The history of Slovenia chronicles the period of the Slovenian territory from the 5th century BC to the present. In the Early Bronze Age, Proto-Illyrian tribes settled an area stretching from present-day Albania to the city of Trieste. The Slovenian territory was part of the Roman Empire, and it was devastated by the Migration Period's incursions during late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages. The main route from the Pannonian plain to Italy ran through present-day Slovenia. Alpine Slavs, ancestors of modern-day Slovenians, settled the area in the late 6th Century AD. The Holy Roman Empire controlled the land for nearly 1,000 years. Between the mid-14th century through 1918 most of Slovenia was under Habsburg rule. In 1918, most Slovene territory became part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes, and in 1929 the Drava Banovina was created within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia with its capital in Ljubljana, corresponding to Slovenian-majority territories within the state. The Socialist Republic of Slovenia was created in 1945 as part of federal Yugoslavia. Slovenia gained its independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, and today it is a member of the European Union and NATO.

"Zdravljica" is a carmen figuratum poem by the 19th-century Romantic Slovene poet France Prešeren, inspired by the ideals of Liberté, égalité, fraternité. It was written in 1844 and published with some changes in 1848. Four years after it was written, Slovenes living within Habsburg Empire interpreted the poem in spirit of the 1848 March Revolution as political promotion of the idea of a united Slovenia. In it, the poet also declares his belief in a free-thinking Slovene and Slavic political awareness. In 1989, it was adopted as the regional anthem of Slovenia, becoming the national anthem upon independence in 1991.

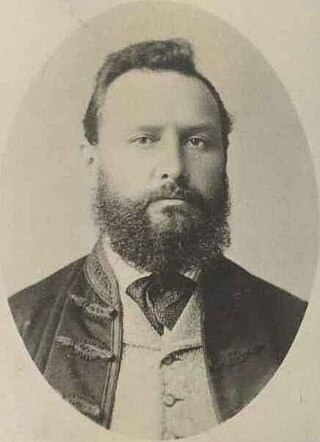

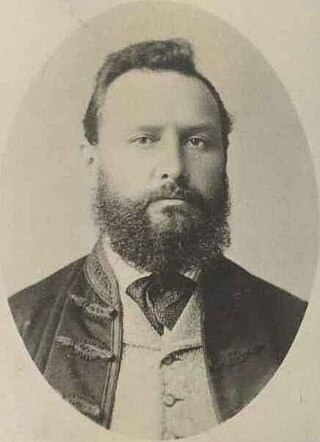

Fran Levstik was a Slovene writer, political activist, playwright and critic. He was one of the most prominent exponents of the Young Slovene political movement.

United Slovenia is the name originally given to an unrealized political programme of the Slovene national movement, formulated during the Spring of Nations in 1848. The programme demanded (a) unification of all the Slovene-inhabited areas into one single kingdom under the rule of the Austrian Empire, (b) equal rights of Slovene in public, and (c) strongly opposed the planned integration of the Habsburg monarchy with the German Confederation. The programme failed to meet its main objectives, but it remained the common political program of all currents within the Slovene national movement until World War I.

Ivan Tavčar was a Slovenian writer, lawyer, and politician.

Navje Memorial Park, the redesigned part of the former St. Christopher's Cemetery, is a memorial park in Ljubljana, the capital of Slovenia. It is located in the Bežigrad district, just behind the Ljubljana railway station.

Davorin Trstenjak was a Slovene writer, historian and Roman Catholic priest.

The Slovene Society is the second-oldest publishing house in Slovenia, founded on 4 February 1864 as an institution for the scholarly and cultural progress of Slovenes.

Janez Evangelist Krek was a Slovene Christian Socialist politician, priest, journalist, and author.

Lovro Toman was a Slovene Romantic nationalist revolutionary activist during the Revolution of 1848, known as the person who in Ljubljana, at the Wolf Street 8, raised the Slovene tricolor for the first time in history in response to a German flag raised on top of the Ljubljana Castle. Later he helped founding one of the first Slovene publishing houses, the Slovenska matica. He was a Slovene national conservative politician and member of the Austrian Parliament. Together with Janez Bleiweis and Etbin Henrik Costa, he was part of the leadership of the Old Slovene party.

Albin Prepeluh was a Slovenian left wing politician, journalist, editor, political theorist and translator. Before World War I, he was the foremost Slovene Marxist revisionist theoretician. After the War, he became one of the most persistent advocates of Slovenian autonomy within the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, and, together with Dragotin Lončar, the ideologist of the democratic reformist faction of Slovenian Social Democrats. In the late 1920s, he evolved towards agrarianism. He was also known under the pseudonym Abditus.

Dragotin Lončar was a Slovenian historian, editor, and Social Democratic politician.

Karel Dežman, also known as Dragotin Dežman and Karl Deschmann, was a Carniolan liberal politician and natural scientist. He was one of the most prominent personalities of the political, cultural, and scientific developments in the 19th-century Duchy of Carniola. He is considered one of the fathers of modern archeology in what is today Slovenia. He also made important contributions in botany, zoology, mineralogy, geology and mineralogy. He was the first director of the Provincial Museum of Carniola, now the National Museum of Slovenia. Due to his switch from Slovene liberal nationalism to Austrian centralism and pro-German cultural stances, he became a symbol of national renegadism.

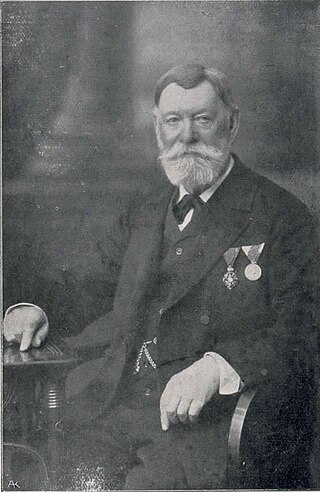

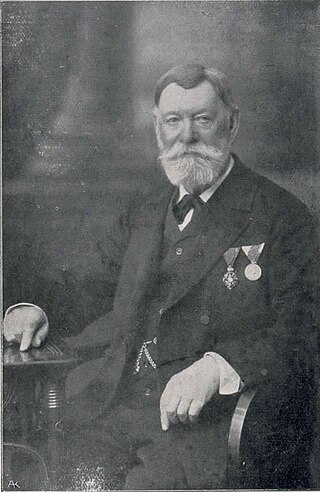

Josip Vošnjak was a Slovene politician and author, leader of the Slovene National Movement in the Duchy of Styria, one of the most prominent representatives of the Young Slovene movement.

Etbin Henrik Costa was a Slovene national conservative politician and author. Together with Janez Bleiweis and Lovro Toman, he was one of the leaders of the Old Slovene political party.

Young Slovenes were a Slovene national liberal political movement in the 1860s and 1870s, inspired and named after the Young Czechs in Bohemia and Moravia. They were opposed to the national conservative Old Slovenes. They entered a crisis in the 1880s, and disappeared from Slovene politics by the 1890s. They are considered the precursors of Liberalism in Slovenia.

Old Slovenes is the term used for a national conservative political group in the Slovene Lands from the 1850s to the 1870s, which was opposed to the radical national liberal Young Slovenes. The main Old Slovene leaders were Janez Bleiweis, Lovro Toman, Luka Svetec, Etbin Henrik Costa, and Andrej Einspieler.

Engelbert Besednjak was a Slovene Christian Democrat politician, lawyer and journalist. In the 1920s, he was one of the leaders of the Slovene and Croat minority in the Italian-administered Julian March. In the 1930s, he was one of the leaders of Slovene anti-Fascist émigrés from the Slovenian Littoral, together with Josip Vilfan, Ivan Marija Čok and Lavo Čermelj.

Janko Kersnik was a writer and politician from Austria-Hungary who was an ethnic Slovene. Together with Josip Jurčič, he is considered the most important representative of literary realism in the Slovene language.

Luka Svetec was a Slovene politician, lawyer, author and philologist. In the 1870s and 1880s, Svetec was one of the most influential leaders of the so-called Old Slovenes, a national conservative political group in 19th century Slovene Lands. He was renowned as an honest and principled politician, and was praised for his decency and his straightforward, practical attitude to political questions and life in general. The Old Slovene leader Janez Bleiweis called him "a crystallized Slovene common sense". Because of his failure to take over the political leadership of the party after the death of its leader Janez Bleiweis, also called Father of the Nation, Svetec was mockingly referred in the press to as "Stepfather of the Nation".