Tiberias is an Israeli city on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. A major Jewish center during Late Antiquity, it has been considered since the 16th century one of Judaism's Four Holy Cities, along with Jerusalem, Hebron, and Safed. In 2022, it had a population of 48,472.

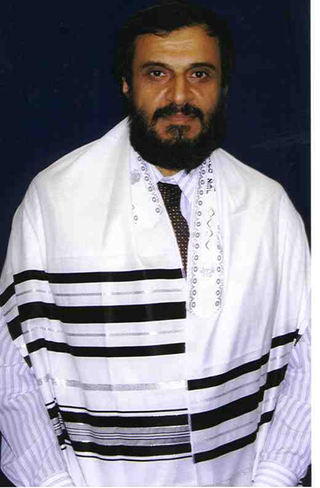

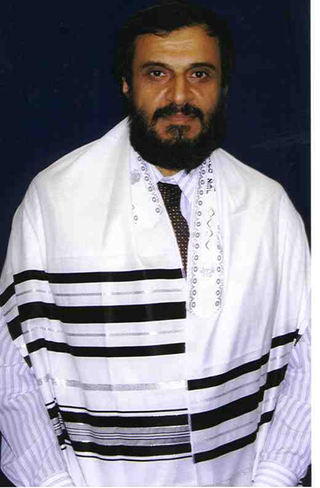

A tallit is a fringed garment worn as a prayer shawl by religious Jews. The tallit has special twined and knotted fringes known as tzitzit attached to its four corners. The cloth part is known as the beged ("garment") and is usually made from wool or cotton, although silk is sometimes used for a tallit gadol.

Safed is a city in the Northern District of Israel. Located at an elevation of up to 937 m (3,074 ft), Safed is the highest city in the Galilee and in Israel.

Jacob Berab, also spelled Berav or Bei-Rav, known as Mahari Beirav, was an influential rabbi and talmudist best known for his attempt to reintroduce classical semikhah (ordination).

Eliyahu de Vidas was a 16th-century rabbi in Ottoman Palestine. He was primarily a disciple of Rabbis Moses ben Jacob Cordovero and also Isaac Luria. De Vidas is known for his expertise in the Kabbalah. He wrote Reshit Chochmah, or "The Beginning of Wisdom," a pietistic work that is still widely studied by Orthodox Jews today. Just as his teacher Rabbi Moses Cordovero created an ethical work according to kabbalistic principles in his Tomer Devorah, Rabbi de Vidas created an even more expansive work on the spiritual life with his Reishit Chochmah. This magnum opus is largely based on the Zohar, but also reflects a wide range of traditional sources. The author lived in Safed and Hebron, and was one of a group of prominent kabbalists living in Hebron during the late 16th and early 17th-century.

Menahem ben Moshe Bavli, also known as Menahem Ben Moshe ha-Bavli, was a Jewish rabbi and author of the 1571 book Ta'amei Ha-Misvot.

Moses ben Joseph di Trani the Elder, known by his acronym Mabit was a 16th-century rabbi in Safed.

Abulafia or Abolafia is a Sephardi Jewish surname whose etymological origin is in the Arabic language. The family name, like many other Hispanic-origin Sephardic Jewish surnames, originated in Spain among Spanish Jews (Sephardim), during the time when it was ruled as Al-Andalus by Arabic-speaking Moors.

Peki'in or Buqei'a, is a Druze–Arab town with local council status in Israel's Northern District. It is located eight kilometres east of Ma'alot-Tarshiha in the Upper Galilee. In 2022 it had a population of 6,104. The majority of residents are Druze (78%), with a large Christian (20.8%) and Muslim (1.2%) minorities.

The history of the Jews and Judaism in the Land of Israel begins in the 2nd millennium BCE, when Israelites emerged as an outgrowth of southern Canaanites. During biblical times, a postulated United Kingdom of Israel existed but then split into two Israelite kingdoms occupying the highland zone: the Kingdom of Israel (Samaria) in the north, and the Kingdom of Judah in the south. The Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire, and the Kingdom of Judah by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Initially exiled to Babylon, upon the defeat of the Neo-Babylonian Empire by the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great, many of the Jewish exiles returned to Jerusalem, building the Second Temple.

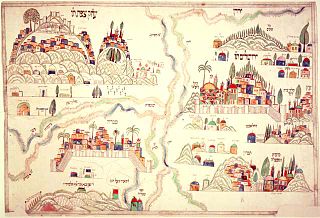

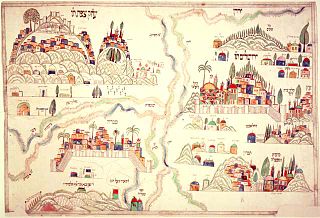

The Four Holy Cities of Judaism are the cities of Jerusalem, Hebron, Safed and Tiberias, which were the four main centers of Jewish life after the Ottoman conquest of Palestine.

Ashkenazi is a surname of Jewish origin. The term Ashkenaz refers to the area along the Rhine in Western Europe where diaspora Jews settled and formed communities during the Middle Ages.

The Old Yishuv were the Jewish communities of the region of Palestine during the Ottoman period, up to the onset of Zionist aliyah waves, and the consolidation of the new Yishuv by the end of World War I. Unlike the new Yishuv, characterized by secular and Zionist ideologies promoting labor and self-sufficiency, the Old Yishuv primarily consisted of religious Jews who relied on external donations (halukka) for support.

Kfar Hananya is a community settlement in the Galilee in northern Israel under the administration of the Merom HaGalil Regional Council. In 2022 it had a population of 781.The village marks the border between the historic Upper and Lower Galilee regions. Lower Galilee is defined in the Mishnah as the area south of Kfar Hananya where the Sycamore Fig tree grows.

The 1834 looting of Safed was a month-long attack on the Jewish community of Safed in the Sidon Eyalet of the Ottoman Empire during the Peasants' revolt in Palestine. It began on Sunday, June 15, the day after the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, and lasted for 33 days. It has been described as a spontaneous attack on a defenseless population during the armed uprising against the rule of Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt, the Ottoman governor. The event took place during a power vacuum while Ibrahim Pasha was fighting to quell the wider revolt in Jerusalem.

By the time the Ottoman Empire rose to power in the 14th and 15th centuries, there had been Jewish communities established throughout the region. The Ottoman Empire lasted from the early 12th century until the end of World War I and covered parts of Southeastern Europe, Anatolia, and much of the Middle East. The experience of Jews in the Ottoman Empire is particularly significant because the region "provided a principal place of refuge for Jews driven out of Western Europe by massacres and persecution."

The history of Palestinian rabbis encompasses the Israelites from the Anshi Knesses HaGedola period up until modern times, but most significantly refers to the early Jewish sages who dwelled in the Holy Land and compiled the Mishna and its later commentary, the Jerusalem Talmud. During the Talmudic and later Geonim period, Palestinian rabbis exerted influence over Syria and Egypt, whilst the authorities in Babylonia had held sway over the Jews of Iraq and Iran. While the Jerusalem Talmud was not to become authoritative against the Babylonian Talmud, the liturgy developed by Palestinian rabbis was later destined to form the foundation of the minhag Ashkenaz that was used by nearly all Ashkenazi communities across Europe before Hasidic Judaism.

The Safed attacks were an incident that took place in Safed soon after the Turkish Ottomans had ousted the Mamluks and taken Levant during the Ottoman–Mamluk War in 1517. At the time the town had roughly 300 Jewish households. The severe blow took place as Mamluks clashed bloodily with the new Ottoman authorities. The view that the riot's impact on the Jews of Safed was severe is contested.

Sefunot was a Hebrew-language academic journal, published annually, dealing with the study of Jewish communities in the East, from the end of the Middle Ages unto the present time. It was initiated by Meir Benayahu, and jointly published by the Ben Zvi Institute and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. A total of 26 books have been published in 25 volumes. The first book was published in 1956 and the last in 2017. The appellative Sefunot was chosen for the Annual, as it has the distinct meaning of "those things concealed," an allusion to the obscure nature of these Jewish communities.