HRC/RES/48/13 and subsequently by the United Nations General Assembly on July 28, 2022 in A/RES/76/300. The right is often the basis for human rights defense by environmental defenders, such as land defenders, water protectors and indigenous rights activists.