Show jumping, also known as "stadium jumping", is a part of a group of English riding equestrian events that also includes dressage, eventing, hunters, and equitation. Jumping classes are commonly seen at horse shows throughout the world, including the Olympics. Sometimes shows are limited exclusively to jumpers, sometimes jumper classes are offered in conjunction with other English-style events, and sometimes show jumping is but one division of very large, all-breed competitions that include a very wide variety of disciplines. Jumping classes may be governed by various national horse show sanctioning organizations, such as the United States Equestrian Federation in the USA or the British Showjumping Association in Great Britain. International competitions are governed by the rules of the International Federation for Equestrian Sports. Horses are very well-known for jumping in competition or even freely.

Horses can use various gaits during locomotion across solid ground, either naturally or as a result of specialized training by humans.

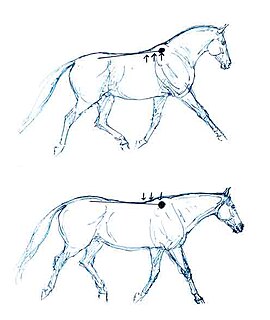

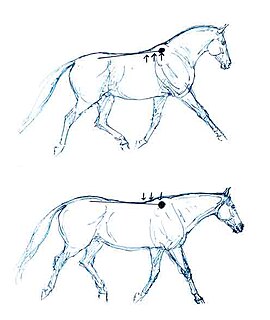

Collection occurs when a horse's center of gravity is shifted backwards. Energy is directed in a more horizontal trajectory with less forward movement. Biomechanical markers include: increased flexion in the lumbo-sacral joint, stifle, and hocks of the horse; increased engagement of the thoracic sling muscles resulting in the withers rising relative to the horse's scapula; and reduced ranges of limb protraction–retraction.

The trot is a two-beat diagonal gait of the horse where the diagonal pairs of legs move forward at the same time with a moment of suspension between each beat. It has a wide variation in possible speeds, but averages about 13 kilometres per hour (8.1 mph). A very slow trot is sometimes referred to as a jog. An extremely fast trot has no special name, but in harness racing, the trot of a Standardbred is faster than the gallop of the average non-racehorse, and has been clocked at over 30 miles per hour (48 km/h).

The canter and gallop are variations on the fastest gait that can be performed by a horse or other equine. The canter is a controlled three-beat gait, while the gallop is a faster, four-beat variation of the same gait. It is a natural gait possessed by all horses, faster than most horses' trot, or ambling gaits. The gallop is the fastest gait of the horse, averaging about 40 to 48 kilometres per hour. The speed of the canter varies between 16 to 27 kilometres per hour depending on the length of the horse's stride. A variation of the canter, seen in western riding, is called a lope, and is generally quite slow, no more than 13–19 kilometres per hour (8–12 mph).

Equine conformation evaluates a horse's bone structure, musculature, and its body proportions in relation to each other. Undesirable conformation can limit the ability to perform a specific task. Although there are several faults with universal disadvantages, a horse's conformation is usually judged by what its intended use may be. Thus "form to function" is one of the first set of traits considered in judging conformation. A horse with poor form for a Grand Prix show jumper could have excellent conformation for a World Champion cutting horse, or to be a champion draft horse. Every horse has good and bad points of its conformation and many horses excel even with conformation faults.

The Hunter division is a branch of horse show competition that is judged on the horse's performance, soundness and when indicated, conformation, suitability or manners. A "show hunter" is a horse that competes in this division.

Equestrianism made its Summer Olympics debut at the 1900 Summer Olympics in Paris, France. It disappeared until 1912, but has appeared at every Summer Olympic Games since. The current Olympic equestrian disciplines are Dressage, Eventing, and Jumping. In each discipline, both individual and team medals are awarded. Women and men compete together on equal terms.

Bascule is the natural round arc a horse's body takes as it goes over a jump. The horse should rise up through its back, stretching its neck forward and down, when it reaches the peak of his jump. Ideally, the withers are the highest point over the fence. This is often described as the horse taking the shape of a dolphin jumping out of the water. Bascule can also refer more generally to the raising of the withers while the horse is in motion.

Captain Federico Caprilli was an Italian cavalry officer and equestrian who revolutionized the jumping seat. His position, now called the "forward seat," formed the modern-day technique used by all jumping riders today.

The pastern is a part of the leg of a horse between the fetlock and the top of the hoof. It incorporates the long pastern bone and the short pastern bone, which are held together by two sets of paired ligaments to form the pastern joint. Anatomically homologous to the two largest bones found in the human finger, the pastern was famously mis-defined by Samuel Johnson in his dictionary as "the knee of a horse". When a lady asked Johnson how this had happened, he gave the much-quoted reply: "Ignorance, madam, pure ignorance."

The jumping position is a position used by equestrians when jumping over an obstacle. It usually involves what is known as the "forward seat" or "2 point" because the rider's legs provide two points over which the rider's weight is balanced on the horse. It was first developed by Captain Federico Caprilli. This involves the rider centered over his or her feet, with the stirrup leathers perpendicular to the ground. Continuing a line upwards from the stirrup leathers, the head and shoulders fall in front of the line, as do the knees, the hips fall behind it.

The skeletal system of the horse has three major functions in the body. It protects vital organs, provides framework, and supports soft parts of the body. Horses typically have 205 bones. The pelvic limb typically contains 19 bones, while the thoracic limb contains 20 bones.

Lameness is an abnormal gait or stance of an animal that is the result of dysfunction of the locomotor system. In the horse, it is most commonly caused by pain, but can be due to neurologic or mechanical dysfunction. Lameness is a common veterinary problem in racehorses, sport horses, and pleasure horses. It is one of the most costly health problems for the equine industry, both monetarily for the cost of diagnosis and treatment, and for the cost of time off resulting in loss-of-use.

Studbook selection is a process used in certain breeds of horses to select breeding stock. It allows a breed registry to direct the evolution of the breed towards the ideal by eliminating unhealthy or undesirable animals from the population. The removal of individuals from a population is called culling, and does not suggest killing the animal in question. Typically, culls are castrated or they and their offspring are unable to be registered.

Various obstacles are found in competitive sports involving horse jumping. These include show jumping, hunter, and the cross-country phase of the equestrian discipline of eventing. The size and type of obstacles vary depending on the course and the level of the horse and rider, but all horses must successfully negotiate these obstacles in order to complete a competition. Fences used in hunter and eventing are generally made to look relatively rustic and natural.

Curb is defined in older literature as enlargement secondary to inflammation and thickening of the long plantar ligament in horses. However, with the widespread use of diagnostic ultrasonography in equine medicine, curb has been redefined as a collection of soft tissue injuries of the distal plantar hock region. Curb is a useful descriptive term when describing swelling in this area.

Lead refers to which set of legs, left or right, leads or advances forward to a greater extent when a quadruped animal is cantering, galloping, or leaping. The feet on the leading side touch the ground forward of its partner. On the "left lead", the animal's left legs lead. The choice of lead is of special interest in horse riding.

The limbs of the horse are structures made of dozens of bones, joints, muscles, tendons, and ligaments that support the weight of the equine body. They include two apparatuses: the suspensory apparatus, which carries much of the weight, prevents overextension of the joint and absorbs shock, and the stay apparatus, which locks major joints in the limbs, allowing horses to remain standing while relaxed or asleep. The limbs play a major part in the movement of the horse, with the legs performing the functions of absorbing impact, bearing weight, and providing thrust. In general, the majority of the weight is borne by the front legs, while the rear legs provide propulsion. The hooves are also important structures, providing support, traction and shock absorption, and containing structures that provide blood flow through the lower leg. As the horse developed as a cursorial animal, with a primary defense mechanism of running over hard ground, its legs evolved to the long, sturdy, light-weight, one-toed form seen today.

The stay apparatus is a group of ligaments, tendons and muscles which "lock" major joints in the limbs of the horse. It is best known as the mechanism by which horses can enter a light sleep while still standing up. It does, however, exist in other large land mammals, where it plays a role in reducing fatigue while standing. The stay apparatus allows animals to relax their muscles and doze without collapsing.