Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

The ceinture fléchée or is a type of colourful sash, a traditional piece of Québécois clothing linked to at least the 17th century. The Métis also adopted and made ceintures fléchées and use them as part of their national regalia. Québécois and Métis communities share the sash as an important part of their distinct cultural heritages, nationalities, attires, histories and resistances. While the traditional view is that the ceinture fléchée is a Québécois invention, other origins have been suggested as well including the traditional fingerwoven Gaelic crios. According to Dorothy K. Burnham who prepared an exhibit on textiles at the National Gallery of Canada in 1981, and published an accompanying catalogue raisonné, this type of finger weaving was learned by residents of New France from Indigenous peoples. With European wool-materials, the syncretism and unification of Northern French and Indigenous finger-weaving techniques resulted in the making of Arrowed Sashes. Arrow Sash is the oldest known sash design; produced by Québécois artisans in XVIIIth century, and later on L'Assomption sash after 1852.

A balanced fabric is one in which the warp and the weft are of the same size. In weaving, these are generally called "balanced plain weaves" or just "balanced weaves", while in embroidery the term "even-weave" is more common.

Maya textiles (k’apak) are the clothing and other textile arts of the Maya peoples, indigenous peoples of the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Belize. Women have traditionally created textiles in Maya society, and textiles were a significant form of ancient Maya art and religious beliefs. They were considered a prestige good that would distinguish the commoners from the elite. According to Brumfiel, some of the earliest weaving found in Mesoamerica can date back to around 1000-800 B.C.E.

Navajo weaving are textiles produced by Navajo people, who are based near the Four Corners area of the United States. Navajo textiles are highly regarded and have been sought after as trade items for more than 150 years. Commercial production of handwoven blankets and rugs has been an important element of the Navajo economy. As one art historian wrote, "Classic Navajo serapes at their finest equal the delicacy and sophistication of any pre-mechanical loom-woven textile in the world."

The visual arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas encompasses the visual artistic practices of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas from ancient times to the present. These include works from South America and North America, which includes Central America and Greenland. The Siberian Yupiit, who have great cultural overlap with Native Alaskan Yupiit, are also included.

Dorothy Wright Liebes was an American textile designer and weaver renowned for her innovative, custom-designed modern fabrics for architects and interior designers. She was known as "the mother of modern weaving".

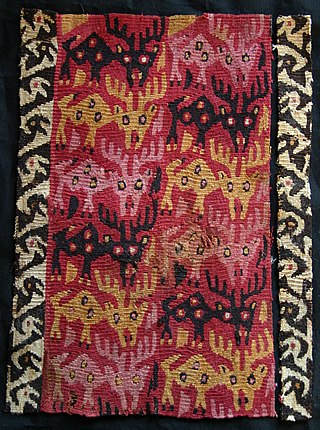

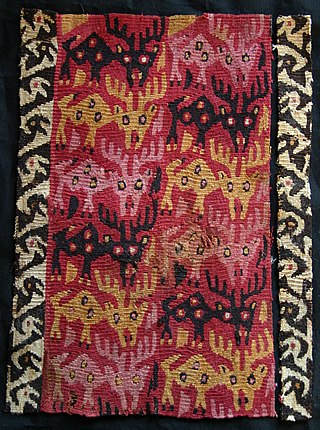

The textile arts of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas are decorative, utilitarian, ceremonial, or conceptual artworks made from plant, animal, or synthetic fibers by Indigenous peoples of the Americas.

The Martha Graham Dance Company, founded by Martha Graham in 1926, is both the oldest dance company in the United States and the oldest integrated dance company. The company is critically acclaimed in the artistic world and has been recognized as "one of the great dance companies of the world" by the New York Times and as "one of the seven wonders of the artistic universe" by the Washington Post.

Marta Turok is a Mexican applied anthropologist focusing on socio-economic development, and one of the foremost schools on Mexican folk art. Through research, government work, education and advocacy, she has worked to raise the prestige of Mexican handcrafts and folk art and to help artisans improve their economic status. Her work has been recognized with awards from various governmental and non-governmental agencies.

Irene Hardy Clark is a Navajo weaver. Her matrilineal clan is Tabaahi and her patrilineal clan is Honagha nii. Her technique and style is primarily self-taught, incorporating contemporary and traditional themes.

Mary Holiday Black was a Navajo basket maker and textile weaver from Halchita, Utah. During the 1970s, in response to a long-term decline in Navajo basketry, Black played a key role in the revival of Navajo basket weaving by experimenting with new designs and techniques, pioneering a new style of Navajo baskets known as "story baskets."

D.Y. Begay is a Navajo textile artist born into the Tóʼtsohnii Clan and born from the Táchiiʼnii Clan.

Melissa Cody is a Navajo textile artist from No Water Mesa, Arizona, United States. Her Germantown Revival style weavings are known for their bold colors and intricate three dimensional patterns. Cody maintains aspects of traditional Navajo tapestries, but also adds her own elements into her work. These elements range from personal tributes to pop culture references.

Tyra Shackleford is a Chickasaw textile artist who specializes in various hand woven techniques. Her three most prominent weaving techniques are sprang, fingerweaving, and twinning, which all date back prior to European contact, She has opened her traditional form of art to more conceptual and wearable art.

Kate Peck Kent, born Kate Stott Peck, was an American anthropologist who studied the history of Pueblo and Navajo textiles.

Karen Hampton is an American textile artist, working as a weaver, surface designer, and fabric dyer. She has also worked as a researcher on the history of textile production. As of 2022, she was named a Fellow of the American Craft Council. Hampton lives in Los Angeles.

Evelyn Vanderhoop is a Haida Nation artist from Masset, British Columbia, Canada. She paints and is a textile artist, specializing in Chilkat weaving and Raven's Tail weaving.

Barbara Teller Ornelas is a Native American weaver and citizen of the Navajo Nation. She also is an instructor and author about this art. She has served overseas as a cultural ambassador for the U.S. State Department. A fifth-generation Navajo weaver, she exhibits her fine art textiles and educates about Navajo culture at home and abroad.

Daisy Taugelchee was a Navajo weaver. The Denver Art Museum declared Taugelchee as "widely considered the most talented Navajo weaver and spinner who ever lived". In 2004 one of her rugs was featured on a United States Postal Service stamp.