A chromosome is a package of DNA containing part or all of the genetic material of an organism. In most chromosomes, the very long thin DNA fibers are coated with nucleosome-forming packaging proteins; in eukaryotic cells, the most important of these proteins are the histones. Aided by chaperone proteins, the histones bind to and condense the DNA molecule to maintain its integrity. These eukaryotic chromosomes display a complex three-dimensional structure that has a significant role in transcriptional regulation.

Down syndrome or Down's syndrome, also known as trisomy 21, is a genetic disorder caused by the presence of all or part of a third copy of chromosome 21. It is usually associated with developmental delays, mild to moderate intellectual disability, and characteristic physical features.

A trisomy is a type of polysomy in which there are three instances of a particular chromosome, instead of the normal two. A trisomy is a type of aneuploidy.

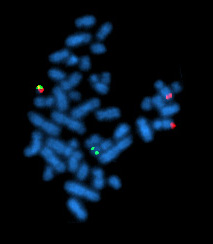

A karyotype is the general appearance of the complete set of chromosomes in the cells of a species or in an individual organism, mainly including their sizes, numbers, and shapes. Karyotyping is the process by which a karyotype is discerned by determining the chromosome complement of an individual, including the number of chromosomes and any abnormalities.

Cytogenetics is essentially a branch of genetics, but is also a part of cell biology/cytology, that is concerned with how the chromosomes relate to cell behaviour, particularly to their behaviour during mitosis and meiosis. Techniques used include karyotyping, analysis of G-banded chromosomes, other cytogenetic banding techniques, as well as molecular cytogenetics such as fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH).

In genetics, chromosome translocation is a phenomenon that results in unusual rearrangement of chromosomes. This includes balanced and unbalanced translocation, with two main types: reciprocal, and Robertsonian translocation. Reciprocal translocation is a chromosome abnormality caused by exchange of parts between non-homologous chromosomes. Two detached fragments of two different chromosomes are switched. Robertsonian translocation occurs when two non-homologous chromosomes get attached, meaning that given two healthy pairs of chromosomes, one of each pair "sticks" and blends together homogeneously.

Irene Ayako Uchida, was a Canadian scientist and Down syndrome researcher.

The year 1958 in science and technology involved some significant events, listed below.

Polysomy is a condition found in many species, including fungi, plants, insects, and mammals, in which an organism has at least one more chromosome than normal, i.e., there may be three or more copies of the chromosome rather than the expected two copies. Most eukaryotic species are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes, whereas prokaryotes are haploid, containing a single chromosome in each cell. Aneuploids possess chromosome numbers that are not exact multiples of the haploid number and polysomy is a type of aneuploidy. A karyotype is the set of chromosomes in an organism and the suffix -somy is used to name aneuploid karyotypes. This is not to be confused with the suffix -ploidy, referring to the number of complete sets of chromosomes.

Chromosome 13 is one of the 23 pairs of chromosomes in humans. People normally have two copies of this chromosome. Chromosome 13 spans about 113 million base pairs and represents between 3.5 and 4% of the total DNA in cells.

A dicentric chromosome is an abnormal chromosome with two centromeres. It is formed through the fusion of two chromosome segments, each with a centromere, resulting in the loss of acentric fragments and the formation of dicentric fragments. The formation of dicentric chromosomes has been attributed to genetic processes, such as Robertsonian translocation and paracentric inversion. Dicentric chromosomes have important roles in the mitotic stability of chromosomes and the formation of pseudodicentric chromosomes. Their existence has been linked to certain natural phenomena such as irradiation and have been documented to underlie certain clinical syndromes, notably Kabuki syndrome. The formation of dicentric chromosomes and their implications on centromere function are studied in certain clinical cytogenetics laboratories.

A chromosomal abnormality, chromosomal anomaly, chromosomal aberration, chromosomal mutation, or chromosomal disorder is a missing, extra, or irregular portion of chromosomal DNA. These can occur in the form of numerical abnormalities, where there is an atypical number of chromosomes, or as structural abnormalities, where one or more individual chromosomes are altered. Chromosome mutation was formerly used in a strict sense to mean a change in a chromosomal segment, involving more than one gene. Chromosome anomalies usually occur when there is an error in cell division following meiosis or mitosis. Chromosome abnormalities may be detected or confirmed by comparing an individual's karyotype, or full set of chromosomes, to a typical karyotype for the species via genetic testing.

Patricia Ann Jacobs is a Scottish geneticist and is Honorary Professor of Human Genetics, Co-director of Research, Wessex Regional Genetics Laboratory, within the University of Southampton.

Rex Brinkworth MBE was the founder of the UK Down's Syndrome Association. He was a pioneer of early treatment for babies with Down syndrome through stimulation and diet. He collaborated on this with Jerome Lejeune, the French geneticist who discovered that Down syndrome is caused by an extra chromosome 21. He was also a campaigner for integrated mainstream education for children with Down syndrome, and against the use of term 'mongolism' to refer to the syndrome. By coincidence, later he and his wife themselves had a child with Down syndrome.

Marthe Gautier was a French medical doctor and researcher, best known for her role in discovering the link of diseases to chromosome abnormalities.

Raymond Alexander Turpin, born 5 November 1895 in Pontoise, died May 24, 1988, in Paris, was a French pediatrician and geneticist. In the late 1950s, his team discovered the chromosomal abnormality, trisomy 21, responsible for Down syndrome.

William Rees Brebner Robertson was an American zoologist and early cytogeneticist who discovered the chromosomal rearrangement named in his honour, Robertsonian translocation, the most common structural chromosomal abnormalities seen in humans that result in syndromes of multiple malformations, including trisomy 13 Patau syndrome and trisomy 21 Down syndrome.

Trisomy X, also known as triple X syndrome and characterized by the karyotype 47,XXX, is a chromosome disorder in which a female has an extra copy of the X chromosome. It is relatively common and occurs in 1 in 1,000 females, but is rarely diagnosed; fewer than 10% of those with the condition know they have it.

Grant Robert Sutherland is a retired Australian human geneticist and cytogeneticist. He was the Director, Department of Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics, Adelaide Women's and Children's Hospital for 27 years (1975-2002), then became the Foundation Research Fellow there until 2007. He is an Emeritus Professor in the Departments of Paediatrics and Genetics at the University of Adelaide.