Bunyoro, also called Bunyoro-Kitara, is a traditional Bantu kingdom in Western Uganda. It was one of the most powerful kingdoms in Central and East Africa from the 16th century to the 19th century. It is ruled by the King (Omukama) of Bunyoro-Kitara. The current ruler is Solomon Iguru I, the 27th Omukama.

The ruins of Gedi are a UNESCO World Heritage site near the Indian Ocean coast of eastern Kenya. The site is adjacent to the town of Gedi in the Kilifi District and within the Arabuko-Sokoke Forest.

Ras Hafun, also known as Cape Hafun, is a promontory in the northeastern Bari region of the Puntland state in Somalia.

Arikamedu is an archaeological site in Southern India, in Kakkayanthope, Ariyankuppam Commune, Puducherry. It is 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) from the capital, Pondicherry of the Indian territory of Puducherry.

The Tongoni Ruins are a 15th century Swahili ruins of a mosque and forty tombs located in Tongoni ward in Tanga District inside Tanga Region of Tanzania. The largest and possibly most significant Swahili site in Tanzania is Tongoni, which is located 25 km north of the Pangani River. Overlooking Mtangata Bay, about forty standing tombs and a Friday mosque of the "northern" style occupy a third of a hectare. People from the area continue to worship there spiritually. They bury their departed family members to the south of the historic tombs. The area was a different place four to five centuries ago. Contrary to its almost unnoticed presence today, it was a prosperous and a respected Swahili trading centre during the 15th century. Most of the ruins are still not yet been uncovered. The site is a registered National Historic Site.

Ing'ombe Ilede is an archaeological site located on a hill near the confluence of the Zambezi and Lusitu rivers, near the town of Siavonga, in Zambia. Ing'ombe Ilede, meaning "a sleeping cow", received its name from a local baobab tree that is partially lying on the ground and resembles a sleeping cow from a distance. The site is thought to have been a small commercial state around the 16th century whose chief item of trade was salt. Ing'ombe Ilede received various goods from the hinterland of south-central Africa, such as, copper, slaves, gold and ivory. These items were exchanged with glass beads, cloth, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean trade. The status of Ing'ombe Ilede as a trading center that connected different places in south-central Africa has made it a very important archaeological site in the region.

Mumba Cave, located near the highly alkaline Lake Eyasi in Karatu District, Arusha Region, Tanzania. The cave is a rich archaeological site noted for deposits spanning the transition between the Middle Stone Age and Late Stone Age in Eastern Africa. The transitional nature of the site has been attributed to the large presence of its large assemblage of ostrich eggshell beads and more importantly, the abundance of microlith technology. Because these type artifacts were found within the site it has led archaeologists to believe that the site could provide insight into the origins of modern human behavior. The cave was originally tested by Ludwig Kohl-Larsen and his wife Margit in their 1934 to 1936 expedition. They found abundant artifacts, rock art, and burials. However, only brief descriptions of these findings were ever published. That being said, work of the Kohl-Larsens has been seen as very accomplished due to their attention to detail, especially when one considers that neither was versed in proper archaeological techniques at the time of excavation. The site has since been reexamined in an effort to reanalyze and complement the work that has already been done, but the ramifications of improper excavations of the past are still being felt today, specifically in the unreliable collection of C-14 data and confusing stratigraphy.

Tas-Silġ is a rounded hilltop on the south-east coast of the island of Malta, overlooking Marsaxlokk Bay, and close to the town of Żejtun. Tas-Silġ is a major multi-period sanctuary site with archaeological remains covering 4,000 years, from the neolithic to the ninth century AD. The site includes a megalithic temple complex dating from the early third millennium BC, to a Phoenician and Punic sanctuary dedicated to the goddess Astarte. During the Roman era, the site became an international religious complex dedicated to the goddess Juno, helped by its location along major maritime trading routes, with the site being mentioned by first-century BC orator Cicero.

Unguja Ukuu is a historic Swahili settlement on Unguja island, in Zanzibar, Tanzania.

Kʼaxob is an archaeological site of the Maya civilization located in Belize. It was occupied from about 800 B.C. to A.D. 900. The site is located in northern Belize in the wetlands of Pulltrouser Swamp in proximity to the Sibun River Valley in central Belize. Research has shown that Kʼaxob was occupied from the Late Preclassic Period to the Early Postclassic Period. This period in time and the site is characterized by specific ceramic types as well as agriculture and an increase in social stratification. Kʼaxob is a village site centered on two pyramid plazas and later grew in size during the Early Classic Period to the Late Classic Period. The site includes a number of household, mounds and plazas. Kʼaxob is mostly based on residential and household living but also has some ritualistic aspects.

Knap Hill lies on the northern rim of the Vale of Pewsey, in northern Wiltshire, England, about a mile north of the village of Alton Priors. At the top of the hill is a causewayed enclosure, a form of Neolithic earthwork that was constructed in England from about 3700 BC onwards, characterized by the full or partial enclosure of an area with ditches that are interrupted by gaps, or causeways. Their purpose is not known: they may have been settlements, or meeting places, or ritual sites of some kind. The site has been scheduled as an ancient monument.

Bigo bya Mugenyi also known as just Bigo (“city”), is an extensive alignment of ditches and berms comprising ancient earthworks located in the interlacustrine region of southwestern Uganda. Situated on the southern shore of the Katonga River, Bigo is best described as having two elements. The first consists of a long, irregular ditch and bank alignment with multiple openings that effectively creates an outer boundary by connecting to the Katonga River in the east and the Kakinga swamp to the west. Toward its eastern end the outer ditch branches further to the east to encompass a nearby crossing of the Katonga River. The second element consists of a central, interconnected group of four irregularly shaped ditch and bank enclosures that are connected to the Katonga River by a single ditch. Three mounds are associated with the central enclosures; two within and one immediately to the west. When combined, the Bigo earthworks extend for more than 10 kilometers. Resulting from radiometric dates collected from archaeological investigations conducted in 1960 and additional investigations undertaken at the Mansa earthworks site in 1988, 1994, and 1995, the Bigo earthworks have been dated to roughly AD 1300-1500, and have been called Uganda's "largest and most important ancient monument."

Ntusi is a Late Iron Age archaeological site located in southwestern Uganda that dates from the tenth century to the fifteenth century AD. Ntusi is dominated by two large mounds and manmade scraped valley basins called, bwogero. Long abandoned by the time Hima herdsman grazed their cattle on the Bwera, the herdsman named the site "Ntusi" meaning, "the mounds", after the prominent earthworks. The archaeological record at Ntusi is unmistakable in the signs of intense occupation and activity and it represents the beginning of political complexity in this region of Africa. Bigo bya Mugenyi, another site with prominent earthworks, lies 13 km to the north of Ntusi.

The Gwisho hot-springs are an archaeological site in Lochinvar National Park, Zambia. The location is a rare site for its large quantity of preserved animal and plants remains. The site was first excavated by J. Desmond Clark in 1957, who found faunal remains and quartz tools in the western end of the site.

Shanga is an archaeological site located in Pate Island off the eastern coast of Africa. The site covers about 15 hectares. Shanga was excavated during an eight-year period in which archaeologists examined Swahili origins. The archaeological evidence in the form of coins, pottery, glass and beads all suggest that a Swahili community inhabited the area during the eighth century. Evidence from the findings also indicates that the site was a Muslim trading community that had networks in Asia.

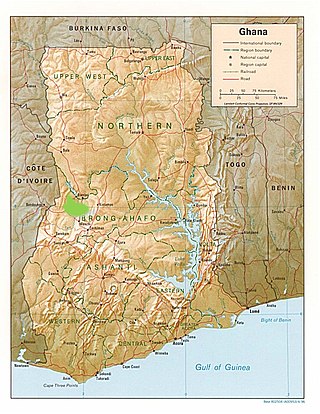

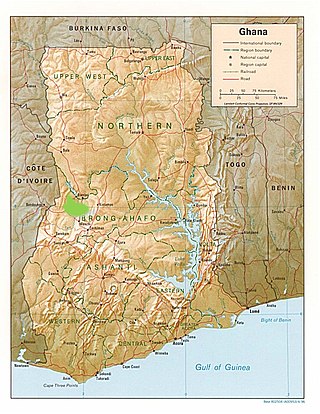

Banda District in Ghana plays an important role in the understanding of trade networks and the way they shaped the lives of people living in western Africa. Banda District is located in West Central Ghana, just south of the Black Volta River in a savanna woodland environment. This region has many connections to trans-Saharan trade, as well as Atlantic trade and British colonial and economic interests. The effects of these interactions can be seen archaeologically through the presence of exotic goods and export of local materials, production of pottery and metals, as well as changes in lifestyle and subsistence patterns. Pioneering archaeological research in this area was conducted by Ann Stahl.

This page is a glossary of archaeology, the study of the human past from material remains.

The Carcajou Point site is located in Jefferson County, Wisconsin, on Lake Koshkonong. It is a multi-component site with prehistoric Upper Mississippian Oneota and Historic components.

Torbulok is an archaeological site located in a foothill zone 50 km northwest of the Kyzylsu river valley and 20 km southeast of Danghara in the south of present-day Tajikistan. The site lies at the foot of the Čaltau mountain range. It was the site of a small sanctuary during the Hellenistic period, when the area was part of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom.

Daima is a mound settlement located in Nigeria, near Lake Chad, and about 5 kilometers away from the Nigerian frontier with Cameroon. It was first excavated in 1965 by British archaeologist Graham Connah. Radiocarbon dating showed the occupations at Daima cover a period beginning early in the first millennium BC, and ending early in the second millennium AD. The Daima sequence then covers some 1800 years. Daima is a perfect example of an archaeological tell site, as Daima’s stratigraphy seems to be divided into three periods or phases which mark separate occupations. These phases are called Daima I, Daima II, and Daima III. Although these occupations differ from each other in multiple ways, they also have some shared aspects with one another. Daima I represents an occupation of a people without metalwork; Daima II is characterized by the first iron-using people of the site; and Daima III represents a rich society with a much more complex material culture.