Mosses are small, non-vascular flowerless plants in the taxonomic division Bryophytasensu stricto. Bryophyta may also refer to the parent group bryophytes, which comprise liverworts, mosses, and hornworts. Mosses typically form dense green clumps or mats, often in damp or shady locations. The individual plants are usually composed of simple leaves that are generally only one cell thick, attached to a stem that may be branched or unbranched and has only a limited role in conducting water and nutrients. Although some species have conducting tissues, these are generally poorly developed and structurally different from similar tissue found in vascular plants. Mosses do not have seeds and after fertilisation develop sporophytes with unbranched stalks topped with single capsules containing spores. They are typically 0.2–10 cm (0.1–3.9 in) tall, though some species are much larger. Dawsonia, the tallest moss in the world, can grow to 50 cm (20 in) in height. There are approximately 12,000 species.

Sphagnum is a genus of approximately 380 accepted species of mosses, commonly known as sphagnum moss, also bog moss and quacker moss. Accumulations of Sphagnum can store water, since both living and dead plants can hold large quantities of water inside their cells; plants may hold 16 to 26 times as much water as their dry weight, depending on the species. The empty cells help retain water in drier conditions.

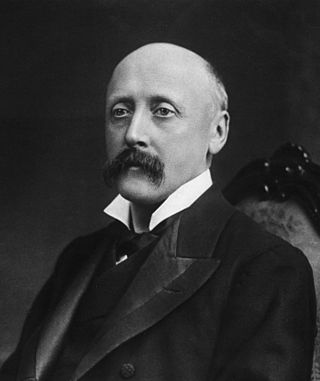

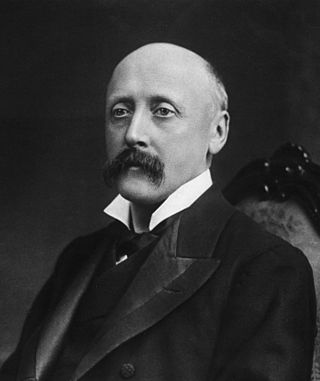

Joseph Charles Arthur was a pioneer American plant pathologist and mycologist best known for his work with the parasitic rust fungi (Pucciniales). He was a charter member of the Botanical Society of America, the Mycological Society of America, and the American Phytopathological Society. He was an elected member of both the American Philosophical Society and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He was a recipient of the first Doctorate in Sciences awarded by Cornell University. The standard author abbreviation Arthur is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Elmer Drew Merrill was an American botanist and taxonomist. He spent more than twenty years in the Philippines where he became a recognized authority on the flora of the Asia-Pacific region. Through the course of his career he authored nearly 500 publications, described approximately 3,000 new plant species, and amassed over one million herbarium specimens. In addition to his scientific work he was an accomplished administrator, college dean, university professor and editor of scientific journals.

Sir Isaac Bayley Balfour, KBE, FRS, FRSE was a Scottish botanist. He was Regius Professor of Botany at the University of Glasgow from 1879 to 1885, Sherardian Professor of Botany at the University of Oxford from 1884 to 1888, and Professor of Botany at the University of Edinburgh from 1888 to 1922.

The Harvard University Herbaria and Botanical Museum are institutions located on the grounds of Harvard University at 22 Divinity Avenue, Cambridge, Massachusetts. The Botanical Museum is one of three which comprise the Harvard Museum of Natural History.

Oakes Ames was an American biologist specializing in orchids. His estate is now the Borderland State Park in Massachusetts. He was the son of Governor of Massachusetts Oliver Ames and grandson of Congressman Oakes Ames.

William Trelease was an American botanist, entomologist, explorer, writer and educator. This botanist is denoted by the author abbreviation Trel. when citing a botanical name.

George Neville Jones, usually known as G. Neville Jones, (1903–1970) was an English-born botanist who spent most of his life and career in the United States. He was a professor of botany at the University of Illinois (Urbana) at the time of his death.

Daniel Elliot Stuntz was an American mycologist. He was often called "Bud" by his family and colleagues. When Stuntz was young, his immediate and extended family moved from Ohio to Seattle. He had a sister named Alice Stuntz Marionneaux, whom he frequently visited in the later years. Stuntz's father, Chauncey Richards Stuntz, who worked in the sugarcane business, would be absent to work for most of the time. In 1920s, he was promoted as the general manager of a sugar mill, 'Jobabo' in Oriente Province in Cuba. During his father's absence, Stuntz' mother, Evelyn Elliot Stuntz, managed the family and arranged the children's summer vacations.

Jesse More Greenman was an American botanist. He specialized in tropical flora, with emphasis on plants from Mexico and Central America. He was an authority on the genus Senecio and noted for his work at the Missouri Botanical Garden.

Charles Walker Cathcart, was a Scottish surgeon who worked for most of his career at the Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh (RIE). As a young man he had represented Scotland at rugby on three occasions. During the First World War he jointly published an account of the value of sphagnum moss as a wound dressing which led to its widespread use by the British Army for that purpose.

Lois Clark (1884–1967) was an American botanist, bryologist, and professor who studied plants of the Northwestern United States, particularly the genus Frullania. She taught at the University of Idaho and the University of Washington. The standard author abbreviation L.Clark is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Howard Alvin Crum was an American botanist dedicated to the study of mosses, and was a renowned expert on the North American bryoflora.

Perry Daniel Strausbaugh was an American botanist and expert in the flora of West Virginia. The standard author abbreviation Strausb. is used to indicate this person as the author when citing a botanical name.

Louis Hermann Pammel (1862–1931) was an American botanist, conservationist, and professor of botany.

Harry James Smith was an American playwright and novelist. His best known plays include A Tailor-Made Man, first produced in 1917 and adapted into films of the same name in 1922 and 1931. His 1913 play Blackbirds was also adapted into films. Educated at Williams College and Harvard University, he also studied biology, taught briefly at Oberlin University and was an editor at The Atlantic Monthly before turning to writing full-time. He was killed in a traffic collision in British Columbia while collecting peat moss for its use in surgical dressings.

George Burton Rigg was an American botanist and ecologist, specializing in sphagnum bogs. In 1956 he received the Eminent Ecologist Award from the Ecological Society of America.

Theodore Christian Frye was an American botany professor and one of the world's leading experts on bryology.

Albert LeRoy Andrews (1878–1961) was a professor of Germanic philology and an avocational bryologist, known as "one of the world’s foremost bryologists and the American authority on Sphagnaceae." From 1922 to 1923 he was the president of the Sullivant Moss Society, renamed in 1970 the American Bryological and Lichenological Society.