Related Research Articles

Medieval music encompasses the sacred and secular music of Western Europe during the Middle Ages, from approximately the 6th to 15th centuries. It is the first and longest major era of Western classical music and followed by the Renaissance music; the two eras comprise what musicologists generally term as early music, preceding the common practice period. Following the traditional division of the Middle Ages, medieval music can be divided into Early (500–1150), High (1000–1300), and Late (1300–1400) medieval music.

In Western classical music, a motet is mainly a vocal musical composition, of highly diverse form and style, from high medieval music to the present. The motet was one of the pre-eminent polyphonic forms of Renaissance music. According to Margaret Bent, "a piece of music in several parts with words" is as precise a definition of the motet as will serve from the 13th to the late 16th century and beyond. The late 13th-century theorist Johannes de Grocheo believed that the motet was "not to be celebrated in the presence of common people, because they do not notice its subtlety, nor are they delighted in hearing it, but in the presence of the educated and of those who are seeking out subtleties in the arts".

Johannes Ciconia was an important Flemish composer and music theorist of trecento music during the late Medieval era. He was born in Liège, but worked most of his adult life in Italy, particularly in the service of the papal chapels in Rome and later and most importantly at Padua Cathedral.

Ars antiqua, also called ars veterum or ars vetus, is a term used by modern scholars to refer to the Medieval music of Europe during the High Middle Ages, between approximately 1170 and 1310. This covers the period of the Notre-Dame school of polyphony, and the subsequent years which saw the early development of the motet, a highly varied choral musical composition. Usually the term ars antiqua is restricted to sacred (church) or polyphonic music, excluding the secular (non-religious) monophonic songs of the troubadours, and trouvères. Although colloquially the term ars antiqua is used more loosely to mean all European music of the 13th century, and from slightly before.

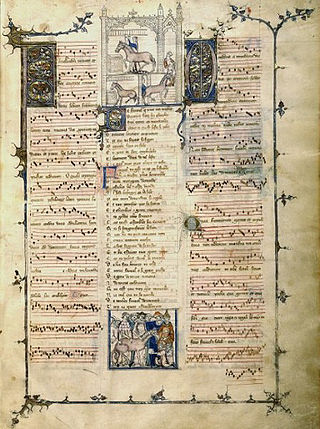

Ars nova refers to a musical style which flourished in the Kingdom of France and its surroundings during the Late Middle Ages. More particularly, it refers to the period between the preparation of the Roman de Fauvel (1310s) and the death of composer Guillaume de Machaut in 1377. The term is sometimes used more generally to refer to all European polyphonic music of the fourteenth century. For instance, the term "Italian ars nova" is sometimes used to denote the music of Francesco Landini and his compatriots, although Trecento music is the more common term for the contemporary 14th-century music in Italy. The "ars" in "ars nova" can be read as "technique", or "style". The term was first used in two musical treatises, titled Ars novae musicae by Johannes de Muris, and a collection of writings attributed to Philippe de Vitry often simply called "Ars nova" today. Musicologist Johannes Wolf first applied to the term as description of an entire era in 1904.

Franco of Cologne was a German music theorist and possibly a composer. He was one of the most influential theorists of the Late Middle Ages, and was the first to propose an idea which was to transform musical notation permanently: that the duration of any note should be determined by its appearance on the page, and not from context alone. The result was Franconian notation, described most famously in his Ars cantus mensurabilis.

Johannes de Garlandia was a French music theorist of the late ars antiqua period of medieval music. He is known for his work on the first treatise to explore the practice of musical notation of rhythm, De Mensurabili Musica.

Marchetto da Padova was an Italian music theorist and composer of the late medieval era. His innovations in notation of time-values were fundamental to the music of the Italian ars nova, as was his work on defining the modes and refining tuning. In addition, he was the first music theorist to discuss chromaticism.

Johannes de Muris, or John of Murs, was a French mathematician, astronomer, and music theorist best known for treatises on the ars nova musical style, titled Ars nove musice.

Johannes de Grocheio was a Parisian musical theorist of the early 14th century. His French name was Jean de Grouchy, but he is best known by his Latinized name. He was the author of the treatise Ars musicae, which describes the functions of sacred and secular music in and around Paris during his lifetime.

Johannes Alanus was an English composer. He wrote the motet Sub arturo plebs/Fons citharizancium/In omnem terram. Also attributed to him are the songs "Min frow, min frow" and "Min herze wil all zit frowen pflegen", both lieds, and "S'en vos por moy pitié ne truis", a virelai. O amicus/Precursoris, attributed simply to "Johannes", may be the work of the same composer.

Philippus de Caserta, was a medieval music theorist and composer associated with the style known as ars subtilior.

Sub Arturo plebs – Fons citharizantium – In omnem terram is an isorhythmic motet of the second part of the 14th century, written by an English composer known by the name of Johannes Alanus or John Aleyn. It stands in the tradition of the Ars nova, the fourteenth-century school of polyphonic music based in France. It is notable for the historical information it provides about contemporary music life in England, and for its spectacularly sophisticated use of complex rhythmic devices, which mark it as a prime example of the stylistic outgrowth of the Ars nova known today as Ars subtilior. It has been dated conjecturally to either around 1358, which, within that school of composition, would make its compositional technique exceptionally innovative for its own time, or some time later during the 1370s.

Early music of Britain and Ireland, from the earliest recorded times until the beginnings of the Baroque in the 17th century, was a diverse and rich culture, including sacred and secular music and ranging from the popular to the elite. Each of the major nations of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales retained unique forms of music and of instrumentation, but British music was highly influenced by continental developments, while British composers made an important contribution to many of the major movements in early music in Europe, including the polyphony of the Ars Nova and laid some of the foundations of later national and international classical music. Musicians from the British Isles also developed some distinctive forms of music, including Celtic chant, the Contenance Angloise, the rota, polyphonic votive antiphons, and the carol in the medieval era and English madrigals, lute ayres, and masques in the Renaissance era, which would lead to the development of English language opera at the height of the Baroque in the 18th century.

Prosdocimus de Beldemandis was an Italian mathematician, music theorist, and physician.

De Mensurabili Musica is a musical treatise from the early 13th century and is the first of two treatises traditionally attributed to French music theorist Johannes de Garlandia; the other is de plana musica. De Mensurabili Musica was the first to explain a modal rhythmic system that was already in use at the time: the rhythmic modes. The six rhythmic modes set out by the treatise are all in triple time and are made from combinations of the note values longa (long) and brevis (short) and are given the names trochee, iamb, dactyl, anapest, spondaic and tribrach, although trochee, dactyl and spondaic were much more common. It is evident how influential Garlandia's treatise has been by the number of theorists that have used its ideas. Much of the surviving music of the Notre Dame School from the 13th century is based on the rhythmic modes set out in De Mensurabili Musica.

Music in Medieval England, from the end of Roman rule in the fifth century until the Reformation in the sixteenth century, was a diverse and rich culture, including sacred and secular music and ranging from the popular to the elite.

The 1320s in music involved some events.

References

- Squire, William Barclay (1890). . In Stephen, Leslie; Lee, Sidney (eds.). Dictionary of National Biography . Vol. 24. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- Lefferts, Peter M. (2001). "Hanboys [Hauboys], John" . Grove Music Online . Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.12300. ISBN 978-1-56159-263-0.(subscription or UK public library membership required)