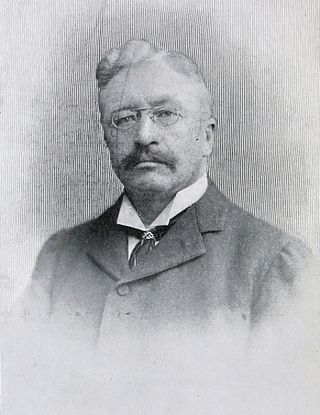

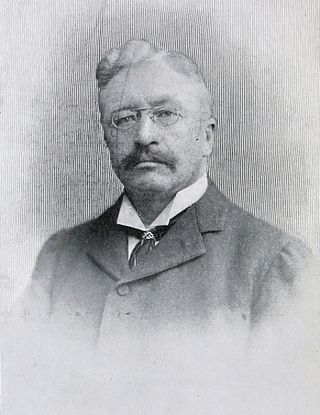

Charles Proteus Steinmetz was an American mathematician and electrical engineer and professor at Union College. He fostered the development of alternating current that made possible the expansion of the electric power industry in the United States, formulating mathematical theories for engineers. He made ground-breaking discoveries in the understanding of hysteresis that enabled engineers to design better electromagnetic apparatus equipment, especially electric motors for use in industry.

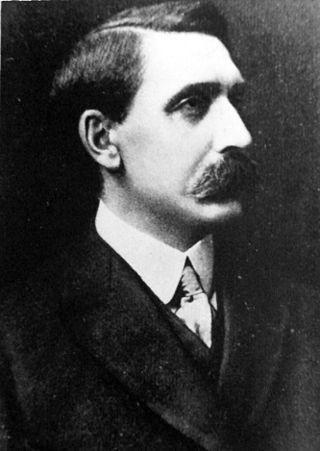

Sir John Ambrose Fleming was an English electrical engineer and physicist who invented the first thermionic valve or vacuum tube, designed the radio transmitter with which the first transatlantic radio transmission was made, and also established the right-hand rule used in physics.

The 1880s was a decade of the Gregorian calendar that began on January 1, 1880, and ended on December 31, 1889.

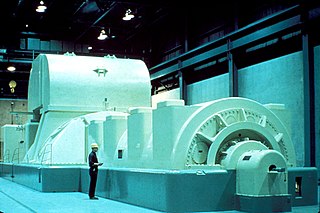

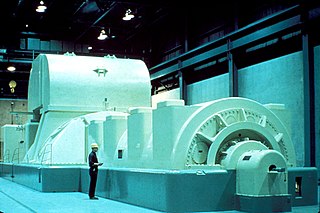

In electricity generation, a generator is a device that converts motion-based power or fuel-based power into electric power for use in an external circuit. Sources of mechanical energy include steam turbines, gas turbines, water turbines, internal combustion engines, wind turbines and even hand cranks. The first electromagnetic generator, the Faraday disk, was invented in 1831 by British scientist Michael Faraday. Generators provide nearly all the power for electrical grids.

Sir William Lawrence Bragg, known as Lawrence Bragg, was an Australian-born British physicist and X-ray crystallographer, discoverer (1912) of Bragg's law of X-ray diffraction, which is basic for the determination of crystal structure. He was joint recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1915, "For their services in the analysis of crystal structure by means of X-rays"; an important step in the development of X-ray crystallography.

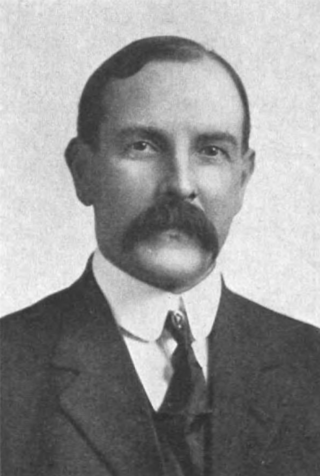

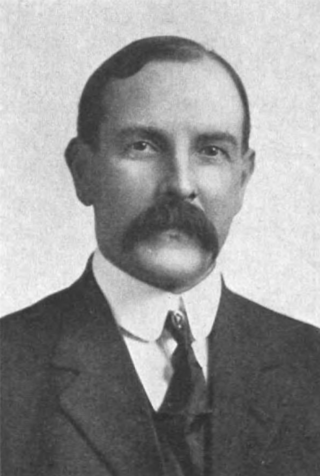

Elihu Thomson was an English-American engineer and inventor who was instrumental in the founding of major electrical companies in the United States, the United Kingdom and France.

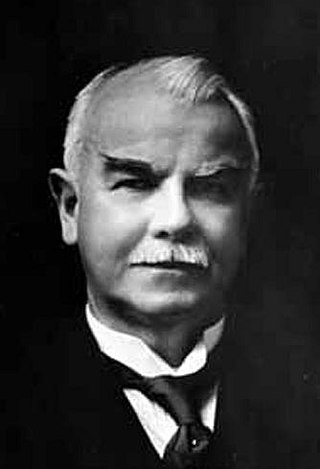

Arthur Edwin Kennelly was an American electrical engineer, physicist and mathematician.

Sir James Alfred EwingMInstitCE was a Scottish physicist and engineer, best known for his work on the magnetic properties of metals and, in particular, for his discovery of, and coinage of the word, hysteresis.

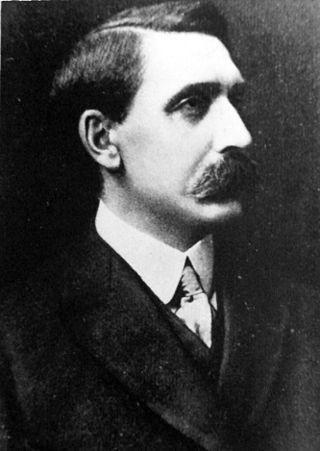

Sebastian Pietro Innocenzo Adhemar Ziani de Ferranti was a British electrical engineer and inventor who pioneered high-voltage AC power in the UK, patented the Ferranti dynamo and designed Deptford power station.

A homopolar generator is a DC electrical generator comprising an electrically conductive disc or cylinder rotating in a plane perpendicular to a uniform static magnetic field. A potential difference is created between the center of the disc and the rim with an electrical polarity that depends on the direction of rotation and the orientation of the field. It is also known as a unipolar generator, acyclic generator, disk dynamo, or Faraday disc. The voltage is typically low, on the order of a few volts in the case of small demonstration models, but large research generators can produce hundreds of volts, and some systems have multiple generators in series to produce an even larger voltage. They are unusual in that they can source tremendous electric current, some more than a million amperes, because the homopolar generator can be made to have very low internal resistance. Also, the homopolar generator is unique in that no other rotary electric machine can produce DC without using rectifiers or commutators.

This article details the history of electrical engineering.

The University of Cambridge's Department of Engineering is the largest department at the university. The main site is situated at Trumpington Street, to the south of the city centre of Cambridge. The department is currently headed by Professor Colm Durkan.

Bertram Hopkinson was a British patent lawyer and Professor of Mechanism and Applied Mechanics at Cambridge University. In this position he researched flames, explosions and metallurgy and became a pioneer designer of the internal combustion engine.

Alexander Siemens was a German electrical engineer.

Reinhold Rudenberg was a German-American electrical engineer and inventor, credited with many innovations in the electric power and related fields. Aside from improvements in electric power equipment, especially large alternating current generators, among others were the electrostatic-lens electron microscope, carrier-current communications on power lines, a form of phased array radar, an explanation of power blackouts, preferred number series, and the number prefix "Giga-".

Sir Charles Edward Inglis, was a British civil engineer. The son of a medical doctor, he was educated at Cheltenham College and won a scholarship to King's College, Cambridge, where he would later forge a career as an academic. Inglis spent a two-year period with the engineering firm run by John Wolfe-Barry before he returned to King's College as a lecturer. Working with Professors James Alfred Ewing and Bertram Hopkinson, he made several important studies into the effects of vibration on structures and defects on the strength of plate steel.

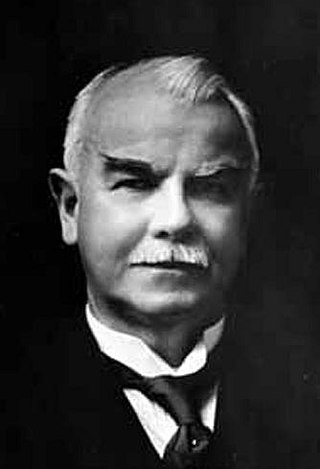

Edward Hopkinson was a British civil, mechanical and electrical engineer, and Conservative politician.

Henry Wilde was a wealthy individual from Manchester, England, who used his self-made fortune to indulge his interest in electrical engineering.

Baron Auguste de Méritens was a French electrical engineer of the 19th century.

James Edward Henry Gordon was a British electrical engineer, the son of James Alexander Gordon (1793–1872). He took his B.A. at Caius College, Cambridge in 1876.