Related Research Articles

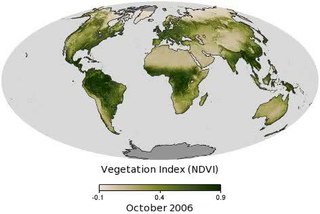

Vegetation is an assemblage of plant species and the ground cover they provide. It is a general term, without specific reference to particular taxa, life forms, structure, spatial extent, or any other specific botanical or geographic characteristics. It is broader than the term flora which refers to species composition. Perhaps the closest synonym is plant community, but vegetation can, and often does, refer to a wider range of spatial scales than that term does, including scales as large as the global. Primeval redwood forests, coastal mangrove stands, sphagnum bogs, desert soil crusts, roadside weed patches, wheat fields, cultivated gardens and lawns; all are encompassed by the term vegetation.

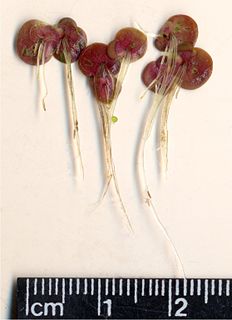

Spirodela is a genus of aquatic plants, one of several genera containing plants commonly called duckweed. Spirodela species are members of the Araceae under the APG II system. They were formerly members of the Lemnaceae.

The Raunkiær system is a system for categorizing plants using life-form categories, devised by Danish botanist Christen C. Raunkiær and later extended by various authors.

Phytosociology, also known as phytocoenology or simply plant sociology, is the study of groups of species of plant that are usually found together. Phytosociology aims to empirically describe the vegetative environment of a given territory. A specific community of plants is considered a social unit, the product of definite conditions, present and past, and can exist only when such conditions are met. In phytosociology such as unit is known as a phytocoenosis. A phytocoenosis is more commonly known as a plant community, and consists of the sum of all plants in a given area. It is a subset of a biocoenosis, which consists of all organisms in a given area. More strictly speaking, a phytocoenosis is a set of plants in area that are interacting with each other through competition or other ecological processes. Coenoses are not equivalent to ecosystems, which consist of organisms and the physical environment that they interact with. A phytocoensis has a distribution which can be mapped. Phytosociology has a system for describing and classifying these phytocoenoses in a hierarchy, known as syntaxonomy, and this system has a nomenclature. The science is most advanced in Europe, Africa and Asia.

Wolffia is a genus of nine to 11 species which include the smallest flowering plants on Earth. Commonly called watermeal or duckweed, these aquatic plants resemble specks of cornmeal floating on the water. Wolffia species are free-floating thalli, green or yellow-green, and without roots. The flower is produced in a depression on the top surface of the plant body. It has one stamen and one pistil. Individuals often float together in pairs or form floating mats with related plants, such as Lemna and Spirodela species. Most species have a very wide distribution across several continents. Wolffia species are composed of about 40% protein on a dry-matter basis, about the same as the soybean, making them a potential high-protein human food source. They have historically been collected from the water and eaten as a vegetable in much of Asia.

Indicator value is a term that has been used in ecology for two different indices. The older usage of the term refers to Ellenberg's indicator values, which are based on a simple ordinal classification of plants according to the position of their realized ecological niche along an environmental gradient. More recently, the term has also been used to refer to Dufrêne & Legendre's indicator value, which is a quantitative index that measures the statistical alliance of a species to any one of the classes in a classification of sites.

Phytogeography or botanical geography is the branch of biogeography that is concerned with the geographic distribution of plant species and their influence on the earth's surface. Phytogeography is concerned with all aspects of plant distribution, from the controls on the distribution of individual species ranges to the factors that govern the composition of entire communities and floras. Geobotany, by contrast, focuses on the geographic space's influence on plants.

Johannes Iversen was a Danish palaeoecologist and plant ecologist.

Carl Emil Hansen Ostenfeld was a Danish systematic botanist. He graduated from the University of Copenhagen under professor Eugenius Warming. He was a keeper at the Botanical Museum 1900–1918, when he became professor of botany at the Royal Veterinary and Agricultural University. In 1923, by the early retirement of Raunkiær's, Ostenfeld became professor of botany at the University of Copenhagen and director of the Copenhagen Botanical Garden, both positions held until his death in 1931. He was a member of the Royal Danish Academy of Sciences and Letters and served on the board of directors of the Carlsberg Foundation.

Thekla Susanne Ragnhild Resvoll was a Norwegian botanist and educator. She was a pioneer in Norwegian natural history education and nature conservation together with her sister, Hanna Resvoll-Holmsen.

Lucien Leon Hauman-Merck was a Belgian botanist, who studied and collected plants in South America and Africa.

Friedrich Karl Max Vierhapper was an Austrian plant collector, botanist and professor of botany at the University of Vienna. He was the son of amateur botanist Friedrich Vierhapper (1844–1903), botanical abbreviation- "F.Vierh.".

Otto Sendtner was a German botanist and phytogeographer born in Munich.

Morocco provides a refuge for a rich and diverse flora with about 4,200 taxa, of which 22% are endemic. The phytogeographic zones of Morocco comprise 8 zones: the Mediterranean zone, the Cedar zone (1000-2000m), the sub-Alpine zone (2,000-2,500m), the Alpine zone (2,500m+), the semi-desert scrub zone, the Reg, the sandy desert zone and the oases.

Vegetation classification is the process of classifying and mapping the vegetation over an area of the earth's surface. Vegetation classification is often performed by state based agencies as part of land use, resource and environmental management. Many different methods of vegetation classification have been used. In general, there has been a shift from structural classification used by forestry for the mapping of timber resources, to floristic community mapping for biodiversity management. Whereas older forestry-based schemes considered factors such as height, species and density of the woody canopy, floristic community mapping shifts the emphasis onto ecological factors such as climate, soil type and floristic associations. Classification mapping is usually now done using geographic information systems (GIS) software.

Anton Schneeberger was a Swiss botanist, doctor, and book collector based in Poland.

Hubert Winkler was a German botanist, who specialized in tropical flora research.

Berta Rahm was a Swiss architect, writer, publisher, and feminist activist.

Dr. Marie Charlotte Brockmann-Jerosch, was a Swiss botanist noted for her influential research on alpine flora and phylogeography. She received her Ph.D. from the University of Zurich in 1905. She was married to Heinrich Brockmann-Jerosch, and in 1913 they both joined the second International Phytogeographic Excursion, a two-month tour of by international scientists of North American biogeography, exploring New York, Illinois, Michigan, Nebraska, and Colorado.

Elias Landolt (1926–2013) was a Swiss geobotanist, known for his publications on Switzerland's native flora and Lemnoideae.

References

- ↑ Claridge Druce, G. (1912) The International Phytogeographical Excursion in the British Isles. X. Additional Floristic Notes. New Phytologist 11 (9): 354-363.

- ↑ Ostenfeld, C. E. H. 1912. Some remarks on the International Phytogeographic Excursion in the British Isles. New Phytologist , 11: 114-127.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Science 37 (949): 377, 1913

- ↑ The Library of Congress - Ecology and the American Environment

- ↑ "Carl Schroeter photo album". Archived from the original on 2011-07-25. Retrieved 2007-10-26.

- ↑ Dachnowski, A. (1914) The International Phytogeographic Excursion of 1913 and its Significance to Ecology in America. Journal of Ecology 2 (4): 237-245.

- ↑ ESA History

- ↑ Harshberger, J. W. (1924) The Third International Phytogeographic Excursion. Ecology 5 (3): 287-289.

- ↑ Salisbury, E.J. (1925) Some Impressions of the International Phytogeographical Excursion in Switzerland, 1923. Journal of Ecology 13 (1): 161-164

- ↑ Raber, Oran (1925) The Fourth International Phytogeographic Excursion. Science 62 (1607): 344-345

- ↑ Rübel, E. (ed.) (1927) Ergebnisse der internationalen pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch Schweden und Norwegen 1925. Veröffentlichungen des geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 4

- ↑ Domin, K. (1928) Introductory Remarks to the Fifth International Phytogeographic Excursion (I.P.E.) through Czechoslovakia. Acta Botanica Bohemica 6-7: 3-76

- ↑ Rübel, E. (ed.) (1930) Ergebnisse der internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch die Tschechoslowakei und Polen 1928. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 6

- ↑ Rübel, E. (ed.) (1933) Ergebnisse der Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exursion durch Rumänien 1931. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 10

- ↑ Rübel, E. (ed.) (1936) Ergebnisse der Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch Mittelitalien 1934. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 12

- ↑ Rübel, E. & Lüdi, W. (eds) (1936) Ergebnisse der Internationalen pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch Marokko und Westalgerien 1936. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 14

- ↑ Lüdi, Werner (ed.) (1952) Die Pflanzenwelt Irlands (The flora and vegetation of Ireland): Ergebnisse der 9. Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch Irland 1949. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 25

- ↑ Richards, P.W. (1953) Tenth International Phytogeographical Excursion. Nature 172 (4378): 566-568

- ↑ Lüdi, Werner, Tüxen, Reinhold & Oberdorfer, Erich (ed.) (1956-1958) Die Pflanzenwelt Spaniens: Ergebnisse der 10. Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion (IPE) durch Spanien 1953, vol. 1-2. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 31-32

- ↑ Lüdi, Werner (ed.)Ergebnisse der Internationalen pflanzengeographischen Exkursion durch die Ostalpen 1956. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes Rübel in Zürich, 35

- ↑ Lüdi, Werner (ed.) (1961) Die Pflanzenwelt der Tschechoslowakei : Ergebnisse der 12. Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion (IPE) durch die Tschechoslowakei 1958. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich 36.

- ↑ Ozenda, P. & Landolt, E. (eds) (1970) Zur Vegetation und Flora der Westalpen : Ergebnisse der 14. Internationalen pflanzengeographischen Exkursion (IPE) durch die Westalpen. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich, 43

- ↑ Dafis, Sp. & Landolt, E. (eds) (1975-1976) Zur Vegetation und Flora von Griechenland : Ergebnisse der 15. Internationalen Pflanzengeographischen Exkursion (IPE) durch Griechenland 1971, vol. 1-2. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich, 55-56

- ↑ Lieth, H., Landolt, E. & Peet, R.K. (eds) (1979-1981) Contributions to the knowledge of flora and vegetation in the Carolinas: proceedings of the 16th International phytogeographical excursion (IPE), 1978, through the SE United States, vol. 1-2. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich 68-69 + 77

- ↑ Eskuche, U. & Landolt, E. (eds) (1986) Contributions to the knowledge of flora and vegetation of northern Argentina: proceedings of the 17th International Phytogeographic Excursion (IPE), 1983, through northern Argentina. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich, 91

- ↑ Miyawaki, A. & Landolt, E. (eds) (1988) Contributions to the knowledge of flora and vegetation of Japan: proceedings of the 18th International Phytogeographic Excursion (IPE), 1984, through central Japan. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich, 98.

- ↑ Zarzycki, K., Landolt, E. & Wojcicki, J.J. (eds) (1991-1992) Contributions to the knowledge of flora and vegetation of Poland: proceedings of the 19th International Phytogeographic Excursion (IPE), 1989, through Poland, vol. 1-2. Veröffentlichungen des Geobotanischen Institutes der ETH, Stiftung Rübel, Zürich, 106-107