West Yorkshire is a metropolitan and ceremonial county in the Yorkshire and the Humber region of England. It borders North Yorkshire to the north and east, South Yorkshire and Derbyshire to the south, Greater Manchester to the south-west, and Lancashire to the west. The city of Leeds is the largest settlement.

Taxidermy is the art of preserving an animal's body by mounting or stuffing, for the purpose of display or study. Animals are often, but not always, portrayed in a lifelike state. The word taxidermy describes the process of preserving the animal, but the word is also used to describe the end product, which are called taxidermy mounts or referred to simply as "taxidermy".

Wortley is an inner city area of Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It begins one mile to the west of the city centre. The appropriate City of Leeds ward is called Farnley and Wortley.

James Rowland Ward (1848–1912) was a British taxidermist and founder of the firm Rowland Ward Limited of Piccadilly, London. The company specialised in and was renowned for its taxidermy work on birds and big-game trophies, but it did other types of work as well. In creating many practical items from antlers, feathers, feet, skins, and tusks, the Rowland Ward company made fashionable items from animal parts, such as zebra-hoof inkwells, antler furniture, and elephant-feet umbrella stands.

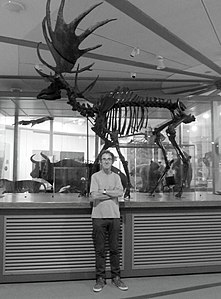

Leeds City Museum, originally established in 1819, reopened in 2008 in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. It is housed in the former Mechanics' Institute built by Cuthbert Brodrick, in Cookridge Street. It is one of nine sites in the Leeds Museums & Galleries group.

Warrington Museum & Art Gallery is on Bold Street in the Cultural Quarter of Warrington in a Grade II listed building that it shares with the town's Central Library. The Museum and the Library originally opened in 1848 as the first rate-supported library in the UK, before moving to their current premises in 1858. The art galleries were subsequently added in 1877 and 1931. Operated by Culture Warrington, Warrington Museum and Art Gallery has the distinction of being one of the oldest municipal museums in the UK and much of the quintessential character of the building has been preserved.

Martha Ann Maxwell was an American naturalist, artist and taxidermist. She helped found modern taxidermy. Maxwell's pioneering diorama displays are said to have influenced major figures in taxidermy history who entered the field later, such as William Temple Hornaday and Carl Akeley. She was born in Pennsylvania in 1831. Among her many accomplishments, she is credited with being the first woman field naturalist to obtain and prepare her own specimens. She was inducted into the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame in 1985.

David James Schwendeman was an American taxidermist. Schwendeman was the last, full-time chief taxidermist for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, serving in that position for twenty-nine years from 1959 until his retirement in 1988. Schwendeman was responsible for mounting and designing many of the specimens on display in the museum, including the collections in the Hall of North American Animals, the Hall of North American Birds, and the Hall of Reptiles and Amphibians.

Polly Morgan is a London-based British artist who uses taxidermy to create works of art.

The conservation and restoration of fur objects is the preservation and protection of objects made from or containing fur. These pieces can include personal items like fur clothing or objects of cultural heritage that are housed in museums and collections. When dealing with the latter, a conservator-restorer often handles their care, whereas, for the public, professional furriers can be found in many neighborhoods.

The conservation of taxidermy is the ongoing maintenance and preservation of zoological specimens that have been mounted or stuffed for display and study. Taxidermy specimens contain a variety of organic materials, such as fur, bone, feathers, skin, and wood, as well as inorganic materials, such as burlap, glass, and foam. Due to their composite nature, taxidermy specimens require special care and conservation treatments for the different materials.

Tocher and Tocher were a firm of Anglo Indian taxidermists located in Bangalore, India. William Tocher was born in India in 1853 and was of Scottish ancestry. William’s father, James, had arrived in India with the East India Company. William became involved in taxidermy as a hobby; he later started his own taxidermy business in 1906.

Sinclair Nathaniel Clark was a legendary taxidermy tanner, known throughout that industry for his expertise in tanning animal skins to give them the suppleness that taxidermists require to create lifelike, long-lasting displays. Tanning is the process of treating animal skins and hides for display and preservation. Because tanning is a behind-the-scenes operation of taxidermy, tanners are seldom known outside the industry.

Jane Yandle was a professional furrier and taxidermist noted for her taxidermy of New Zealand birds, some of which are still on museum display more than 100 years after her death.

The Leeds Tiger is a taxidermy-mounted 19th-century Bengal tiger, displayed at Leeds City Museum in West Yorkshire, England. It has been a local visitor attraction for over 150 years.

William Gott, was a British wool merchant, mill owner, philanthropist towards public services and art collector from Leeds, West Riding of Yorkshire, England.

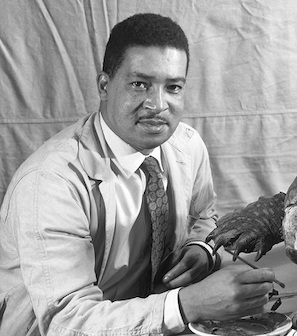

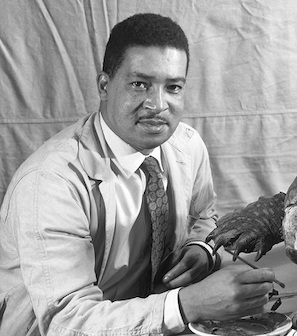

Carl Cotton (1918–1971) was an American taxidermist known for his work on exhibition development at the Field Museum of Natural History from 1947 to 1971. He was the first African American taxidermist at the Field Museum and, as noted by museum staff, likely the first professional black taxidermist in all of Chicago.

The Armley Hippo, previously known as the Leeds Hippopotamus, is a partial skeleton of a common hippopotamus consisting of 122 bones, of which 25 were taxidermy-mounted in 2008 by James Dickinson for display at Leeds City Museum in Leeds, West Yorkshire, England. The skeleton dates to the last interglacial (Eemian) around 130,000 to 115,000 years ago.

Harry Ferris Brazenor was a British taxidermist. He was known especially for his work for Manchester and Salford museums, besides other institutions in Northern England. At Manchester Museum he was recognised for his taxidermy-mounted sperm whale skeleton, giraffe, polar bear, and a wolf with painted "blood" on its teeth. His work for Salford Museum included an Asian elephant displayed next to a tiny shrew. His Salford tiger was transferred to Leeds City Museum and is still displayed there. For Hancock Museum at Newcastle upon Tyne he mounted a bison bull, and for the former Belle Vue Zoological Gardens he mounted an Indian rhinoceros.