Related Research Articles

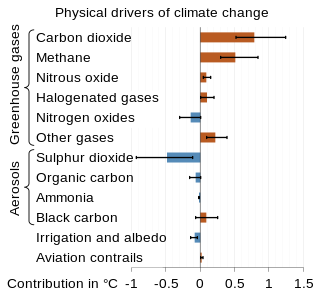

The scientific community has been investigating the causes of climate change for decades. After thousands of studies, it came to a consensus, where it is "unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land since pre-industrial times." This consensus is supported by around 200 scientific organizations worldwide, The dominant role in this climate change has been played by the direct emissions of carbon dioxide from the burning of fossil fuels. Indirect CO2 emissions from land use change, and the emissions of methane, nitrous oxide and other greenhouse gases play major supporting roles.

The Arctic is a polar region located at the northernmost part of Earth. The Arctic region, from the IERS Reference Meridian travelling east, consists of parts of northern Norway, northernmost Sweden, northern Finland, Russia, the United States (Alaska), Canada, Danish Realm (Greenland), and northern Iceland, along with the Arctic Ocean and adjacent seas. Land within the Arctic region has seasonally varying snow and ice cover, with predominantly treeless permafrost under the tundra. Arctic seas contain seasonal sea ice in many places.

Climate variability includes all the variations in the climate that last longer than individual weather events, whereas the term climate change only refers to those variations that persist for a longer period of time, typically decades or more. Climate change may refer to any time in Earth's history, but the term is now commonly used to describe contemporary climate change, often popularly referred to as global warming. Since the Industrial Revolution, the climate has increasingly been affected by human activities.

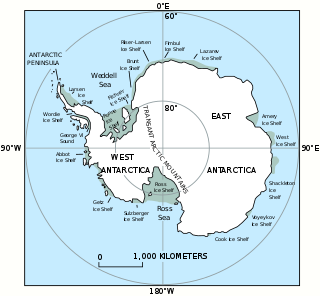

The climate of Antarctica is the coldest on Earth. The continent is also extremely dry, averaging 166 mm (6.5 in) of precipitation per year. Snow rarely melts on most parts of the continent, and, after being compressed, becomes the glacier ice that makes up the ice sheet. Weather fronts rarely penetrate far into the continent, because of the katabatic winds. Most of Antarctica has an ice-cap climate with extremely cold and dry weather.

The West Antarctic Ice Sheet (WAIS) is the segment of the continental ice sheet that covers West Antarctica, the portion of Antarctica on the side of the Transantarctic Mountains that lies in the Western Hemisphere. It is classified as a marine-based ice sheet, meaning that its bed lies well below sea level and its edges flow into floating ice shelves. The WAIS is bounded by the Ross Ice Shelf, the Ronne Ice Shelf, and outlet glaciers that drain into the Amundsen Sea.

Climate engineering is an umbrella term for both carbon dioxide removal and solar radiation modification, when applied at a planetary scale. However, these two processes have very different characteristics. For this reason, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change no longer uses this overarching term. Carbon dioxide removal approaches are part of climate change mitigation. Solar radiation modification is reflecting some sunlight back to space. Some publications place passive radiative cooling into the climate engineering category. This technology increases the Earth's thermal emittance. The media tends to use climate engineering also for other technologies such as glacier stabilization, ocean liming, and iron fertilization of oceans. The latter would modify carbon sequestration processes that take place in oceans.

The Antarctic ice sheet is a continental glacier covering 98% of the Antarctic continent, with an area of 14 million square kilometres and an average thickness of over 2 kilometres (1.2 mi). It is the largest of Earth's two current ice sheets, containing 26.5 million cubic kilometres of ice, which is equivalent to 61% of all fresh water on Earth. Its surface is nearly continuous, and the only ice-free areas on the continent are the dry valleys, nunataks of the Antarctic mountain ranges, and sparse coastal bedrock. However, it is often subdivided into East Antarctic ice sheet (EAIS), West Antarctic ice sheet (WAIS), and Antarctic Peninsula (AP), due to the large differences in topography, ice flow, and glacier mass balance between the three regions.

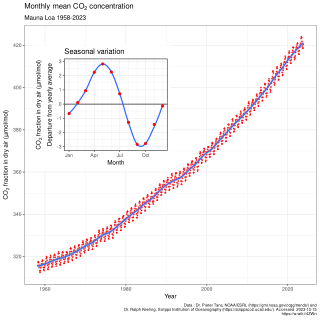

In Earth's atmosphere, carbon dioxide is a trace gas that plays an integral part in the greenhouse effect, carbon cycle, photosynthesis and oceanic carbon cycle. It is one of several greenhouse gases in the atmosphere of Earth. The current global average concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is 421 ppm (0.04%) as of May 2022. This is an increase of 50% since the start of the Industrial Revolution, up from 280 ppm during the 10,000 years prior to the mid-18th century. The increase is due to human activity.

Ocean heat content (OHC) or ocean heat uptake (OHU) is the energy absorbed and stored by oceans. To calculate the ocean heat content, it is necessary to measure ocean temperature at many different locations and depths. Integrating the areal density of a change in enthalpic energy over an ocean basin or entire ocean gives the total ocean heat uptake. Between 1971 and 2018, the rise in ocean heat content accounted for over 90% of Earth's excess energy from global heating. The main driver of this increase was anthropogenic forcing via rising greenhouse gas emissions. By 2020, about one third of the added energy had propagated to depths below 700 meters.

Due to climate change in the Arctic, this polar region is expected to become "profoundly different" by 2050. The speed of change is "among the highest in the world", with the rate of warming being 3-4 times faster than the global average. This warming has already resulted in the profound Arctic sea ice decline, the accelerating melting of the Greenland ice sheet and the thawing of the permafrost landscape. These ongoing transformations are expected to be irreversible for centuries or even millennia.

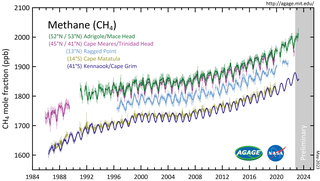

In climate science, a tipping point is a critical threshold that, when crossed, leads to large, accelerating and often irreversible changes in the climate system. If tipping points are crossed, they are likely to have severe impacts on human society and may accelerate global warming. Tipping behavior is found across the climate system, for example in ice sheets, mountain glaciers, circulation patterns in the ocean, in ecosystems, and the atmosphere. Examples of tipping points include thawing permafrost, which will release methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, or melting ice sheets and glaciers reducing Earth's albedo, which would warm the planet faster. Thawing permafrost is a threat multiplier because it holds roughly twice as much carbon as the amount currently circulating in the atmosphere.

This is a list of climate change topics.

Arctic methane release is the release of methane from Arctic ocean floors, lake bottoms, wetlands and soils in permafrost regions of the Arctic. While it is a long-term natural process, methane release is exacerbated by global warming. This results in a positive climate change feedback, as methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. The Arctic region is one of many natural sources of methane. Climate change could accelerate methane release in the Arctic, due to the release of methane from existing stores, and from methanogenesis in rotting biomass. When permafrost thaws as a consequence of warming, large amounts of organic material can become available for methanogenesis and may ultimately be released as methane.

Solar radiation modification (SRM), or solar geoengineering, refers to a range of approaches to limit global warming by increasing the amount of sunlight that the atmosphere reflects back to space or by reducing the trapping of outgoing thermal radiation. Among the multiple potential approaches, stratospheric aerosol injection is the most-studied, followed by marine cloud brightening. SRM could be a temporary measure to limit climate-change impacts while greenhouse gas emissions are reduced and carbon dioxide is removed, but would not be a substitute for reducing emissions.

Arctic geoengineering is a type of climate engineering in which polar climate systems are intentionally manipulated to reduce the undesired impacts of climate change. As a proposed solution to climate change, arctic geoengineering is relatively new and has not been implemented on a large scale. It is based on the principle that Arctic albedo plays a significant role in regulating the Earth's temperature and that there are large-scale engineering solutions that can help maintain Earth's hemispheric albedo. According to researchers, projections of sea ice loss, when adjusted to account for recent rapid Arctic shrinkage, indicate that the Arctic will likely be free of summer sea ice sometime between 2059 and 2078. Advocates for Arctic geoengineering believe that climate engineering methods can be used to prevent this from happening.

Stratospheric aerosol injection is a proposed method of solar geoengineering to reduce global warming. This would introduce aerosols into the stratosphere to create a cooling effect via global dimming and increased albedo, which occurs naturally from volcanic winter. It appears that stratospheric aerosol injection, at a moderate intensity, could counter most changes to temperature and precipitation, take effect rapidly, have low direct implementation costs, and be reversible in its direct climatic effects. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change concludes that it "is the most-researched [solar geoengineering] method that it could limit warming to below 1.5 °C (2.7 °F)." However, like other solar geoengineering approaches, stratospheric aerosol injection would do so imperfectly and other effects are possible, particularly if used in a suboptimal manner.

Atmospheric methane is the methane present in Earth's atmosphere. The concentration of atmospheric methane is increasing due to methane emissions, and is causing climate change. Methane is one of the most potent greenhouse gases. Methane's radiative forcing (RF) of climate is direct, and it is the second largest contributor to human-caused climate forcing in the historical period. Methane is a major source of water vapour in the stratosphere through oxidation; and water vapour adds about 15% to methane's radiative forcing effect. The global warming potential (GWP) for methane is about 84 in terms of its impact over a 20-year timeframe, and 28 in terms of its impact over a 100-year timeframe.

Climate change feedbacks are natural processes which impact how much global temperatures will increase for a given amount of greenhouse gas emissions. Positive feedbacks amplify global warming while negative feedbacks diminish it. Feedbacks influence both the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere and the amount of temperature change that happens in response. While emissions are the forcing that causes climate change, feedbacks combine to control climate sensitivity to that forcing.

Deglaciation is the transition from full glacial conditions during ice ages, to warm interglacials, characterized by global warming and sea level rise due to change in continental ice volume. Thus, it refers to the retreat of a glacier, an ice sheet or frozen surface layer, and the resulting exposure of the Earth's surface. The decline of the cryosphere due to ablation can occur on any scale from global to localized to a particular glacier. After the Last Glacial Maximum, the last deglaciation begun, which lasted until the early Holocene. Around much of Earth, deglaciation during the last 100 years has been accelerating as a result of climate change, partly brought on by anthropogenic changes to greenhouse gases.

Climate change caused by greenhouse gas emissions from human activities occurs everywhere on Earth, and while Antarctica is less vulnerable to it than any other continent, climate change in Antarctica has already been observed. There has been an average temperature increase of >0.05 °C/decade since 1957 across the continent, although it had been uneven. While West Antarctica warmed by over 0.1 °C/decade from the 1950s to the 2000s and the exposed Antarctic Peninsula has warmed by 3 °C (5.4 °F) since the mid-20th century, the colder and more stable East Antarctica had been experiencing cooling until the 2000s. Around Antarctica, the Southern Ocean has absorbed more heat than any other ocean, with particularly strong warming at depths below 2,000 m (6,600 ft) and around the West Antarctic, which has warmed by 1 °C (1.8 °F) since 1955.

References

- ↑ "University of Reading presented with Queen's Anniversary Prize for climate change work - Wokingham.Today". 2022-02-23. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Singarayer, Joy Sargita (2003). Linearly modulated optically stimulated luminescence of sedimentary quartz : physical mechanisms and implications for dating (Ph.D. thesis). University of Oxford.

- ↑ "About". Joy Singarayer. Retrieved 9 March 2022.

- ↑ Glasser, Neil F.; Jansson, Krister N.; Duller, Geoffrey A. T.; Singarayer, Joy; Holloway, Max; Harrison, Stephan (2016-02-12). "Glacial lake drainage in Patagonia (13-8 kyr) and response of the adjacent Pacific Ocean". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 21064. Bibcode:2016NatSR...621064G. doi:10.1038/srep21064. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4751529 . PMID 26869235.

- ↑ "Catastrophic failure of South American Ice Age dam changed Pacific Ocean circulation and climate". ScienceDaily. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Bristol, University of. "February: Catastrophic failure of ice age dam | News and features | University of Bristol". www.bristol.ac.uk. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Survey, British Antarctic. "New Antarctic ice discovery aids future climate predictions". phys.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Holloway, Max D.; Sime, Louise C.; Singarayer, Joy S.; Tindall, Julia C.; Bunch, Pete; Valdes, Paul J. (2016-08-16). "Antarctic last interglacial isotope peak in response to sea ice retreat not ice-sheet collapse". Nature Communications. 7 (1): 12293. Bibcode:2016NatCo...712293H. doi:10.1038/ncomms12293. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 4990695 . PMID 27526639.

- ↑ Singarayer, Joy S.; Valdes, Paul J.; Friedlingstein, Pierre; Nelson, Sarah; Beerling, David J. (February 2011). "Late Holocene methane rise caused by orbitally controlled increase in tropical sources". Nature. 470 (7332): 82–85. Bibcode:2011Natur.470...82S. doi:10.1038/nature09739. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 21293375. S2CID 4353095.

- ↑ "Orbital mechanics affect methane levels - ABC sydney - Australian Broadcasting Corporation". www.abc.net.au. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Singarayer, Joy S; Ridgwell, Andy; Irvine, Peter (October 2009). "Assessing the benefits of crop albedo bio-geoengineering". Environmental Research Letters. 4 (4): 045110. Bibcode:2009ERL.....4d5110S. doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/4/4/045110 . ISSN 1748-9326. S2CID 3742686.

- ↑ "'Crops could keep Earth cool' say scientists". BBC News. 2010-11-11. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ "Cooling the world with crops | Royal Society". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ "Reflective Crops Could Cool the Planet". NBC News. Archived from the original on March 2, 2021. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Bristol, University of. "2009: The Incredible Human Journey | News and features | University of Bristol". www.bristol.ac.uk. Retrieved 2022-02-28.

- ↑ Simon, Jane (2009-12-07). "Man on Earth". mirror. Retrieved 2022-03-04.

- ↑ "COP26: Climate change graph 'needs more colours' as world gets hotter". BBC News. 2021-11-02. Retrieved 2022-02-28.