The internal slave trade in the United States, also known as the domestic slave trade, the Second Middle Passage and the interregional slave trade, was the mercantile trade of enslaved people within the United States. It was most significant after 1808, when the importation of slaves from Africa was prohibited by federal law. Historians estimate that upwards of one million slaves were forcibly relocated from the Upper South, places like Maryland, Virginia, Kentucky, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Missouri, to the territories and then-new states of the Deep South, especially Georgia, Alabama, Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas.

John Lyons was a carpenter, bridge builder, cotton-plantation owner, and steamship captain of Louisiana, United States. Lyons is best known today as the enslaver of Peter of the scourged back, who escaped to Union lines in 1863, and whose whip-scarred body ultimately became a representative of the physical violence inherent to the American slavery system.

Shadrack Fluellen Slatter, usually listed as S. F. Slatter in advertisements and often called Col. Slatter in later life, was a 19th-century American slave trader and capitalist. In the 1830s and 1840s he was part of the coastwise slave trade in partnership with his older brother Hope H. Slatter, who bought slaves in Baltimore for S. F. Slatter to sell at New Orleans. It was typical for interstate traders like the Slatters to have a buying location in the Upper South and a selling location in the Lower South. After quitting the retail slave trade, he was a real estate developer and landlord in New Orleans. In the late 1850s he was heavily involved in promoting and funding the freelance invasion of Nicaragua by William Walker.

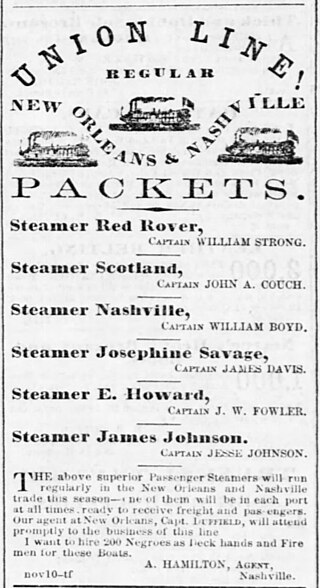

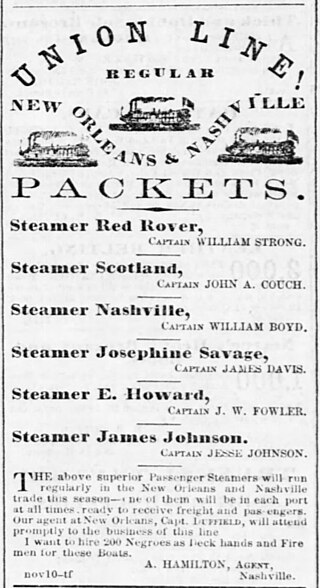

William L. Boyd Jr. was a slave trader, real estate broker, and steamboat captain of Nashville, Tennessee in the United States. In 1883 he was charged with murder in the shooting death of his girlfriend Birdie Patterson.

Capt. Montgomery Little, CSA was an American slave trader and a Confederate Army cavalry officer who served in Nathan Bedford Forrest's Escort Company. Little was killed in action during the American Civil War at the Battle of Thompson's Station.

Slave markets and slave jails in the United States were places used for the slave trade in the United States from the founding in 1776 until the total abolition of slavery in 1865. Slave pens, also known as slave jails, were used to temporarily hold enslaved people until they were sold, or to hold fugitive slaves, and sometimes even to "board" slaves while traveling. Slave markets were any place where sellers and buyers gathered to make deals. Some of these buildings had dedicated slave jails, others were negro marts to showcase the slaves offered for sale, and still others were general auction or market houses where a wide variety of business was conducted, of which "negro trading" was just one part.

Jordan Arterburn (1808–1875) and Tarlton Arterburn (1810–1883) were brothers and interstate slave traders of the 19th-century United States. They typically bought enslaved people in their home state of Kentucky in the upper south, and then moved them to Mississippi in the lower south, where there was a constant demand for enslaved laborers on the plantations of King Cotton. Their "negroes wanted" advertisements ran in Louisville newspapers almost continuously from 1843 to 1859. In 1876, Tarlton Arterburn claimed they had taken profits of "30 to 40 percent a head" during their slave-trading days, and that Northern abolitionist Harriet Beecher Stowe had visited the Arterburn slave pen in Louisville while researching Uncle Tom's Cabin and A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin. There is now a historical marker in Louisville at former site of the Arterburn slave jail, acknowledging the myriad abuses and human-rights violations that took place there.

Lewis C. Robards was a 19th-century American slave trader of Lexington, Kentucky. He had an unscrupulous reputation as a dealer, and he was widely known for his "special" offerings: fancy girls, meaning young, light-skinned enslaved women and girls offered for sexual exploitation. Robards was also considered a likely culprit in several cases of kidnapping into slavery. His slave pen was funded in part by a loan from John Hunt Morgan; when he could not repay the loan his premises were sold to Bolton, Dickens & Co., a multi-state slave-trading firm based in West Tennessee.

Theophilus Freeman was a 19th-century American slave trader of Virginia, Louisiana and Mississippi. He was known in his own time as wealthy and problematic. Freeman's business practices were described in two antebellum American slave narratives—that of John Brown and that of Solomon Northup—and he appears as a character in both filmed dramatizations of Northrup's Twelve Years a Slave.

Thomas McCargo, also styled Thos. M'Cargo, was a 19th-century American slave trader who worked in Virginia, Kentucky, Mississippi and Louisiana. He is best remembered today for being one of the slave traders aboard the Creole, which was a coastwise slave ship that was commandeered by the enslaved men aboard and sailed to freedom in the British Caribbean. The takeover of the Creole is considered the most successful slave revolt in antebellum American history.

Bernard Kendig was an American slave trader, primarily operating in New Orleans. He sold enslaved people at comparatively low prices, and dealt primarily in and around Louisiana, rather than importing large numbers of enslaved people from the border states or Chesapeake region. Kendig was sued a number of times under Louisiana's redhibition (warranty) laws and accused of having willfully misrepresented the health or character of slaves he sold.

Pierre Michel La Pice de Bergondy, generally known as P. M. Lapice, sometimes Peter Lapice, was a merchant, sugar planter, and large-scale enslaver of 19th-century Mississippi and Louisiana in the United States. He was credited with Louisiana sugar-industry firsts, including producing the first white sugar, erecting the first cane-mill with five rollers, and building the first successful bagasse burner.

Jonathan Means Wilson, usually advertising as J. M. Wilson, was a 19th-century slave trader of the United States who trafficked people from the Upper South to the Lower South as part of the interstate slave trade. Originally a trading agent and associate to Baltimore traders, he later operated a slave depot in New Orleans. At the time of the 1860 U.S. census of New Orleans, Wilson had the second-highest net worth of the 34 residents who listed their occupation as "slave trader".

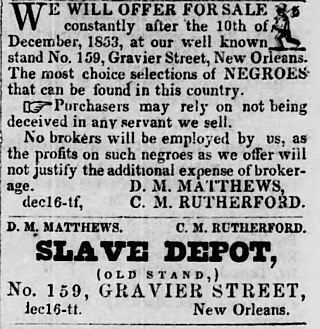

Poindexter & Little was a 19th-century American slave-trading company with operations in Tennessee and Louisiana. The principals were likely Thomas B. Poindexter, John J. Poindexter, Montgomery Little, William Little, Chauncey Little, and Benjamin Little. The Littles were brothers; the Poindexters were most likely brothers but possibly cousins. At the time of the 1860 census, Thomas B. Poindexter had the highest declared net worth of any person who listed their occupation as a slave trader in New Orleans. In 1861 they had a slave depot located at 48 Baronne in New Orleans.

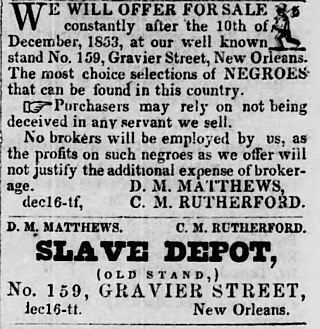

Thomas B. Poindexter was an American slave trader and cotton planter. He had the highest net worth, US$350,000, of the 34 active resident slave traders indexed as such in the 1860 New Orleans census, ahead of Jonathan M. Wilson and Bernard Kendig.

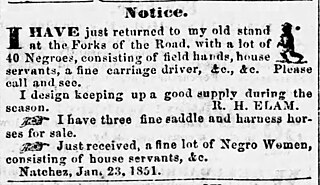

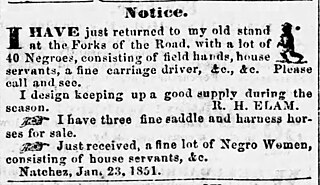

Robert H. Elam, usually advertising as R. H. Elam, was an American interstate slave trader who worked in Tennessee, Kentucky, Louisiana, and Mississippi.

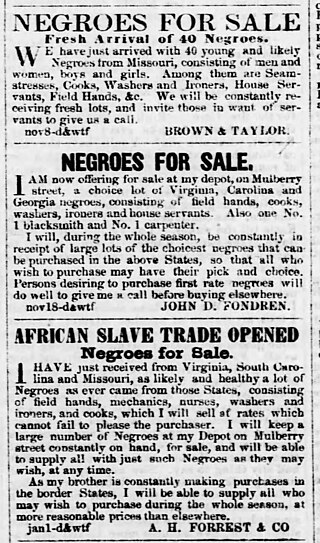

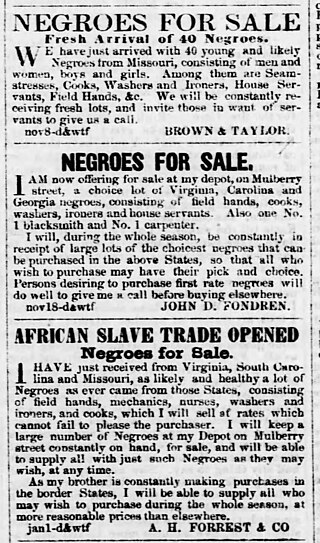

Aaron H. Forrest was one of the six Forrest brothers who engaged in the interregional slave trade in the United States prior to the American Civil War. He may have also owned or managed cotton plantations in Mississippi. He led a Confederate cavalry unit composed of volunteers from the Yazoo River region of Mississippi during the American Civil War. He died in 1864, apparently from illness.

John Rucker White was a plantation owner, farmer, and interstate slave trader working out of the U.S. state of Missouri in the 25 years prior to the American Civil War.

Calvin Morgan Rutherford, generally known as C. M. Rutherford, was a 19th-century American interstate slave trader. Rutherford had a wide geographic reach, trading nationwide from the Old Dominion of Virginia to as far west as Texas. Rutherford had ties to former Franklin & Armfield associates, worked in Kentucky for several years, advertised to markets throughout Louisiana and Mississippi, and was a major figure in the New Orleans slave trade for at least 20 years. Rutherford also invested his money in steamboats and hotels.