Aquila was an Italian aircraft carrier converted from the transatlantic passenger liner SS Roma. During World War II, Work on Aquila began in late 1941 at the Ansaldo shipyard in Genoa and continued for the next two years. With the signing of the Italian armistice on 8 September 1943, however, all work was halted and the vessel remained unfinished. She was captured by the National Republican Navy of the Italian Social Republic and the German occupation forces in 1943, but in 1945 she was partially sunk by a commando attack of Mariassalto, an Italian royalist assault unit of the Co-Belligerent Navy of the Kingdom of Italy, made up by members of the former Decima Flottiglia MAS. Aquila was eventually refloated and scrapped in 1952.

The Battle of the Mediterranean was the name given to the naval campaign fought in the Mediterranean Sea during World War II, from 10 June 1940 to 2 May 1945.

The naval Battle of Cape Bon took place on 13 December 1941 during the Second World War, between two Italian light cruisers and an Allied destroyer flotilla, off Cape Bon in Tunisia.

Trieste was the second of two Trento-class heavy cruisers built for the Italian Regia Marina. The ship was laid down in June 1925, was launched in October 1926, and was commissioned in December 1928. Trieste was very lightly armored, with only a 70 mm (2.8 in) thick armored belt, though she possessed a high speed and heavy main battery of eight 203 mm (8 in) guns. Though nominally built under the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty, the two cruisers significantly exceeded the displacement limits imposed by the treaty. The ship spent the 1930s conducting training cruises in the Mediterranean Sea, participating in naval reviews held for foreign dignitaries, and serving as the flagship of the Cruiser Division. She also helped transport Italian volunteer troops that had been sent to Spain to fight in the Spanish Civil War return to Italy in 1938.

Trento was the first of two Trento-class cruisers; they were the first heavy cruisers built for the Italian Regia Marina. The ship was laid down in February 1925, launched in October 1927, and was commissioned in April 1929. Trento was very lightly armored, with only a 70 mm (2.8 in) thick armored belt, though she possessed a high speed and heavy main battery of eight 203 mm (8 in) guns. Though nominally built under the restrictions of the Washington Naval Treaty, the two cruisers significantly exceeded the displacement limits imposed by the treaty.

The Capitani Romani class was a class of light cruisers acting as flotilla leaders for the Regia Marina. They were built to outrun and outgun the large new French destroyers of the Le Fantasque and Mogador classes. Twelve hulls were ordered in late 1939, but only four were completed, just three of these before the Italian armistice in 1943. The ships were named after prominent ancient Romans.

Luigi Cadorna was an Italian Condottieri-class light cruiser, which served in the Regia Marina during World War II; named after Italian Field Marshal Luigi Cadorna who was commander in Chief of the Italian Army during World War I.

Luigi di Savoia Duca degli Abruzzi was an Italian Duca degli Abruzzi-class light cruiser, which served in the Regia Marina during World War II. After the war, she was retained by the Marina Militare and decommissioned in 1961. She was built by OTO at La Spezia and named after Prince Luigi Amedeo, Duke of the Abruzzi, an Italian explorer and Admiral of World War I.

The Battle of the Cigno Convoy was a naval engagement between two British destroyers of the Royal Navy and two torpedo boats of the Regia Marina south-east of Marettimo island to the west of Sicily, in the early hours of 16 April 1943. The Italian ships were escorting the transport ship Belluno to Tunisia; the torpedo boat Tifone, carried aviation fuel. The British force was fought off by the Italian ships for the loss of a torpedo boat. A British destroyer, disabled by Italian gunfire, had to be scuttled after the action when it was clear that it could not make port before dawn.

Baionetta was a Gabbiano-class corvette of the Regia Marina. She served in World War II from 1943 to 1945.

The Gufo radar (Owl) was an Italian naval search radar developed during World War II by the Regio Istituto Elettrotecnico e delle Comunicazioni della Marina (RIEC). Also known as the EC-3 ter.

Guichen has been the name of a number of ships of the French Navy named in honour of Luc Urbain de Bouëxic, comte de Guichen:

Operation Scylla was the transit of the Regia Marina Capitani Romani-class light cruiser Scipione Africano on the night of 17/18 July 1943, during the Second World War. The cruiser sailed from La Spezia in the Tyrrhenian Sea to Taranto in the Ionian Sea during the Allied invasion of Sicily.

Giovanni Galati was an Italian admiral during World War II. During the war, he commanded the Ugolino Vivaldi and participated in the Battle of Calabria. He became Chief of Staff of the Naval High Command Libya and was then, again, given command of the 14th Destroyer Squadron and then the Light Cruisers Group. He refused to surrender his ship when the armistice was agreed and was brought up on charges but eventually released and reinstated to active duty. He finished his service as Vice Admiral in 1947 and was awarded the Knight's Cross of the Military Order of Italy.

Bruto Brivonesi was an Italian admiral during World War II.

Zeffiro was one of eight Turbine-class destroyer built for the Regia Marina during the 1920s. She was named after a westerly wind, Zeffiro, common in summer in the Mediterranean. The ship played a minor role in the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1937, supporting the Nationalists.

Freccia was the lead ship of her class of four destroyers built for the Regia Marina in the early 1930s. Completed in 1931, she served in World War II and previous conflicts.

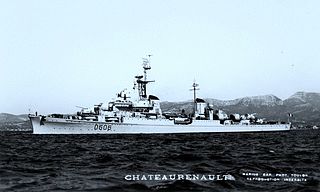

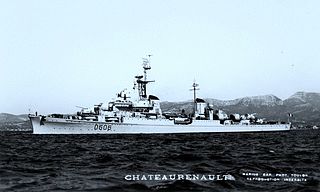

Chateaurenault was a French Capitani Romani-class light cruiser, acquired as war reparations from Italy in 1947 which served in the French Navy from 1948 to 1961. She was named in honour of François Louis de Rousselet, Marquis de Châteaurenault. In Italian service, the ship was named Attilio Regolo after Marcus Atilius Regulus the Roman statesman and general who was a consul of the Roman Republic in 267 BC and 256 BC.

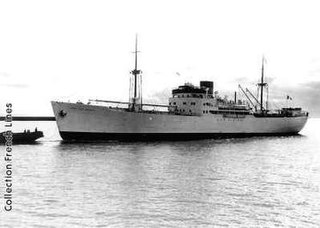

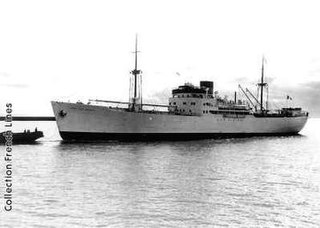

Barletta was an Italian cargo liner built during the 1930s and later became an auxiliary cruiser of the Regia Marina during World War II.