Related Research Articles

The Indian National Army was a collaborationist armed unit of Indian collaborators that fought under the command of the Japanese Empire. It was founded on 1 September 1942 in Southeast Asia during World War II.

The Indian Army during World War II, a British force also referred to as the British Indian Army, began the war, in 1939, numbering just under 200,000 men. By the end of the war, it had become the largest volunteer army in history, rising to over 2.5 million men in August 1945. Serving in divisions of infantry, armour and a fledgling airborne force, they fought on three continents in Africa, Europe and Asia.

During the Second World War (1939–1945), India was a part of the British Empire. British India officially declared war on Nazi Germany in September 1939. India, as a part of the Allied Nations, sent over two and a half million soldiers to fight under British command against the Axis powers. India was also used as the base for American operations in support of China in the China Burma India Theater.

The Indian Army during British rule, also referred to as the British Indian Army, was the main military force of the British Indian Empire until 1947. It was responsible for the defence of both British India and the princely states, which could also have their own armies. As quoted in the Imperial Gazetteer of India, "The British Government has undertaken to protect the dominions of the Native princes from invasion and even from rebellion within: its army is organized for the defence not merely of British India, but of all possessions under the suzerainty of the King-Emperor." The Indian Army was an important part of the forces of the British Empire, in India and abroad, particularly during the First World War and the Second World War.

The Battle of Imphal took place in the region around the city of Imphal, the capital of the state of Manipur in Northeast India from March until July 1944. Japanese armies attempted to destroy the Allied forces at Imphal and invade India, but were driven back into Burma with heavy losses. Together with the simultaneous Battle of Kohima on the road by which the encircled Allied forces at Imphal were relieved, the battle was the turning point of the Burma campaign, part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II. The Japanese defeat at Kohima and Imphal was the largest up until that time, with many of the Japanese deaths resulting from starvation, disease and exhaustion suffered during their retreat. According to a voting in a contest run by the British National Army Museum, the Battle of Imphal was bestowed as Britain's Greatest Battle in 2013.

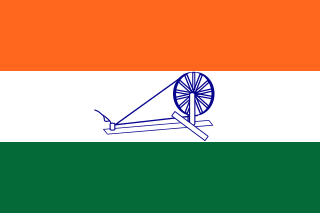

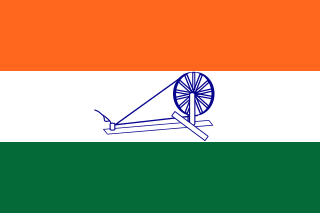

The Provisional Government of Free India or, more simply, Azad Hind, was a short-lived Japanese-supported provisional government in India. It was established in Japanese occupied Singapore during World War II in October 1943 and has been considered a puppet state of the Empire of Japan.

The Battle of the Admin Box took place on the southern front of the Burma campaign from 5 to 23 February 1944, in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II.

The concurrent Battle of Meiktila and Battle of Mandalay were decisive engagements near the end of the Burma campaign during World War II. Collectively, they are sometimes referred to as the Battle of Central Burma. Despite logistical difficulties, the Allies were able to deploy large armoured and mechanised forces in Central Burma, and also possessed air supremacy. Most of the Japanese forces in Burma were destroyed during the battles, allowing the Allies to later recapture the capital, Rangoon, and reoccupy most of the country with little organised opposition.

Mohan Singh was a British Indian Army officer, and later member of the Indian Independence Movement, best known for founding and leading the Indian National Army in South East Asia during World War II. The unit was formed by Singh. Following Indian independence, Mohan Singh later served in public life as a Member of Parliament in the Rajya Sabha of the Indian Parliament. He was a member of the Indian National Army (INA).

The Indian National Army trials was the British Indian trial by court-martial of a number of officers of the Indian National Army (INA) between November 1945 and May 1946, on various charges of treason, torture, murder and abetment to murder, during the Second World War.

The Bidadari Resolutions were set of resolutions adopted by the nascent Indian National Army in April 1942 that declared the formation of the INA and its aim to launch an armed struggle for Indian independence. The resolution was declared at a prisoner-of-war camp at the Bidadari in Singapore during Japanese occupation of the island.

The Rani of Jhansi Regiment was the women's regiment of the Indian National Army, the armed force formed by Indian nationalists in 1942 in Southeast Asia with the aim of overthrowing the British Raj in colonial India, with Japanese assistance. It was one of the all-female combat regiments of the Second World War on all sides. Led by Captain Lakshmi Swaminathan, the unit was raised in July 1943 with volunteers from the expatriate Indian population in Southeast Asia. The unit was named the "Rani Jhansi Regiment" after Rani Lakshmi Bai, Rani of Jhansi, a renowned Indian queen and freedom fighter.

The First Indian National Army was the Indian National Army as it existed between February and December 1942. It was formed with Japanese aid and support after the Fall of Singapore and consisted of approximately 12,000 of the 40,000 Indian prisoners of war who were captured either during the Malayan campaign or surrendered at Singapore. It was formally proclaimed in April 1942 and declared the subordinate military wing of the Indian Independence League in June that year. The unit was formed by Mohan Singh. The unit was dissolved in December 1942 after apprehensions of Japanese motives with regards to the INA led to disagreements and distrust between Mohan Singh and INA leadership on one hand, and the League's leadership, most notably Rash Behari Bose. Later on, the leadership of the Indian National Army was handed to Subhas Chandra Bose. A large number of the INAs initial volunteers, however, later went on to join the INA in its second incarnation under Subhas Chandra Bose.

The Farrer Park address was an assembly of the surrendered Indian troops of the British Indian Army held at Farrer Park in Singapore on 17 February 1942, two days after the Fall of Singapore. The assembly was marked by a series of three addresses in which the British Malaya Command formally surrendered the Indian troops of the British Indian Army to Major Fujiwara Iwaichi representing the Japanese military authority, followed by transfer of authority by Fujiwara to the command of Mohan Singh, and a subsequent address by Mohan Singh to the gathered troops declaring the formation of the Indian National Army to fight the Raj, asking for volunteers to join the army.

The Battles and Operations involving the Indian National Army during World War II were all fought in the South-East Asian theatre. These range from the earliest deployments of the INA's preceding units in espionage during Malayan Campaign in 1942, through the more substantial commitments during the Japanese Ha Go and U Go offensives in the Upper Burma and Manipur region, to the defensive battles during the Allied Burma campaign. The INA's brother unit in Europe, the Indische Legion did not see any substantial deployment although some were engaged in Atlantic wall duties, special operations in Persia and Afghanistan, and later a small deployment in Italy. The INA was not considered a significant military threat. However, it was deemed a significant strategic threat especially to the Indian Army, with Wavell describing it as a target of prime importance.

The U Go offensive, or Operation C, was the Japanese offensive launched in March 1944 against forces of the British Empire in the northeast Indian regions of Manipur and the Naga Hills. Aimed at the Brahmaputra Valley, through the two towns of Imphal and Kohima, the offensive along with the overlapping Ha Go offensive was one of the last major Japanese offensives during the Second World War. The offensive culminated in the Battles of Imphal and Kohima, where the Japanese and their allies were first held and then pushed back.

The Arakan Campaign of 1942–43 was the first tentative Allied attack into Burma, following the Japanese conquest of Burma earlier in 1942, during the Second World War. The British Army and British Indian Army were not ready for offensive actions in the difficult terrain they encountered, nor had the civil government, industry and transport infrastructure of Eastern India been organised to support the Army on the frontier with Burma. Japanese defenders occupying well-prepared positions repeatedly repulsed the British and Indian forces, who were then forced to retreat when the Japanese received reinforcements and counter-attacked.

The 5th Light Infantry was an infantry regiment of the Bengal Army and later of the raj-period British Indian Army. It could trace its lineage back to 1803, when it was raised as the 2nd Battalion, 21st Bengal Native Infantry. The regiment was known by a number of different names: the 42nd Bengal Native Infantry 1824–1842, the 42nd Bengal Native (Light) Infantry 1842–1861, the 5th Bengal Native (Light) Infantry 1861–1885 and the 5th Bengal (Light) Infantry 1885–1903. Its final designation 5th Light Infantry was a result of the Kitchener Reforms of the Indian Army, when all the old presidency titles (Bengal) were removed. During World War I the regiment was stationed in Singapore and was notorious for its involvement in the 1915 Singapore Mutiny. The regiment was disbanded in 1922, after another set of reforms of the post World War I Indian Army.

The Combined Services Detailed Interrogation Centre (India), or CSDIC (I) for short, was the Indian branch of the CSDIC, established during World War II. Established along with the parent section at the start of hostilities in Europe, the branch developed as an important tool for interrogation of enemy troops and informant from November 1942, when the first information emerged of the nascent Indian National Army. The organisation formed a part of the Jiffs campaign, and was initially tasked with identifying Indian troops at risk of defecting to the INA. By the end of the war its task had evolved into interrogating INA soldiers captured in Burma, Malaya and Europe, interrogating them regardless of rank and identifying soldiers as whitegrey or black on the basis of their commitment to Subhas Chandra Bose and Azad Hind. The classifications were to be important in rehabilitating INA soldiers into the British-Indian Army. Col. Hugh Toye, who worked with the unit, later went on to write the first substantive history on the INA in his book 1959 book The Springing Tiger.

The Indian National Army (INA) was a Japanese sponsored Indian military wing in Southeast Asia during the World War II, particularly active in Singapore, that was officially formed in April 1942 and disbanded in August 1945. It was formed with the help of the Japanese forces and was made up of roughly about 45 000 Indian prisoner of war (POWs) of British Indian Army, who were captured after the fall of Singapore on 15 February 1942. It was initially formed by Rash Behari Bose who headed it till April 1942 before handing the lead of INA over to Subhas Chandra Bose in 1943.

References

- Aldrich, Richard J. (2000), Intelligence and the War Against Japan: Britain, America and the Politics of Secret Service , Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-64186-1 .

- Bayly, Christopher; Harper, Tim (2005), Forgotten Armies: Britain's Asian Empire and the War with Japan, Penguin Books (UK) Ltd, ISBN 978-0-14-192719-0

- Fay, Peter W. (1993), The Forgotten Army: India's Armed Struggle for Independence, 1942–1945, Ann Arbor, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-08342-2 .

- Marston, Daniel (2014), The Indian Army and End of the Raj, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-89975-8 .

- Raj, James L. (1997) Making and unmaking of British India, Abacus.

- Singh, Gajendra. (2005), The Testimonies of Indian Soldiers and the Two World Wars: Between Self and Sepoy, Bloomsbury, ISBN 9781780938202 .

- Sundaram, Chandar (1995), "A Paper Tiger: the Indian National Army in Battle, 1944-1945", War & Society, 13 (1): 35–59, doi:10.1179/072924795791200187 .

- Toye, Hugh (1959), The Springing Tiger: A Study of the Indian National Army and of Netaji, Allied Publishers, ISBN 978-81-8424-392-5 .