Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is the same, regardless of the species of origin, but ivory contains structures of mineralised collagen. The trade in certain teeth and tusks other than elephant is well established and widespread; therefore, "ivory" can correctly be used to describe any mammalian teeth or tusks of commercial interest which are large enough to be carved or scrimshawed.

Walrus ivory, also known as morse, comes from two modified upper canines of a walrus. The tusks grow throughout the life and the tusks of a Pacific walrus may attain a length of one meter. Walrus teeth are also commercially carved and traded; the average walrus tooth has a rounded, irregular peg shape and is approximately 5 cm in length.

A netsuke is a miniature sculpture, originating in 17th century Japan. Initially a simply-carved button fastener on the cords of an inro box, netsuke later developed into ornately sculpted objects of craftsmanship.

African art describes the modern and historical paintings, sculptures, installations, and other visual culture from native or indigenous Africans and the African continent. The definition may also include the art of the African diasporas, such as: African American, Caribbean or art in South American societies inspired by African traditions. Despite this diversity, there are unifying artistic themes present when considering the totality of the visual culture from the continent of Africa.

The Benin Bronzes are a group of several thousand metal plaques and sculptures that decorated the royal palace of the Kingdom of Benin in what is now Edo State, Nigeria. Collectively, the objects form the best examples of Benin art and were created from the thirteenth century by artists of the Edo people. Apart from the plaques, other sculptures in brass or bronze include portrait heads, jewellery and smaller pieces.

Scrimshaw is scrollwork, engravings, and carvings done in bone or ivory. Typically it refers to the artwork created by whalers, engraved on the byproducts of whales, such as bones or cartilage. It is most commonly made out of the bones and teeth of sperm whales, the baleen of other whales, and the tusks of walruses. It takes the form of elaborate engravings in the form of pictures and lettering on the surface of the bone or tooth, with the engraving highlighted using a pigment, or, less often, small sculptures made from the same material. However, the latter really fall into the categories of ivory carving, for all carved teeth and tusks, or bone carving. The making of scrimshaw probably began on whaling ships in the late 18th century and survived until the ban on commercial whaling. The practice survives as a hobby and as a trade for commercial artisans. A maker of scrimshaw is known as a scrimshander. The word first appeared in the logbook of the brig By Chance in 1826, but the etymology is uncertain.

Ivory carving is the carving of ivory, that is to say animal tooth or tusk, generally by using sharp cutting tools, either mechanically or manually.

Most African sculpture was historically in wood and other organic materials that have not survived from earlier than at most a few centuries ago; older pottery figures are found from a number of areas. Masks are important elements in the art of many peoples, along with human figures, often highly stylized. There is a vast variety of styles, often varying within the same context of origin depending on the use of the object, but wide regional trends are apparent; sculpture is most common among "groups of settled cultivators in the areas drained by the Niger and Congo rivers" in West Africa. Direct images of African deities are relatively infrequent, but masks in particular are or were often made for traditional African religious ceremonies; today many are made for tourists as "airport art". African masks were an influence on European Modernist art, which was inspired by their lack of concern for naturalistic depiction.

Benin art is the art from the Kingdom of Benin or Edo Empire (1440–1897), a pre-colonial African state located in what is now known as the Southern region of Nigeria. Primarily made of cast bronze and carved ivory, Benin art was produced mainly for the court of the Oba of Benin – a divine ruler for whom the craftsmen produced a range of ceremonially significant objects. The full complexity of these works can be appreciated through the awareness and consideration of two complementary cultural perceptions of the art of Benin: the Western appreciation of them primarily as works of art, and their understanding in Benin as historical documents and as mnemonic devices to reconstruct history, or as ritual objects. This original significance is of great importance in Benin.

The Gebel el-Arak Knife, also Jebel el-Arak Knife, is an ivory and flint knife dating from the Naqada II period of Egyptian prehistory, showing Mesopotamian influence. The knife was purchased in 1914 in Cairo by Georges Aaron Bénédite for the Louvre, where it is now on display in the Sully wing, room 633. At the time of its purchase, the knife handle was alleged by the seller to have been found at the site of Gebel el-Arak, but it is today believed to come from Abydos.

The Yoruba of West Africa are responsible for one of the finest artistic traditions in Africa, a tradition that remains vital and influential today.

Ikegobo, the Edo term for "altars to the Hand," are a type of cylindrical sculpture from the Benin Empire. Used as a cultural marker of an individual's accomplishments, Ikegobo are dedicated to the hand, from which the people of Benin considered the will for wealth and success to originate. These commemorative objects are made of wood or brass with figures carved in relief around their sides.

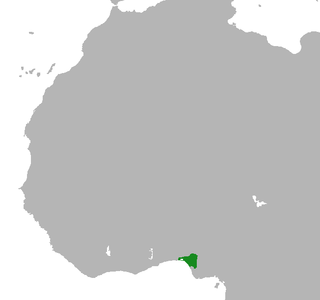

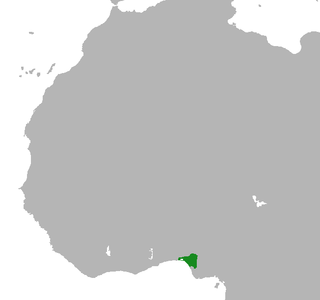

The Kingdom of Benin, also known as the Edo Kingdom, or the Benin Empire was a kingdom within what is now south-south Nigeria. It has no historical relation to the modern republic of Benin, which was known as Dahomey from the 17th century until 1975. The Kingdom of Benin's capital was Edo, now known as Benin City in Edo State, Nigeria. The Benin Kingdom was "one of the oldest and most developed states in the coastal hinterland of West Africa". It grew out of the previous Edo Kingdom of Igodomigodo around the 11th century AD, and lasted until it was annexed by the British Empire in 1897.

Benin ancestral altars are adorned with some of the finest examples of art from the Benin Kingdom of south-central Nigeria.

Some African objects had been collected by Europeans for centuries, and there had been industries producing some types, especially carvings in ivory, for European markets in some coastal regions. Between 1890 and 1918 the volume of objects greatly increased as Western colonial expansion in Africa led to the removal of many pieces of sub-Saharan African art that were subsequently brought to Europe and displayed. These objects entered the collections of natural history museums, art museums and private collections in Europe and the United States. About 90% of Africa's cultural heritage is believed to be located in Europe, according to French art historians.

Carved elephant tusk depicting Buddha life stories is an intricately carved complete single tusk now exhibited at the Decorative Arts gallery, National Museum, New Delhi, India. This tusk was donated to the Museum. This tusk, which is nearly five foot long, illustrates forty three events in the life of the Buddha and is thought to have been made by early 20th century craftsmen from the Delhi region.

The Benin ivory mask is a miniature sculptural portrait in ivory of Idia, the first Iyoba of the 16th century Benin Empire, taking the form of a traditional African mask. The masks were looted by the British from the palace of the Oba of Benin in the Benin Expedition of 1897.

The collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art contains a lidded saltceller. Crafted in either 15th or 16th century Sierra Lione, the item is on view at The Met Fifth Avenue in Gallery 352.

The Sapi-Portuguese Ivory Spoon was created by an unknown Sapi artist in the 16th century. The carving that makes up part of the handle of the spoon was based on European iconography but the design reflects the stylistic traditions of the Sapi people of West Africa.

The Saltcellar with Portuguese Figures is a salt cellar in carved ivory, made in the Kingdom of Benin in West Africa in the 16th century, for the European market. It is attributed to an unknown master or workshop who has been given the name Master of the Heraldic Ship by art historians. It depicts four Portuguese figures, two of higher class and the other two are possibly guards protecting them. In the 16th century Portuguese visitors ordered ivory salt cellars and ivory spoons like this, specifically this Afro-Portuguese ivory salt cellar was carved in the style of a Benin court ivory, comparable to the famous Benin bronzes and Benin ivory masks.