Related Research Articles

Freetown is the capital and largest city of Sierra Leone. It is a major port city on the Atlantic Ocean and is located in the Western Area of the country. Freetown is Sierra Leone's major urban, economic, financial, cultural, educational and political centre, as it is the seat of the Government of Sierra Leone. The population of Freetown was 1,055,964 at the 2015 census.

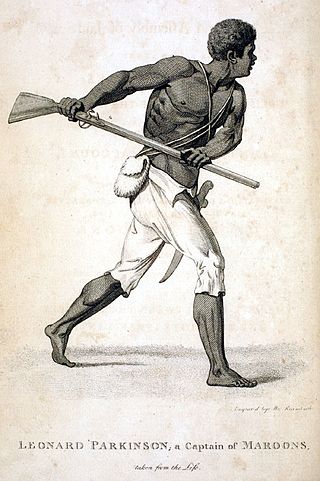

Maroons are descendants of Africans in the Americas and Islands of the Indian Ocean who escaped from slavery, through flight or manumission, and formed their own settlements. They often mixed with indigenous peoples, eventually evolving into separate creole cultures such as the Garifuna and the Mascogos.

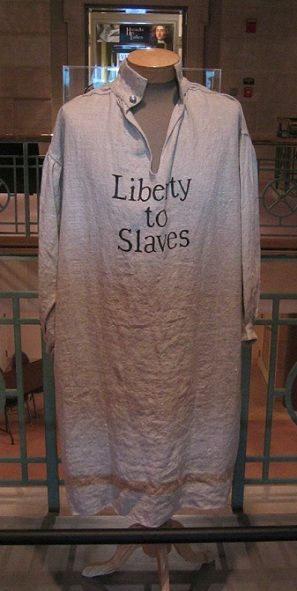

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the Crown's guarantee of freedom.

The Second Maroon War of 1795–1796 was an eight-month conflict between the Maroons of Cudjoe's Town, a Maroon settlement later renamed after Governor Edward Trelawny at the end of First Maroon War, located near Trelawny Parish, Jamaica in the St James Parish, and the British colonials who controlled the island. The Windward communities of Jamaican Maroons remained neutral during this rebellion and their treaty with the British still remains in force. Accompong Town, however, sided with the colonial militias, and fought against Trelawny Town.

St. John's Maroon Church is a Methodist church located in Maroon Town, a district of Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone. It is one of the oldest churches in the country.

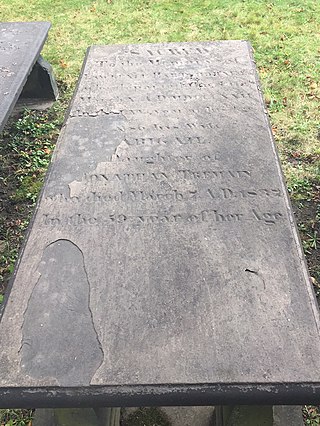

Black Nova Scotians are an ethnic group consisting of Black Canadians whose ancestors primarily date back to the Colonial United States as slaves or freemen, later arriving in Nova Scotia, Canada, during the 18th and early 19th centuries. As of the 2021 Census of Canada, 28,220 Black people live in Nova Scotia, most in Halifax. Since the 1950s, numerous Black Nova Scotians have migrated to Toronto for its larger range of opportunities. The first recorded free African person in Nova Scotia, Mathieu da Costa, a Mikmaq interpreter, was recorded among the founders of Port Royal in 1604. West Africans escaped slavery by coming to Nova Scotia in early British and French Colonies in the 17th and 18th centuries. Many came as enslaved people, primarily from the French West Indies to Nova Scotia during the founding of Louisbourg. The second major migration of people to Nova Scotia happened following the American Revolution, when the British evacuated thousands of slaves who had fled to their lines during the war. They were given freedom by the Crown if they joined British lines, and some 3,000 African Americans were resettled in Nova Scotia after the war, where they were known as Black Loyalists. There was also the forced migration of the Jamaican Maroons in 1796, although the British supported the desire of a third of the Loyalists and nearly all of the Maroons to establish Freetown in Sierra Leone four years later, where they formed the Sierra Leone Creole ethnic identity.

Jamaican Maroons descend from Africans who freed themselves from slavery on the Colony of Jamaica and established communities of free black people in the island's mountainous interior, primarily in the eastern parishes. Africans who were enslaved during Spanish rule over Jamaica (1493–1655) may have been the first to develop such refugee communities.

Major John Jarrett was a Jamaican Maroon leader of the Maroons of Cudjoe's Town in Jamaica. He was most likely named after a neighbouring planter with a similar surname.

Maroon Town, Sierra Leone, is a district in the settlement of Freetown, a colony founded in West Africa by Great Britain.

Cline Town is an area in Freetown, Sierra Leone. The area is named for Emmanuel Kline, a Hausa Liberated African who bought substantial property in the area. The neighborhood is in the vicinity of Granville Town, a settlement established in 1787 and re-established in 1789 prior to the founding of the Freetown settlement on 11 March 1792.

The Nova Scotian Settlers, or Sierra Leone Settlers, were African Americans who founded the settlement of Freetown, Sierra Leone and the Colony of Sierra Leone, on March 11, 1792. The majority of these black American immigrants were among 3,000 African Americans, mostly former slaves, who had sought freedom and refuge with the British during the American Revolutionary War, leaving rebel masters. They became known as the Black Loyalists. The Nova Scotian Settlers were jointly led by African American Thomas Peters, a former soldier, and English abolitionist John Clarkson. For most of the 19th century, the Settlers resided in Settler Town and remained a distinct ethnic group within the Freetown territory, tending to marry among themselves and with Europeans in the colony.

Maroon Town is a settlement in Jamaica. It has a population of 3122 as of 2009.

The Crown Colony of Jamaica and Dependencies was a British colony from 1655, when it was captured by the English Protectorate from the Spanish Empire. Jamaica became a British colony from 1707 and a Crown colony in 1866. The Colony was primarily used for sugarcane production, and experienced many slave rebellions over the course of British rule. Jamaica was granted independence in 1962.

Nancy Gardner Prince was an African-American woman born free in Newburyport, Massachusetts, She wrote about her travels in Russia and Jamaica during the nineteenth century in her autobiography titled A Narrative of The Life And Travels of Mrs. Nancy Prince, published in 1850.

The Sierra Leone Creole people are an ethnic group of Sierra Leone. The Sierra Leone Creole people are descendants of freed African-American, Afro-Caribbean, and Liberated African slaves who settled in the Western Area of Sierra Leone between 1787 and about 1885. The colony was established by the British, supported by abolitionists, under the Sierra Leone Company as a place for freedmen. The settlers called their new settlement Freetown. Today, the Sierra Leone Creoles are 1.2 percent of the population of Sierra Leone.

Arthur Thomas Daniel Porter III was a Creole professor, historian, and author. His book on the Sierra Leone Creole people, Creoledom: A study of the development of Freetown society, examines their society in a way in which few books of their time period had, and it is one of the most quoted books on the Creoles. He was published in East Africa and the UK.

Cudjoe's Town was located in the mountains in the southern extremities of the parish of St James, close to the border of Westmoreland, Jamaica.

Montague James was a Maroon leader of Cudjoe's Town in the last decade of eighteenth-century Jamaica. It is possible that Maroon colonel Montague James took his name from the white superintendent of Trelawny Town, John Montague James.

Charles Samuels was a maroon officer from Cudjoe's Town, and he was the brother of Captain Andrew Smith. Both officers reported to Colonel Montague James, the leader of Trelawny Town.

Andrew Smith was a Maroon officer from Cudjoe's Town. His brother, Charles Samuels, was also an officer from Trelawny Town, and both officers reported to Colonel Montague James.

References

- ↑ Mavis Campbell, The Maroons of Jamaica (Massachusetts: Bergin & Garvey, 1988), pp. 209–49.

- ↑ Grant, John. Black Nova Scotians. Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Museum, 1980.

- ↑ The African in Canada ; the Maroons of Jamaica and Nova Scotia [microform]. 1890. ISBN 9780665053481.

- ↑ Robin Winks, The Blacks in Canada (Montreal: McGill University, 1997), pp. 82–83.

- ↑ Grant, John N. (2002). The Maroons in Nova Scotia. Halifax: Formac. pp. 20–33.

- ↑ Michael Siva, After the Treaties: A Social, Economic and Demographic History of Maroon Society in Jamaica, 1739–1842, PhD Dissertation (Southampton: Southampton University, 2018), p. 145.

- ↑ R.C. Dallas, "The History of the Maroons" (1803), Vol. 2, p. 256.

- ↑ Grant, John N (2002). The Maroons in Nova Scotia (Softcover). Formac. p. 203. ISBN 978-0887805691.

- ↑ Simon Schama, Rough Crossings (London: BBC Books, 2002), p. 382.

- ↑ Mavis Campbell, Back to Africa: George Ross and the Maroons (Trenton: Africa World Press, 1993), p. 48.

- ↑ James Walker, The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone 1783–1870 (London: Longman, 1976), pp. 272, 277–80.

- ↑ John Grant, The Maroons in Nova Scotia (Halifax: Formac, 2002), p. 150.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 17.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 17.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), pp. 17-18.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 18.

- ↑ James Walker, The Black Loyalists: The Search for a Promised Land in Nova Scotia and Sierra Leone 1783-1870 (London: Longman, 1976), pp. 240-3.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 17.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 18.

- ↑ Fortin (2006), p. 23.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), p. 18.

- ↑ Michael Sivapragasam, "The Returned Maroons of Trelawny Town", Navigating Crosscurrents: Trans-linguality, Trans-culturality and Trans-identification in the Dutch Caribbean and Beyond, ed. by Nicholas Faraclas, etc (Curacao/Puerto Rico: University of Curacao, 2020), pp. 13, 18.

- ↑ "St. John's Maron (sic) Church". Monuments and Relics Commission. Archived from the original on February 16, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ Robert Baron and Ana C. Cara, Creolization as Cultural Creativity, University Press of Mississippi, 2011; accessed 12 July 2016, available online through Project MUSE