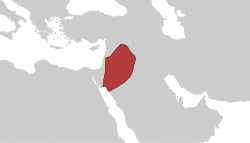

Rashidun conquest of the Levant

The nascent Muslim state in Medina, first under the Islamic prophet Muhammad (d. 632) and lastly under the second caliph, Umar (r. 634–644), made abortive attempts to contact or win over the Ghassan of Syria. The last phylarch of the Ghassan, Jabala ibn al-Ayham, stories of whom are shrouded in legend, led his tribesmen and those of Byzantium's other allied Arab tribes in the Byzantine army that was routed by the Muslims at the Battle of Yarmouk in c. 636. After supposedly embracing Islam, Jabala left the faith and ultimately withdrew with his tribesmen from Syria to Byzantine-held Anatolia in 639, by which time the Muslims had conquered most of Byzantine Syria. Unable to make headway with the Ghassan, the Muslim administration in Syria under its governor Mu'awiya succeeded in allying with the Ghassan's old-established Syrian allies, the Banu Kalb. The latter became the cornerstone of Mu'awiya's military power in Syria, and later, when he became head of the Syria-based Umayyad Caliphate in 661, of the Islamic empire in general.

Umayyad and Abbasid periods

Significant remnants of the Ghassan remained in Syria, residing in Damascus and the city's Ghouta countryside. At least nominally and probably gradually, many of these Ghassanids embraced Islam, especially under Mu'awiya's rule. According to the historian Nancy Khalek, they consequently became an "indispensable" group of Muslim society in early Islamic Syria. Mu'awiya actively sought the militarily and administratively experienced Syrian Christians, including the Ghassanids, and members of the tribe served him and later Umayyad caliphs as governors, commanders of the shurta (select troops), scribes, and chamberlains. Several descendants of the tribe's Tha'laba and Imru al-Qays branches are listed in the sources as Umayyad court poets, jurists, and officials in the eastern provinces of Khurasan, Adharbayjan and Armenia.

When Mu'awiya's grandson, Caliph Mu'awiya II, died without a chosen successor amid the Second Muslim Civil War in 684, Umayyad rule was on the verge of collapse in Syria, having already collapsed throughout the caliphate, where the supporters of a rival caliph, the Mecca-based Ibn al-Zubayr, took charge. The Ghassan, along with their tribal allies in Syria, especially the Kalb, supported continued Umayyad rule to secure their interests under the dynasty, and nominated Mu'awiya's distant cousin, Marwan I, as caliph during a summit of the Syrian tribes in the old Ghassanid capital of Jabiyah. Dahhak ibn Qays al-Fihri, the governor of Damascus, meanwhile, threw his backing behind Ibn al-Zubayr. During the Battle of Marj Rahit, which pitted Marwan against Dahhak in a meadow north of Damascus, the scion of the Ghassanid family in Damascus, Yazid ibn Abi al-Nims, led a revolt there and secured control of the city for Marwan, who routed Dahhak and assumed office. In a poem attributed to him, Marwan lauds the Ghassan, as well as the Kalb, Kinda, and Tanukh of Syria, for supporting him.

The above tribes thereafter formed the Yaman faction, in opposition to the Qays tribes which backed Dahhak and Ibn al-Zubayr. The Qays–Yaman rivalry contributed to the downfall of Umayyad rule, with each faction supporting different Umayyad dynasts and governors in what became the Third Muslim Civil War. The Ghassanid Shabib ibn Abi Malik was a leader of the Yaman in Damascus and conspired to assassinate the pro-Qaysi Caliph al-Walid II (r. 743–744). After the latter was killed, the Ghassan marched on Damascus to help install his successor, the Yamani-backed Yazid III (r. 744–744). The toppling of the Umayyads and the advent of the Iraq-based Abbasid Caliphate in 750 "was disastrous for the power, wealth and status of the Arab tribes in Syria", including the Ghassan, according to the historian Hugh N. Kennedy. By the 9th century, the tribe had adopted a settled life, being recorded by the geographer al-Ya'qubi (d. 890) to be living in the Ghouta gardens region of Damascus and in Gharandal in Transjordan.

Scholarly families in Damascus

Two Damascene Ghassanid families in particular achieved prominence in early Islamic Syria, those of Yahya ibn Yahya al-Ghassani (d. 750s) and Abu Mushir al-Ghassani (d. 833). The former was the son of Caliph Marwan's head of the shurta, Yahya ibn Qays. Upon returning to Damascus after his stint as a governor of Mosul for the Umayyad caliph Umar II (r. 717–720), Yahya ibn Yahya took up scholarship and became known as the sayyid ahl Dimashq (leader of the people of Damascus), transmitting purported hadiths (traditions and utterances) of Muhammad, which he derived from his uncle Sulayman, who received the transmissions from Muhammad's Damascus-based companion, Abu Darda. Among some traditions sourced to Yahya ibn Yahya by later Muslim scholars are those regarding the discovery of John the Baptist's head in the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus and others which praise the mosque's splendor and the Umayyad dynasty in general. Yahya ibn Yahya's sons, grandsons, great-grandsons and great-great-grandsons continued their ancestor's interests in hadith scholarship and remained part of the Damascene elite into the mid-9th century.

Abu Mushir's grandfather, Abd al-A'la, was a hadith scholar and Abu Mushir studied under the famous Syrian scholar Sa'id ibn Abd al-Aziz al-Tanukhi. He became a prominent hadith scholar in Damascus, with special interest in the administrative history of Syria, its local elite's genealogies and local scholars. During the Fourth Muslim Civil War between the Abbasid dynasts, an Umayyad, Abu al-Umaytir al-Sufyani, took power in Syria in 811, in a bid to reestablish the Umayyad Caliphate. Abu Mushir, whose grandfather was killed by the Abbasids in 750, disdained the Iraqis represented by the Abbasids and supported the restoration of Umayyad rule. He served as Abu al-Umaytir's qadi (chief jurist), but was imprisoned by the Abbasids in the years following the rebellion's suppression in 813. His great-grandsons Abd al-Rabb ibn Muhammad and Amr ibn Abd al-A'la also attained fame as Damascene scholars.