Anak Agung Pandji Tisna, also known as Anak Agung Nyoman Pandji Tisna, I Gusti Nyoman Pandji Tisna, or just Pandji Tisna, was the 11th descendant of the Pandji Sakti dynasty of Buleleng, Singaraja, which is in the northern part of Bali, Indonesia. He succeeded his father, Anak Agung Putu Djelantik, in 1944.

Subagio Sastrowardoyo was an Indonesian poet, short-story writer, essayist and literary critic. Born in Madiun, East Java, the Dutch East Indies, he studied at Gadjah Mada University, Cornell University and in 1963 graduated with an MA from Yale University. His debut as a writer came early with the publication of Simphoni (Symphony), a collection of poems, in 1957. The collection has been described as "cynical, untamed poetry, shocking sometimes". Simphoni was followed by several attempts at short story writing, including the publication Kedjananan di Sumbing, before Subagio settled on poetry as his main creative outlet. Following an extended stay in the United States he published a collection of poems entitled Saldju (Snow) in 1966. The poems in this collection deal with questions of life and death, and of the need for "something to hold on to in an existence threatened on all sides", and have been described as altogether more restrained than those in his earlier work. Additional works published since 1966 include Daerab Perbatasan (1970), Keroncong Motinggo (1975), Buku Harian (Diary), Hari dan Hara (1979)Simphoni Dua (1990), and several books of literary criticism. Subagio's collected poems have been published as Dan Kematian Makin Akrab (1995).

Indonesian literature is a term grouping various genres of South-East Asian literature.

Marah Roesli was an Indonesian writer.

Balai Pustaka is the state-owned publisher of Indonesia and publisher of major pieces of Indonesian literature such as Salah Asuhan, Sitti Nurbaya and Layar Terkembang. Its head office is in Jakarta.

Hans Bague Jassin, better known as HB Jassin, was an Indonesian literary critic, documentarian, and professor. Born in Gorontalo to a bibliophilic petroleum company employee, Jassin began reading while still in elementary school, later writing published reviews before finishing high school. After a while working in the Gorontalo regent's office, he moved to Jakarta where he worked at the state publisher Balai Pustaka. After leaving the publisher, he attended the University of Indonesia and later Yale. Returning to Indonesia to be a teacher, he also headed Sastra magazine. Horison, a literary magazine, was started in July 1966 by Jassin and Mochtar Lubis as a successor to Sastra, and was edited by Taufiq Ismail, Ds. Muljanto, Zaini, Su Hok Djin, and Goenawan Mohamad. In 1971, Jassin was given a one-year prison sentence and a two-year probation period because as the editor of Sastra, he refused to reveal the identity of an anonymous writer who wrote a story which was considered by the court to be blasphemous.

Ajip Rosidi was an Indonesian poet and short story writer. As of 1983 he had published 326 works in 22 different magazines.

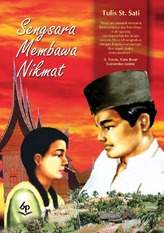

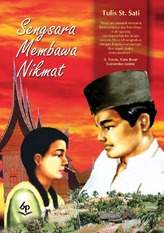

Sengsara Membawa Nikmat is an Indonesian novel written by Tulis Sutan Sati. It was published in 1929 by Balai Pustaka. It tells the story of Midun, the son of a farmer, who experiences many trials before finally living happily with his new wife. It has been noted as one of Sati's most interesting works.

Christophorus Apolinaris Eka Budianta Martoredjo, also known as C. A. Eka Budianta, more commonly known as Eka Budianta is an Indonesian poet. He was born into a Catholic family and was the second child of nine. His grandparents were farmers. His parents were public elementary school teachers; his father later worked at the local office for the Ministry Education and his mother became a school principal. After graduating from St. Albertus high school in Malang (Dempo), he attended the Lembaga Pendidikan Kesenian Jakarta, now known as Institut Kesenian Jakarta, but did not complete his studies. From 1975 to 1979, Eka Budianta studied Japanese literature at the Department of East Asian Studies Literature; he then moved to the Department of History at the University of Indonesia. He subsequently studied journalism at Los Angeles Trade-Technical College in the United States from 1980–81. He also worked as a reporter for Tempo weekly newsmagazine and the Japanese newspaper Yomiuri Shimbun.

Armijn Pane, also known as Adinata, A. Soul, Empe, A. Mada, A. Banner, and Kartono, was an Indonesian author.

Tengku Amir Hamzah was an Indonesian poet and National Hero of Indonesia. Born into a Malay aristocratic family in the Sultanate of Langkat in North Sumatra, he was educated in both Sumatra and Java. While attending senior high school in Surakarta around 1930, Amir became involved with the nationalist movement and fell in love with a Javanese schoolmate, Ilik Sundari. Even after Amir continued his studies in legal school in Batavia the two remained close, only separating in 1937 when Amir was recalled to Sumatra to marry the sultan's daughter and take on responsibilities of the court. Though unhappy with his marriage, he fulfilled his courtly duties. After Indonesia proclaimed its independence in 1945, he served as the government's representative in Langkat. The following year he was killed in a social revolution led by the PESINDO, and buried in a mass grave.

Poedjangga Baroe was an Indonesian avant-garde literary magazine published from July 1933 to February 1942. It was founded by Armijn Pane, Amir Hamzah, and Sutan Takdir Alisjahbana.

I Wayan Gobiah was a Balinese teacher and writer. He is best known for Nemoe Karma, a 1931 novel which is considered the first Balinese-language novel.

Zuber Usman was an Indonesian teacher and writer, known as an early pioneer of Indonesian literary criticism. Born in Padang, West Sumatra, he was educated in Islamic schools until 1937, after which he became a teacher. Dabbling in writing short stories during the Japanese occupation of the Dutch East Indies and the ensuing revolution, for the rest of his life Usman focused on teaching and writing about literature.

Sariamin Ismail was the first female Indonesian novelist to be published in the Dutch East Indies. A teacher by trade, by the 1930s she had begun writing in newspapers; she published her first novel, Kalau Tak Untung, in 1933. She published two novels and several poetry anthologies afterwards, while continuing to teach and – between 1947 and 1949 – serving as a member of the regional representative body in Riau. Her literary works often dealt with star-crossed lovers and the role of fate, while her editorials were staunchly anti-polygamy. She was one of only a handful of Indonesian women authors to be published at all during the colonial period, alongside Fatimah Hasan Delais, Saadah Alim, Soewarsih Djojopoespito and a few others.

Soeman Hasibuan better known by his pen name Soeman Hs, was an Indonesian author recognized for pioneering detective fiction and short story writing in the country's literature. Born in Bengkalis, Riau, Dutch East Indies, to a family of farmers, Soeman studied to become a teacher and, under the author Mohammad Kasim, a writer. He began working as a Malay-language teacher after completing normal school in 1923, first in Siak Sri Indrapura, Aceh, then in Pasir Pengaraian, Rokan Hulu, Riau. Around this time he began writing, publishing his first novel, Kasih Tak Terlarai, in 1929. In twelve years he published five novels, one short story collection, and thirty-five short stories and poems.

Muhammad Kasim was an elementary school teacher and writer in the Dutch East Indies who published several books. His short story collection Teman Doedoek is considered the first short story collection in the Indonesian literary canon.

Fatimah Hasan Delais (1915-1953), also known by the pen name Hamidah, was an Indonesian novelist and poet. Her novel Kehilangan mestika, 1935, was among the first by a female author to be published by Balai Pustaka; she was one of only a handful of Indonesian women authors to be published at all in the Dutch East Indies, alongside Saadah Alim, Sariamin Ismail, Soewarsih Djojopoespito and a few others.

Saadah Alim (1897–1968) was a writer, playwright, translator, journalist and educator in the Dutch East Indies and in Indonesia after independence. She was one of only a handful of Indonesian women authors to be published during the colonial period, alongside Fatimah Hasan Delais, Sariamin Ismail, Soewarsih Djojopoespito and a few others. She is known primarily for her journalism, her collection of short stories Taman Penghibur Hati (1941), and her comedic play Pembalasannya (1940).