A green card, known officially as a permanent resident card, is an identity document which shows that a person has permanent residency in the United States. Green card holders are formally known as lawful permanent residents (LPRs). As of 2019, there are an estimated 13.9 million green card holders, of whom 9.1 million are eligible to become United States citizens. Approximately 18,700 of them serve in the U.S. Armed Forces.

An O visa is a classification of non-immigrant temporary worker visa granted by the United States to an alien "who possesses extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics, or who has a demonstrated record of extraordinary achievement in the motion picture or television industry and has been recognized nationally or internationally for those achievements", and to certain assistants and immediate family members of such aliens.

A K-1 visa is a visa issued to the fiancé or fiancée of a United States citizen to enter the United States. A K-1 visa requires a foreigner to marry his or her U.S. citizen petitioner within 90 days of entry, or depart the United States. Once the couple marries, the foreign citizen can adjust status to become a lawful permanent resident of the United States. Although a K-1 visa is legally classified as a non-immigrant visa, it usually leads to important immigration benefits and is therefore often processed by the Immigrant Visa section of United States embassies and consulates worldwide.

U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) is an agency of the United States Department of Homeland Security (DHS) that administers the country's naturalization and immigration system. It is a successor to the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS), which was dissolved by the Homeland Security Act of 2002 and replaced by three components within the DHS: USCIS, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and Customs and Border Protection (CBP).

A Request for Evidence (RFE) is a request issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to petitioners for residency, citizenship, family visas, and employment visas. Examples of petitions for which a RFE may be issued are Form I-129, Form I-140, and Form I-130.

The EB-1 visa is a preference category for United States employment-based permanent residency. It is intended for "priority workers". Those are foreign nationals who either have "extraordinary abilities", or are "outstanding professors or researchers", and also includes "some executives and managers of foreign companies who are transferred to the US". It allows them to remain permanently in the US.

EB-2 is an immigrant visa preference category for United States employment-based permanent residency, created by the Immigration Act of 1990. The category includes "members of the professions holding advanced degrees or their equivalent", and "individuals who because of their exceptional ability in the sciences, arts, or business will substantially benefit prospectively the national economy, cultural or educational interests, or welfare of the United States, and whose services in the sciences, arts, professions, or business are sought by an employer in the United States". Applicants must generally have an approved labor certification, a job offer, and their employer must have filed an Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker with the USCIS.

Alien of extraordinary ability is an alien classification by United States Citizenship and Immigration Services. The United States may grant a priority visa to an alien who is able to demonstrate "extraordinary ability in the sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics" or through some other extraordinary career achievements.

Bernard P. Wolfsdorf is an American immigration lawyer, and former President of the American Immigration Lawyers Association (AILA). He is the founder and Managing Partner of Wolfsdorf Immigration Law Group, located in Los Angeles and New York.

Premium Processing Service is an optional premium service offered by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to employers filing Form I-129 or Form I-140. To avail of the service, the employer needs to file Form I-907 and include a fee that is $1,500 for the H-2B and R classifications and $2,500 for all others.

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) issues a number of forms for people to submit to them relating to immigrant and non-immigrant visa statuses. These forms begin with the letter "I". None of the forms directly grants a United States visa, but approval of these forms may provide authorization for staying or extending one's stay in the United States as well as authorization for work. Some United States visas require an associated approved USCIS immigration form to be submitted as part of the application.

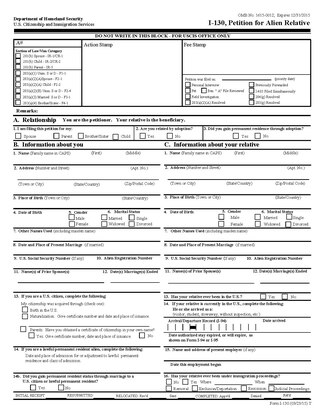

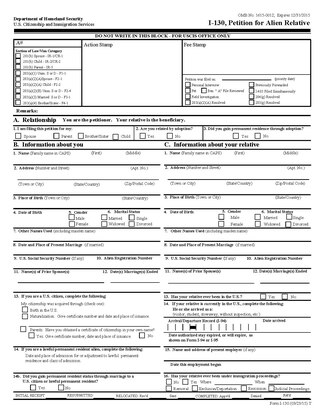

Form I-130, Petition for Alien Relative is a form submitted to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services by a United States citizen or Lawful Permanent Resident petitioning for an immediate or close relative intending to immigrate to the United States. It is one of numerous USCIS immigration forms. As with all USCIS petitions, the person who submits the petition is called the petitioner and the relative on whose behalf the petition is made is called the beneficiary. The USCIS officer who evaluates the petition is called the adjudicator.

A Notice of Intent to Deny (NOID) is a notice issued by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to petitioners for residency, citizenship, family visas, and employment visas. Examples of petitions for which a NOID may be issued are Form I-129, Form I-140, and Form I-130.

Consular nonreviewability refers to the doctrine in immigration law in the United States where the visa decisions made by United States consular officers cannot be appealed in the United States judicial system. It is closely related to the plenary power doctrine that immunizes from judicial review the substantive immigration decisions of the United States Congress and the executive branch of the United States government.

A Notice of Intent to Revoke (NOIR) is a communication sent by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services to a petitioner about a previously approved petition, telling him or her that the USCIS intends to revoke the petition, along with the reasons for revocation, and giving the petitioner a fixed amount of time to respond. NOIRs may be issued for immigrant visa petitions and for non-immigrant visa petitions.

The National Visa Center (NVC) is a center that is part of the U.S. Department of State that plays the role of holding United States immigrant visa petitions approved by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services until an immigrant visa number becomes available for the petition, at which point it arranges for the visa applicant(s) to take the visa interview at a consulate abroad. It is located in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. It was established on July 26, 1994, on the site of an Air Force base that was closed down by The Pentagon.

Form I-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker is a form submitted to the United States Citizenship and Immigration Service (USCIS) by a prospective employer to petition an alien to work in the US on a permanent basis. This is done in the case when the worker is deemed extraordinary in some sense or when qualified workers do not exist in the US. The employer who files is called the petitioner, and the alien employee is called the beneficiary; these two can coincide in the case of a self-petitioner. The form is 6 pages long with a separate 10-page instructions document as of 2016. It is one of the USCIS immigration forms.

A National Interest Waiver is an exemption from the labor certification process and job offer requirement for advanced degree/exceptional ability workers applying for an EB-2 Visa for Immigration into the United States.

The Administrative Appeals Office, full name USCIS Administrative Appeals Office, and also known as the AAO and USCIS AAO, is an office within United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that can be used by petitioners to appeal adverse USCIS decisions made on their petitions. It is located in Washington, D.C., and all its in-person functions happen only in Washington, D.C.

Tenrec v. USCIS, colloquially known as the H-1B Lottery Lawsuit, was a class action lawsuit brought against United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, challenging the lottery process used to decide which cap-subject H-1B Form I-129 petitions to adjudicate in case more petitions were received than the cap for the fiscal year. The plaintiffs were two pairs of H-1B petitioner (employer) and beneficiary. The case was decided against the plaintiffs, and an appeal was withdrawn after both plaintiffs withdrew.