Eskimo is an exonym that refers to two closely related Indigenous peoples: Inuit and the Yupik of eastern Siberia and Alaska. A related third group, the Aleut, who inhabit the Aleutian Islands, are generally excluded from the definition of Eskimo. The three groups share a relatively recent common ancestor, and speak related languages belonging to the family of Eskaleut languages.

The Inuit languages are a closely related group of indigenous American languages traditionally spoken across the North American Arctic and the adjacent subarctic regions as far south as Labrador. The Inuit languages are one of the two branches of the Eskimoan language family, the other being the Yupik languages, which are spoken in Alaska and the Russian Far East. Most Inuit people live in one of three countries: Greenland, a self-governing territory within the Kingdom of Denmark; Canada, specifically in Nunavut, the Inuvialuit Settlement Region of the Northwest Territories, the Nunavik region of Quebec, and the Nunatsiavut and NunatuKavut regions of Labrador; and the United States, specifically in northern and western Alaska.

The Yupik are a group of Indigenous or Aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat. Yupik peoples include the following:

The Iñupiat are a group of Indigenous Alaskans whose traditional territory roughly spans northeast from Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the northernmost part of the Canada–United States border. Their current communities include 34 villages across Iñupiat Nunaat, including seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation. They often claim to be the first people of the Kauwerak.

The Thule or proto-Inuit were the ancestors of all modern Inuit. They developed in coastal Alaska by the year 1000 and expanded eastward across northern Canada, reaching Greenland by the 13th century. In the process, they replaced people of the earlier Dorset culture that had previously inhabited the region. The appellation "Thule" originates from the location of Thule in northwest Greenland, facing Canada, where the archaeological remains of the people were first found at Comer's Midden.

The Paleo-Eskimo were the peoples who inhabited the Arctic region from Chukotka in present-day Russia across North America to Greenland prior to the arrival of the modern Inuit (Eskimo) and related cultures. The first known Paleo-Eskimo cultures developed by 2500 BCE, but were gradually displaced in most of the region, with the last one, the Dorset culture, disappearing around 1500 CE.

An ulu is an all-purpose knife traditionally used by Inuit, Iñupiat, Yupik, and Aleut women. It is used in applications as diverse as skinning and cleaning animals, cutting a child's hair, cutting food, and sometimes even trimming blocks of snow and ice used to build an igloo.

Prehistoric Alaska begins with Paleolithic people moving into northwestern North America sometime between 40,000 and 15,000 years ago across the Bering Land Bridge in western Alaska; a date less than 20,000 years ago is most likely. They found their passage blocked by a huge sheet of ice until a temporary recession in the Wisconsin glaciation opened up an ice-free corridor through northwestern Canada, possibly allowing bands to fan out throughout the rest of the continent. Eventually, Alaska became populated by the Inuit and a variety of Native American groups. Trade with both Asia and southern tribes was active even before the advent of Europeans.

Dorothy Jean Ray was an author and anthropologist best known for her study of Native Alaskan art and culture.

James W. VanStone was an American cultural anthropologist specializing in the group of peoples then known as Eskimos. He studied at the University of Pennsylvania and was a student of Frank Speck and Alfred Irving Hallowell. One of his first positions was at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. In 1951, following completion of graduate studies, he joined the faculty of the Department of Anthropology at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. In 1955 and 1956, he conducted fieldwork with the Inuit at Point Hope, Alaska. Beginning in the summer of 1960, he started field work among Chipewyan Indians, living along the east shore of Great Slave Lake in Canada's Northwest Territories among eastern Athapaskans for a period of eleven months over three years. He died of heart failure.

Inuit art, also known as Eskimo art, refers to artwork produced by Inuit, that is, the people of the Arctic previously known as Eskimos, a term that is now often considered offensive. Historically, their preferred medium was walrus ivory, but since the establishment of southern markets for Inuit art in 1945, prints and figurative works carved in relatively soft stone such as soapstone, serpentinite, or argillite have also become popular.

Based on archeological finds, Brooman Point Village is an abandoned village in Qikiqtaaluk Region, Nunavut, Canada. It is located in the central High Arctic near Brooman Point of the Gregory Peninsula, part of the eastern coast of Bathurst Island. Brooman was both a Late Dorset culture Paleo-Eskimo village as well as an Early Thule culture village. Both the artifacts and the architecture, specifically longhouses, are considered important historical remains of the two cultures. The site shows traces of Palaeo-Eskimo occupations between about 2000 BC and 1 AD, but the major prehistoric settlement occurred from about 900 to 1200 AD.

Inuit are a group of culturally and historically similar Indigenous peoples traditionally inhabiting the Arctic and subarctic regions of North America, including Greenland, Labrador, Quebec, Nunavut, the Northwest Territories, Yukon (traditionally), Alaska, and Chukotsky District of Chukotka Autonomous Okrug, Russia. Inuit languages are part of the Eskimo–Aleut languages, also known as Inuit-Yupik-Unangan, and also as Eskaleut. Inuit Sign Language is a critically endangered language isolate used in Nunavut.

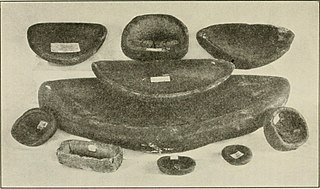

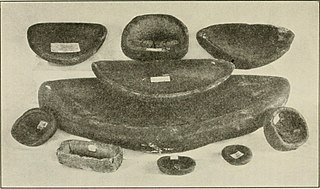

The qulliq, is the traditional oil lamp used by Arctic peoples, including the Inuit, the Chukchi and the Yupik peoples.

Margaret Lantis was an American anthropologist, Eskimologist, and writer.

Yup'ik doll is a traditional Eskimo style doll and figurine form made in the southwestern Alaska by Yup'ik people. Also known as Cup'ik doll for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig doll for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. Typically, Yup'ik dolls are dressed in traditional Eskimo style Yup'ik clothing, intended to protect the wearer from cold weather, and are often made from traditional materials obtained through food gathering. Play dolls from the Yup'ik area were made of wood, bone, or walrus ivory and measured from one to twelve inches in height or more. Male and female dolls were often distinguished anatomically and can be told apart by the addition of ivory labrets for males and chin tattooing for females. The information about play dolls within Alaska Native cultures is sporadic. As is so often the case in early museum collections, it is difficult to distinguish dolls made for play from those made for ritual. There were always five dolls making up a family: a father, a mother, a son, a daughter, and a baby. Some human figurines were used by shamans.

An Eskimo yo-yo or Alaska yo-yo is a traditional two-balled skill toy played and performed by the Eskimo-speaking Alaska Natives, such as Inupiat, Siberian Yupik, and Yup'ik. It resembles fur-covered bolas and yo-yo. It is regarded as one of the most simple, yet most complex, cultural artifacts/toys in the world. The Eskimo yo-yo involves simultaneously swinging two sealskin balls suspended on caribou sinew strings in opposite directions with one hand. It is popular with Alaskans and tourists alike. This traditional toy is two unequal lengths of twine, joined together, with hand-made leather objects at the ends of the twine.

Susie Paallengetaq Silook is a carver, sculptor, writer and actress, of Siberian Yupik, Inupiaq and Irish descent. She was born in Gambell, Alaska.

Tom Akeya is an Inuit ivory carver. His work has been sold in multiple places.

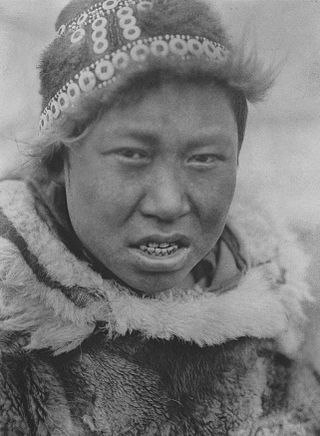

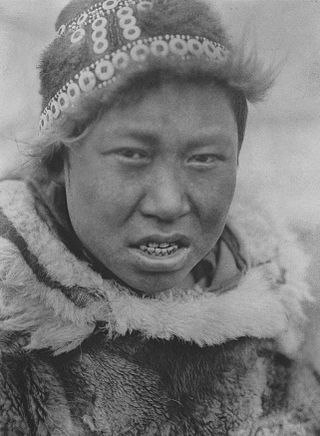

There is a long historical tradition of research on Inuit clothing across many fields. Since Europeans first made contact with the Inuit in the 16th century, documentation and research on Inuit clothing has included artistic depictions, academic writing, studies of effectiveness, and museum collections. Historically, European images of Inuit were sourced from the clothing worn by Inuit who travelled to Europe, clothing brought to museums by explorers, and from written accounts of travels to the Arctic.