Related Research Articles

Safaitic is a variety of the South Semitic scripts used by the Arabs in southern Syria and northern Jordan in the Ḥarrah region, to carve rock inscriptions in various dialects of Old Arabic and Ancient North Arabian. The Safaitic script is a member of the Ancient North Arabian (ANA) sub-grouping of the South Semitic script family, the genetic unity of which has yet to be demonstrated.

Ancient North Arabian (ANA) is a collection of scripts and a language or family of languages under the North Arabian languages branch along with Old Arabic that were used in north and central Arabia and south Syria from the 8th century BCE to the 4th century CE. The term "Ancient North Arabian" is defined negatively. It refers to all of the South Semitic scripts except Ancient South Arabian (ASA) regardless of their genetic relationships.

Christianity was one of the prominent monotheistic religions of pre-Islamic Arabia. Christianization emerged as a major phenomena in the Arabian peninsula during the period of late antiquity, especially from the north due to the missionary activities of Syrian Christians and the south due to the entrenchment of Christianity with the Aksumite conquest of South Arabia. Christian communities had already surrounded the peninsula from all sides prior to their spread within the region. Sites of Christian organization such as churches, martyria and monasteries were built and formed points of contact with Byzantine Christianity as well as allowed local Christian leaders to display their benefaction, communicate with the local population, and meet with various officials. At present, it is believed that Christianity had attained a significant presence in Arabia by the fifth century at the latest, that its largest presence was in Southern Arabia (Yemen) prominently including the city of Najran, and that the Eastern Arab Christian community communicated with the Christianity of the Levant region through Syriac.

Old Arabic is the name for any Arabic language or dialect continuum before Islam. Various forms of Old Arabic are attested in scripts like Safaitic, Hismaic, Nabatean, and even Greek.

Harran is a village in the as-Suwayda Governorate in southwestern Syria. It is situated in the southern Lajah plateau, northwest of the city of as-Suwayda. Harran had a population of 1,523 in the 2004 census.

Nabataean Arabic was a predecessor of the Arabic alphabet. It evolved from Nabataean Aramaic, first entering use in the late third century AD. It continued to be used into the mid-fifth century, after which the script evolves into a new phase known as Paleo-Arabic.

Jabal Sais (Arabic: جبل سايس also known as Qasr Says is a Umayyad desert fortification or former palace in Syria which was built 707-715 AD. The fortification sits near an extinct volcano. Jabal Says is mountain peak next to the fortification which sits 621 meters above sea level.

The Jabal Ḏabūbinscription is a South Arabian graffito inscription composed in a minuscule variant of the late Sabaic language and dates to the 6th century, notable for the appearance of a pre-Islamic variant of the Basmala. It was found on a rocky facade at the top of the eastern topside of mount Thaboob in the Dhale region of Yemen and first published in 2018 by M.A. Al-Hajj and A.A. Faqʿas.

The Rīʿ al-Zallālah inscription is a pre-Islamic Paleo-Arabic inscription, likely dating to the 6th century, located near Taif, in a narrow pass that connects this city to the al-Sayl al- Kabīr wadi.

The Rūwafa inscriptions are a group of five Greek–Nabataean Arabic inscriptions known from the isolated Ruwāfa temple, located in the Hisma desert of Northwestern Arabia, or roughly 200 km northwest of Hegra. They are dated to 165–169 AD. The inscriptions are numbered using Roman numerals, running from Inscriptions I to Inscription V. Two of the five inscriptions describe the structure as a temple and that it was constructed by the εθνος/šrkt of Thamud in honor of the emperors Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus. The Thamud tribe is otherwise well-attested to have existed in this region of Arabia from at least the 8th century BC. At the time of the composition of these inscriptions in the second century, northwestern Arabia was known as Arabia Petraea, a frontier province of the Roman Empire that had been previously conquered in 106 AD.

The Zabad inscription is a trilingual Christian inscription containing text in the Greek, Syriac, and Paleo-Arabic scripts. Composed in the village of Zabad in northern Syria in 512, the inscription dedicates the construction of the martyrium, named the Church of St. Sergius, to Saint Sergius. The inscription itself is positioned at the lintel of the entrance portal.

The Harrān inscription is an Arabic-Greek bilingual Christian dedicatory at a martyrium in the Harran village, which is in the city of as-Suwayda in Syria. It dates to 567–568.

Paleo-Arabic is a script that represents a pre-Islamic phase in the evolution of the Arabic script at which point it becomes recognizably similar to the Islamic Arabic script. It comes prior to Classical Arabic, but it is also a recognizable form of the Arabic script, emerging after a transitional phase of Nabataean Arabic as the Nabataean script slowly evolved into the modern Arabic script. It appears in the late fifth and sixth centuries AD and, though was originally only known from Syria and Jordan, is now also attested in several extant inscriptions from the Arabian Peninsula, such as in the Christian texts at the site of Hima in South Arabia. More recently, additional examples of Paleo-Arabic have been discovered near Taif in the Hejaz and in the Tabuk region of northwestern Saudi Arabia.

The Yazīd inscription is an early Christian Paleo-Arabic rock carving from the region of as-Samrūnīyyāt, 12 km southeast of Qasr Burqu' in the northeastern Jordan.

The Ḥimà Paleo-Arabic inscriptions are a group of twenty-five inscriptions discovered at Hima, 90 km north of Najran, in southern Saudi Arabia, written in the Paleo-Arabic script. These are among the broader group of inscriptions discovered in this region and were discovered during the Saudi-French epigraphic mission named the Mission archéologique franco-saoudienne de Najran. They were the first Paleo-Arabic inscriptions discovered in Saudi Arabia, before which examples had only been known from Syria. The inscriptions have substantially expanded the understanding of the evolution of the Arabic script.

The Dūmat al-Jandal inscription is an Arabic Christian graffito written in the Paleo-Arabic script, and discovered at the Arabian site of Dumat al-Jandal. It was carved into the middle-left of a sandstone bolder, above a Nabataean Arabic inscription found a little lower. The rock also contains drawings of four female camels, one male camel, and an ibex.

The Umm al-Jimāl inscription is an undated Paleo-Arabic inscription from Umm al-Jimal in the Hauran region of Jordan. It is located on the pillars base of a basalt slab in the northern part of the "Double Church" at the site of Umm al-Jimal and was partly covered with plaster on discovery.

The Umm Burayrah inscription is a Paleo-Arabic inscription discovered in the Tabuk Province of northwestern Saudi Arabia. Among Paleo-Arabic inscriptions it contains a unique invocation formula, a prayer for forgiveness, and the personal name ʿAbd Shams. It was originally photographed and published by Muhammed Abdul Nayeem in 2000, and was recently redocumented by the amateur archaeologist Saleh al‐Hwaiti.

The practice of polytheistic religion dominated in pre-Islamic Arabia until the fourth century. Inscriptions in various scripts used in the Arabian Peninsula including the Nabataean script, Safaitic, and Sabaic attest to the practice of polytheistic cults and idols until the fourth century, whereas material evidence from the fifth century onwards is almost categorically monotheistic. It is in this era that Christianity, Judaism, and other generic forms of monotheism become salient among Arab populations. In South Arabia, the ruling class of the Himyarite Kingdom would convert to Judaism and a cessation of polytheistic inscriptions is witnessed. Monotheistic religion would continue as power in this region transitioned to Christian rulers, principally Abraha, in the early sixth century.

Ahmad Al-Jallad is a Jordanian-American philologist, epigraphist, and a historian of language. Some of the areas he has contributed to include Quranic studies and the history of Arabic, including recent work he has done on the Safaitic and Paleo-Arabic scripts. He is currently Professor in the Sofia Chair in Arabic Studies at Ohio State University at the Department of Near Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures. He is the winner of the 2017 Dutch Gratama Science Prize.

References

- ↑ Al‐Jallad, Ahmad; Sidky, Hythem (2022). "A Paleo‐Arabic inscription on a route north of Ṭāʾif". Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 33 (1): 202–215. doi:10.1111/aae.12203. ISSN 0905-7196.

- ↑ Grasso, Valentina A. (2023). Pre-islamic Arabia: societies, politics, cults and identities during late antiquity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 151–152. ISBN 978-1-009-25296-6.

- ↑ Fiema, Zbigniew T.; al-Jallad, Ahmad; MacDonald, Michael C.A.; Nehmé, Laila (2015). "Provincia Arabia: Nabataea, the Emergence of Arabic as a Written Language, and Graeco-Arabica". In Fisher, Greg (ed.). Arabs and empires before Islam. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 412–413. ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.

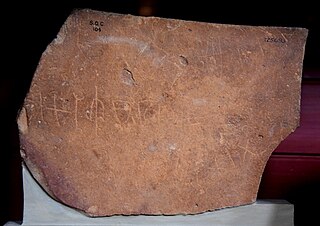

- ↑ M.C.A., MacDonald (2010). "The Old Arabic graffito at Jabal Usays: A new reading of line 1". In MacDonald, M.C.A. (ed.). The Development of Arabic as a Written Language. Archaeopress. pp. 141–143.

- 1 2 Fisher, Greg (2020). Rome, Persia, and Arabia: shaping the Middle East from Pompey to Muhammad. London New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 128, 140. ISBN 978-0-415-72880-5.

- ↑ Abū ʾl-Faraj al-ʿUshsh, Muḥammad (1964). "Kitabat ʿArabiyya Ghayr Manshura fi Jabal Usays". Al-Abhhath. 17: 227–316.

- 1 2 3 Larcher, Pierre (2010). "In search of a standard: dialect variation and New Arabic features in the oldest Arabic written documents". Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies. 40: 103–112. ISSN 0308-8421.

- ↑ Genequand, Denis (2015). "The Archaeological Evidence for the Jafnisa and the Naṣrids". In Fisher, Greg (ed.). Arabs and empires before Islam. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. pp. 175–193. ISBN 978-0-19-965452-9.