The Chumash are a Native American people of the central and southern coastal regions of California, in portions of what is now Kern, San Luis Obispo, Santa Barbara, Ventura and Los Angeles Counties, extending from Morro Bay in the north to Malibu in the south to Mt Pinos in the east. Their territory includes three of the Channel Islands: Santa Cruz, Santa Rosa, and San Miguel; the smaller island of Anacapa was likely inhabited seasonally due to the lack of a consistent water source.

The Tongva are an Indigenous people of California from the Los Angeles Basin and the Southern Channel Islands, an area covering approximately 4,000 square miles (10,000 km2). In the precolonial era, the people lived in as many as 100 villages and primarily identified by their village rather than by a pan-tribal name. During colonization, the Spanish referred to these people as Gabrieleño and Fernandeño, names derived from the Spanish missions built on their land: Mission San Gabriel Arcángel and Mission San Fernando Rey de España. Tongva is the most widely circulated endonym among the people, used by Narcisa Higuera in 1905 to refer to inhabitants in the vicinity of Mission San Gabriel. Some people who identify as direct lineal descendants of the people advocate the use of their ancestral name Kizh as an endonym.

The Channel Islands are an eight-island archipelago located within the Southern California Bight in the Pacific Ocean, off the coast of California. They define the Santa Barbara Channel between the islands and the California mainland. The four Northern Channel Islands are part of the Transverse Ranges geologic province, and the four Southern Channel Islands are part of the Peninsular Ranges province. Five of the islands are within the Channel Islands National Park. The waters surrounding these islands make up Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. The Nature Conservancy was instrumental in establishing the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary.

San Nicolas Island is the most remote of the Channel Islands, off of Southern California, 61 miles (98 km) from the nearest point on the mainland coast. It is part of Ventura County. The 14,562 acre island is currently controlled by the United States Navy and is used as a weapons testing and training facility, served by Naval Outlying Landing Field San Nicolas Island. The uninhabited island is defined by the United States Census Bureau as Block Group 9, Census Tract 36.04 of Ventura County, California. The Nicoleño Native American tribe inhabited the island until 1835. As of the 2000 U.S. Census, the island has since remained officially uninhabited, though the census estimates that at least 200 military and civilian personnel live on the island at any given time. The island has a small airport, though the 10,000 foot (3,000 m) runway is the second longest in Ventura County. Additionally, there are several buildings including telemetry reception antennas.

Santa Barbara Island is a small island of the Channel Islands archipelago in Southern California. It is protected within Channel Islands National Park, and its marine ecosystem is part of the Channel Islands National Marine Sanctuary. Public passenger access to Santa Barbara Island is provided by the Island Packers ferry service.

San Miguel Island is the westernmost of California's Channel Islands, located across the Santa Barbara Channel in the Pacific Ocean, within Santa Barbara County, California. San Miguel is the sixth-largest of the eight Channel Islands at 9,325 acres (3,774 ha), including offshore islands and rocks. Prince Island, 700 m (2,300 ft) off the northeastern coast, measures 35 acres (14 ha) in area. The island, at its farthest extent, is 8 miles (13 km) long and 3.7 miles (6.0 km) wide.

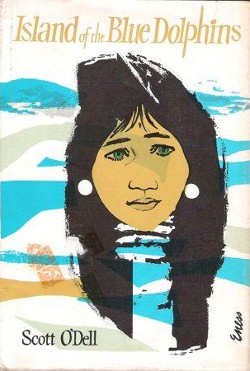

Island of the Blue Dolphins is a 1960 children's novel by American writer Scott O'Dell, which tells the story of a girl named Karana, who is stranded alone for years on an island off the California coast. It is based on the true story of Juana Maria, a Nicoleño Native American left alone for 18 years on San Nicolas Island during the nineteenth century.

The island scrub jay, also known as the island jay or Santa Cruz jay, is a bird in the genus, Aphelocoma, which is endemic to Santa Cruz Island off the coast of Southern California. Of the over 500 breeding bird species in the continental U.S. and Canada, it is the only insular endemic landbird species.

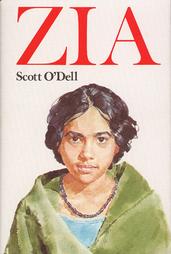

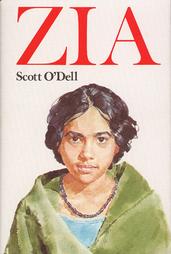

Zia is the sequel to the award-winning Island of the Blue Dolphins by Scott O'Dell. It was published in 1976, sixteen years after the publication of the first novel.

The Nicoleño were the people who lived on San Nicolas Island in California at the time of European contact. They spoke a Uto-Aztecan language. The population of the island was "left devastated by a massacre in 1811 by sea otter hunters." Its last surviving member, who was given the name Juana Maria, was born before 1811 and died in 1853.

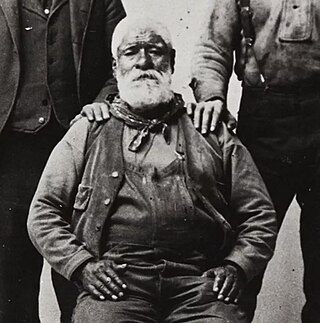

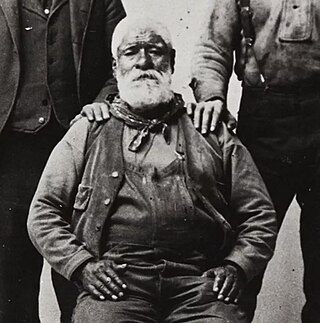

George Nidever was an American mountain man, explorer, fur trapper, memoirist and sailor. In the 1830s he became one of the first wave of American settlers to move to Mexican California, where he made his living in fur trapping. In 1853 he led the expedition that rescued Juana Maria, the last member of the Nicoleño people, from San Nicolas Island where she had been living alone for eighteen years. Toward the end of his life Nidever wrote a memoir, Life and Adventures of George Nidever, which was popular at the end of the 19th century.

Juyubit was one of the largest villages of the Tongva people. The village was located at the foot of the West Coyote Hills at the confluence of the Coyote and La Cañada Verde creeks, in present-day Buena Park and Cerritos. It was one of the largest villages in Tovaangar. Alternate names of the village include: Jujubit, Jutucubit, Jutucuvit, Jutubit, Jutucunga, Utucubit, Otocubit, Uchubit, Ychubit, and Uchunga.

The Nicoleño language is an extinct language formerly spoken on San Nicolas Island by the Nicoleño. It went extinct with Juana Maria's death in 1853. Its extant remnants consist only of four words and two songs attributed to her. This evidence was recorded by non-speakers, as contemporary accounts are clear that no one could be found who could understand Juana Maria. The four Nicoleño words that were translated were tocah, meaning "animal hide"; nache, meaning "man"; toygwah, meaning "sky"; and puoochay, meaning "body".

Zaniolepis frenata, also known as the shortspine combfish, is a species of ray-finned fish belonging to the family Zaniolepididae.The species occurs in the eastern Pacific Ocean.

Yaanga was a large Tongva village, originally located near what is now downtown Los Angeles, just west of the Los Angeles River and beneath U.S. Route 101. People from the village were recorded as Yabit in missionary records although they were known as Yaangavit, Yavitam, or Yavitem among the people. It is unclear what the exact population of Yaanga was prior to colonization, although it was recorded as the largest and most influential village in the region.

Lydia was a US merchant ship that sailed on maritime fur trading ventures in the early 1800s. In December 1813 it was sold to the Russian–American Company and renamed Il'mena, also spelled Ilmena and Il'men'. As both Lydia and Il'mena it was involved in notable events. Today it is best known for its role in an 1814 massacre of the Nicoleño natives of San Nicolas Island, which ultimately resulted in one Nicoleño woman, known as Juana Maria, living alone on the island for many years. These events became the basis for Scott O'Dell's 1960 children's novel Island of the Blue Dolphins and the 1964 film adaptation Island of the Blue Dolphins.

Pajbenga, alternative spelling Pagbigna and Pasbengna, was a Tongva village located at Santa Ana, California, near the El Refugio Adobe, which was the home of José Sepulveda. It was one of the main villages along the Santa Ana River, including Lupukngna, Genga, Totpavit, and Hutuknga. People from the village were recorded in mission records as Pajebet, Pajbet, Pajbebet, and Pajbepet.

Totpavit, alternative spellings Totabit and possibly Totavet, was a Tongva village located in what is now Olive, California. The village was located between the Santa Ana River and Santiago Creek. It was part of a series of villages along the Santa Ana River, including Genga, Pajbenga, and Hutuknga.

Kitsepawit, more commonly known as Fernando Librado, was a Chumash elder, master tomol builder, craft specialist, and storyteller. He was born at Mission San Buenaventura in 1839 as the son of two Chumash parents from the island of Limuw.

Petra Pico was a Chumash basket weaver, elder, and regarded as a figurehead of the Ventureño Chumash Community. She was born at Mission San Buenaventura in 1834 to two Chumash neophytes. Her parents were also born and raised at the Mission and had ties to villages throughout modern-day Ventura County, near Santa Paula and the Santa Monica Mountains.