Related Research Articles

The Muscogee, also known as the Mvskoke, Muscogee Creek or just Creek, and the Muscogee Creek Confederacy, are a group of related Indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands in the United States. Their historical homelands are in what now comprises southern Tennessee, much of Alabama, western Georgia and parts of northern Florida.

Okmulgee County is a county in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. As of the 2020 census, the population was 36,706. The county seat is Okmulgee. Located within the Muscogee Nation Reservation, the county was created at statehood in 1907. The name Okmulgee is derived from the Hitchita word okimulgi, meaning "boiling waters".

Okmulgee is a city in, and the county seat of, Okmulgee County, Oklahoma. The name is from the Mvskoke word okimulgee, which means "boiling waters". The site was chosen because of the nearby rivers and springs. Okmulgee is 38 miles south of Tulsa and 13 miles north of Henryetta via US-75.

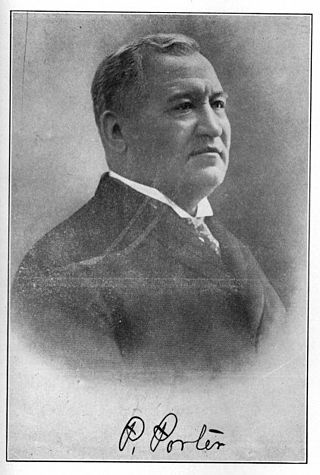

Pleasant Porter, was an American Indian statesman and the last elected Principal Chief of the Creek Nation, serving from 1899 until his death.

Lighthorse was the name given by the Five Civilized Tribes of the United States to their mounted police force. The Lighthorse were generally organized into companies and assigned to different districts. Perhaps the most famous were the Cherokee Lighthorsemen which had their origins in Georgia. Although the mounted police were disbanded when the Five Civilized Tribes lost their tribal lands in the late 19th century and their independence in 1906, some tribes still use the Lighthorse name for elements of their police forces.

Ocmulgee Mounds National Historical Park in Macon, Georgia, United States preserves traces of over ten millennia of culture from the Native Americans in the Southeastern Woodlands. Its chief remains are major earthworks built before 1000 CE by the South Appalachian Mississippian culture These include the Great Temple and other ceremonial mounds, a burial mound, and defensive trenches. They represented highly skilled engineering techniques and soil knowledge, and the organization of many laborers. The site has evidence of "12,000 years of continuous human habitation." The 3,336-acre (13.50 km2) park is located on the east bank of the Ocmulgee River. Macon, Georgia developed around the site after the United States built Fort Benjamin Hawkins nearby in 1806 to support trading with Native Americans.

Menawa, first called Hothlepoya, was a Muscogee (Creek) chief and military leader. He was of mixed race, with a Creek mother and a fur trader father of mostly Scots ancestry. As the Creek had a matrilineal system of descent and leadership, his status came from his mother's clan.

Samuel Benton Callahan was an influential, mixed blood Creek politician, born in Mobile, Alabama, to a white father, James Callahan, and Amanda Doyle, a mixed-blood Creek woman. He is listed as 1/8th Creek by Blood on the Dawes Rolls. One source says that James was an Irishman who had previously been an architect or a shipbuilder from Pennsylvania, while Amanda was one-fourth Muscogee. His father died while he was young; he and his mother were required to emigrate to Indian Territory in 1836. His mother married Dr. Owen Davis of Sulphur Springs, Texas, where they raised Samuel.

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke. Historically, they were often referred to by European Americans as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.

Chitto Harjo was a leader and orator among the traditionalists in the Muscogee Creek Nation in Indian Territory at the turn of the 20th century. He resisted changes which the US government and local leaders wanted to impose to achieve statehood for what became Oklahoma. These included extinguishing tribal governments and civic institutions and breaking up communal lands into allotments to individual households, with United States sales of the "surplus" to European-American and other settlers. He was the leader of the Crazy Snake Rebellion on March 25, 1909 in Oklahoma. At the time this was called the last "Indian uprising".

The Kialegee Tribal Town is a federally recognized Native American tribe in Oklahoma, as well as a traditional township within the former Muscogee Creek Confederacy in the American Southeast. Tribal members pride themselves on retaining their traditions and many still speak the Muscogee language. The name "Kialegee" comes from the Muscogee word, eka-lache, meaning "head left."

Benjamin Perryman (Steek-cha-ko-me-co) was a tribal town chief of some prominence among the Muscogee people in Alabama and was a pronounced adherent of the William McIntosh faction in Creek tribal affairs. He is noted as a signer of the Treaty of February 24, 1833 at Fort Gibson with the Government and, with Roley McIntosh, represented the Creeks at an intertribal conference with the western tribes which opened at Fort Gibson on September 2, 1834 and in these proceedings took an engaging part.

The Four Mothers Society or Four Mothers Nation is a religious, political, and traditionalist organization of Muscogee Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw and Chickasaw people, as well as the Natchez people enrolled in these tribes, in Oklahoma. It was formed in the 1890s as an opposition movement to the allotment policies of the Dawes Commission and various US Congressional acts of the period. The society is religious in nature. It opposed allotment because dividing tribal communal lands attacked the basis of their culture. In addition, some communal lands would be declared surplus and likely sold to non-Natives, causing the loss of their lands.

The Crazy Snake Rebellion, also known as the Smoked Meat Rebellion or Crazy Snake's War, was an incident in 1909 that at times was viewed as a war between the Creek people and American settlers. It should not be confused with an earlier, bloodless, conflict in 1901 involving many of the same people. The conflict consisted of only two minor skirmishes, the first of which was actually a struggle between a group of marginalized African Americans and a posse formed to punish the alleged robbery of a piece of smoked meat.

Nuyaka is a populated place in Okmulgee County, Oklahoma, United States. It is approximately 7.4 kilometres (4.6 mi) south-southwest of Beggs and is west of the city of Okmulgee off SH-56. The Old Nuyaka Cemetery and the Nuyaka Mission site are southwest of town. The elevation is 735 feet (224 m) and the coordinates are latitude 35.653 and longitude -96.14. It was notable as the center of traditionalist opposition to the Creek national government during the late 19th century.

Samuel Checote (1819–1884) (Muscogee) was a political leader, military veteran, and a Methodist preacher in the Creek Nation, Indian Territory. He served two terms as the first principal chief of the tribe to be elected under their new constitution created after the American Civil War. He had to deal with continuing tensions among his people, as traditionalists opposed assimilation to European-American ways.

Lois Harjo Ball (1906–1982) was a Native American painter, basket maker, and ceramic artist from Okmulgee, Oklahoma, and a citizen of the Muscogee Nation.

Sehoy, or Sehoy I, was an 18th-century matriarch of the Muscogee Confederacy and a member of the Wind clan.

Shelly Crow was an American nurse and nursing administrator, who worked for the Indian Health Service and was the first Muscogee woman elected to serve in the Muscogee Nation's executive branch. She was fourth elected Second Chief of the nation, serving from 1992 to 1996 in the administration of Chief Bill Fife.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 John Bartlett Meserve. Chronicles of Oklahoma. Vol. 10, No. 1, March 1932. "Chief Isparhecher." Retrieved April 24, 2013. Archived 2013-10-17 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "An Indian Royal Tiger." New York Times, Feb. 16, 1896. Accessed March 2, 2015.

- ↑ Agnew, Brad (22 February 2015). "Incursion by Watie led to battle on Barren Fork". Tahlequah Daily Press. Retrieved October 1, 2019.

- ↑ Ricky, Donald B. Indians of Oklahoma. "Isparhecher." (1999) ISBN 0-403-09865-3.

- ↑ Ricky, Donald B. Encyclopedia of Mississippi Indians: Tribes, Natives, Treaties. ISBN 978-0-403-09778-4.(2000)

- ↑ Kent Ruth (November 1975). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Isparhecher House and Grave". National Park Service . Retrieved February 25, 2022. With accompanying four photos from 1976