The Hoyos Mission describes Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Leopold Berchtold's dispatch of his promising 38-year-old private secretary, Alexander Hoyos, to meet with his German counterparts. This secret mission was intended to provide Austro-Hungarian policy-makers with information on the Reich's intentions shortly after the assassination of Franz Ferdinand of Austria, the Imperial and Royal Kronprinz, in Sarajevo. On 5 July 1914, a week after the assassination attempt that claimed the lives of the heir to the throne and his wife, the Austro-Hungarian government sought to officially secure the Reich's support for the actions it wished to take against Serbia in response to the attack. Indeed, the initiatives of the Kingdom of Serbia, victorious in the two Balkan wars, prompted Austro-Hungarian officials to adopt a firm stance in the international crisis opened by the assassination of the Austro-Hungarian heir.

The Bellevue Conference of September 11, 1917, was a council of the German Imperial Crown convened in Berlin, at Bellevue Palace, under the chairmanship of Wilhelm II. This meeting of civilians and military personnel was convened by German Emperor Wilhelm II to determine the Imperial Reich's new war aims policy, in a context marked by the February Revolution and the publication of Pope Benedict XV's note on August 1, 1917; the question of the fate of Belgium, then almost totally occupied by the Reich, quickly focused the participants' attention. Finally, this meeting also had to define the terms of the German response to the papal note, calling on the belligerents to put an end to armed confrontation.

The Berlin Conference of March 31, 1917, was a German governmental meeting designed to define a new direction for the Imperial Reich's war aims in Eastern Europe. Called by the Chancellor of the Reich, this meeting brought together members of the civilian government and officials of the Oberste Heeresleitung to establish the principles that should guide Reich policy in response to the political changes occurring in Russia, which had recently undergone the definitive fall of the monarchy. As a major driving force behind the Central Powers the Reich recognized the need for a clear and objective plan moving forward. For the Reich, the Russian Revolution presented a possibility to impose severe peace terms on Russia and approve extreme initiatives.

The Berlin Conference of August 14, 1917, was a German–Austro-Hungarian diplomatic meeting to define the policy of the Central Powers following the publication of the Papal Note of August 1, 1917. Since April of the previous year, the Reich government members sought to impose unrealistic war aims and to require their Austro-Hungarian counterparts, who were governing a monarchy drained by the prolonged conflict, to share the European conquests of the Central Powers. The objective was to bring the dual monarchy under strict German control.

The Kreuznach Conference on August 9, 1917, was a German government conference that aimed to draft the Reich Government's response to the proposals made on August 1, 1917, by Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Ottokar Czernin for negotiating an honorable way out of the conflict. Additionally, the conference served as the primary meeting between the new Imperial Chancellor, Georg Michaelis, and the two main leaders of the German High Command, Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg. At this meeting, the military tried to impose the war aims they set for the conflict on the members of the civilian government, based on the minutes of the April 23, 1917 conference.

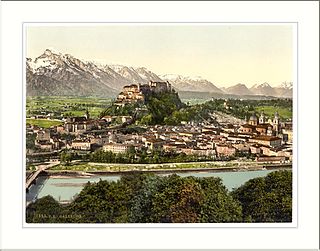

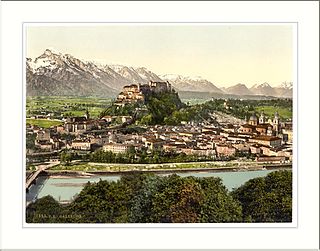

During World War I, a conference took place between the German emperor Wilhelm II and the Austro-Hungarian monarch Charles I in Spa on 12 May 1918. At his meeting, Charles I and his minister Stephan Burián von Rajecz were forced to accept the political and economic subjection of Austria-Hungary to the German Empire in the form of a treaty. Formally concluded on an equal footing between the signatory powers, the agreements reached at Spa in fact endorsed the pre-eminence of Germany and guaranteed its supremacy, while the Austro-Hungarians were forced into a situation of political, economic and military dependence. However, the Spa agreement, which made the dual monarchy subject to an "Austro-German Zollverein", failed to put an end to rivalries in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, or to political disagreements over the end of the conflict or the future of occupied Poland. At the meeting on May 12, German and Austro-Hungarian negotiators agreed to set up technical commissions to put into practice the economic and commercial provisions of the agreement in principle between the emperors. The subsequent Salzburg negotiations, however, fell apart in October with the imminent defeat of Germany and Austria-Hungary.

The Berlin Conference held on December 6 and 7, 1917 was a council of the German Imperial Crown summoned to the Imperial Chancellery by Emperor Wilhelm II to ratify the conditions on which the members of the Quadruple Alliance, or Central Powers would be prepared to accept an armistice with the Council of People's Commissars in power in Russia after the October Revolution.

The Salzburg negotiations were bilateral diplomatic talks designed to precisely and rigorously define the practical details of the economic rapprochement between the dual Austro-Hungarian monarchy and the German Reich. These talks began on July 9, 1918, in Salzburg, an Austrian city close to the German–Austro-Hungarian border, and were intended above all to implement the decisions of principle imposed on Emperor Charles I and his ministers by Emperor Wilhelm II and his advisors at their meeting in Spa on May 12, 1918. Continued throughout the summer, these negotiations were suspended on October 19, 1918, when, without having informed the German negotiators, the Foreign Minister of the Dual Monarchy, Stephan Burián von Rajecz, ordered the Austro-Hungarian delegation to interrupt its participation in the talks, which had been rendered pointless by the development of the situation marked by the inevitability of the military defeat of the Reich and the Dual Monarchy.

The Treaty of Berlin of August 27, 1918 was an agreement signed after several months of negotiations between Bolshevik representatives and the Central Powers, mainly represented by the Germans. This treaty completed and clarified the political and economic clauses of the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, which had been left out of the winter 1917-1918 negotiations. The latter were aimed at ending the war between the Central Powers and Russia and clarifying the extent of Russia's territorial losses, but left unresolved the question of war indemnities due to the Imperial Reich and its allies. Similarly, the nature of the new economic relations between the Central Powers and Russia was not discussed in depth at Brest-Litovsk. Consequently, in accordance with the terms of the peace treaty signed in early 1918, negotiations should regulate future economic relations between the Central Powers and Bolshevik Russia, and lead to the conclusion of an agreement between the Reich and its allies, on the one hand, and Russia, on the other. However, due to the rapid development of the conflict during September and October 1918, the provisions contained in the text of this treaty never came into force. Nevertheless, this agreement laid the foundations for the Treaty of Rapallo between the Reich and Bolshevik Russia, which came into force in 1922.

The Berlin Conference of 26–27 March 1917 was the second governmental meeting between Arthur Zimmermann and Ottokar Czernin, the German and Austro-Hungarian foreign ministers, under the chairmanship of Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg. The meeting was intended to define the war aims of the Germany and the Austria-Hungary, and to prepare for the first official meeting between German Emperor Wilhelm II and the new Emperor-King Charles I. At a time when changes in political personnel were taking place in Austria-Hungary, which was becoming increasingly exhausted by the protracted conflict, this meeting was the first sign of disagreement between the two allies over the conditions for ending the conflict.

The Berlin Conference, held from November 2 to 6, 1917, consisted of a series of meetings between German and Prussian ministers, followed by meetings between German and Austro-Hungarian representatives. The conference was held in Berlin just a few days before the outbreak of the October Revolution. At the same time, the antagonisms between Chancellor Georg Michaelis, supported by State Secretary Richard von Kühlmann, on the one hand, and the military, mainly the Dioscuri, Paul von Hindenburg and Erich Ludendorff, on the other, reached a climax, prompting the military to call for the Chancellor's resignation, formalizing their disagreements over the program for internal reform of the Reich. These differences between political and military leaders also had at stake the definition of a new program of war aims for the Reich, and the concessions the Germans would be prepared to make to their allies, principally the Dual Monarchy, exhausted by more than three years of conflict, but hostile to any excessive reinforcement of German control over Central and Eastern Europe.

The Vienna Conference of August 1, 1917 was a German-Austro-Hungarian governmental conference designed to regulate the sharing of the quadruple European conquests, against a backdrop of growing rivalry and divergence between the Imperial Reich and the Dual Monarchy. Convened at a time when the dual monarchy was sinking into a crisis from which it proved unable to emerge until the autumn of 1918, the Vienna meeting was a further opportunity for German envoys to reaffirm the Reich's weight in the direction of the German-Austrian-Hungarian alliance, on the one hand, and in Europe, on the other.

The Vienna Conference of October 22, 1917 was a German-Austro-Hungarian governmental conference designed to finalize the sharing of the Central Powers European conquests. Meeting in a difficult context for both empires, it resulted in the drafting of a detailed program of German and Austro-Hungarian war aims, referred to by German historian Fritz Fischer as the "Vienna directives", proposing a new program of war aims for the Imperial German Reich, while defining the objectives of the dual monarchy, which was to be further integrated into the German sphere of influence.

The Vienna Conference of March 16, 1917 was the first German-Austro-Hungarian meeting since the outbreak of the February Revolution in Russia. For Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the ministerial meeting was a further opportunity to reaffirm the Reich's war aims in the face of the dual monarchy's new Foreign Minister, Ottokar Czernin. Czernin, the minister of an empire in dire straits, tries to assert the point of view of the dual monarchy, exhausted by two and a half years of conflict, in the face of the Reich, the main driving force behind the quadruplice, and its demands for a compromise peace with the Allies. This decrepitude led Emperor Charles I and his advisors to multiply their initiatives to get out of the conflict, without breaking the alliance with the Reich.

During World War I, the term Dioscuri was used to refer to the OHL duo of Erich Ludendorff and Paul von Hindenburg, after the Dioscuri of Greek mythology. These two soldiers, emboldened by their success against the Russians, exercised full military power in the Reich from 1916. The dismissal of Theobald von Bethmann-Hollweg on 19 July 1917 marked a milestone in the rise of the two soldiers, who gradually imposed their vision of managing the conflict on Kaiser Wilhelm II, forcing him to establish a military dictatorship disguised by the institutions of the Reich.

In 1918, several conferences bringing together the leaders of the Imperial Reich sometimes in the presence of Austro-Hungarian representatives, were convened in Spa in Belgium, the seat of the Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL), the supreme command of the Imperial German Army, since his installation in the city at the end of the winter 1918. Governmental, they were all chaired by the German Emperor Wilhelm II, with the assistance of the Reich Chancellor, and co-chaired by the Emperor-King Charles Iwhen he is present. Also bringing together ministerial officials and high-ranking military personnel, both from the Reich and from the dual monarchy, these conferences were supposed, according to the German imperial government, to define the policy pursued by the Reich and its Quadruple allies, particularly in effecting a division of conquests, by the armies of the Central Powers, into territories to be annexed by the Reich and the dual monarchy, while defining within their respective conquests the zones of German and Austro-Hungarian influence.

The Spa conference of 13–15 August 1918 was a critical meeting between the German and Austro-Hungarian monarchs during World War I. This conference was significant as it marked a shift in the Central Powers' approach, with civil officials beginning to recognize the improbability of a military victory. The German Empire and its allies were increasingly exhausted, and recent offensives had failed on the Marne and the Piave in Italy. This situation, coupled with the massive arrival of American troops reinforcing the Entente forces, led the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian dual monarchy to seriously consider the prospect of a compromise peace.

The Spa conference of September 29, 1918 is the last important conference between the main political and military leaders of the Reich, then engaged in the First World War. Held in the last weeks of the conflict, it is intended to draw the political and military conclusions of the Bulgarian defection. Indeed, after the failures encountered by the central powers in Italy and on the Western Front, the leaders of the Reich can only acknowledge the strategic impasse in which they have found themselves since the month of August 1918. The Allied successes against the Bulgarians, followed by the withdrawal of Bulgaria and the rapid Allied rise towards the Danube, forced those responsible for the Central Powers, mainly Germans, to draw the consequences of their failures. However, kept in ignorance of the reality of the military situation, the members of the Reich government initially remained incredulous in the face of the military's declarations. During the month of September, the latter are urging the government to begin talks with a view to suspending the conflict. The conference constitutes the opportunity to announce this desire for policy change. The conference brought together in Spa, then the headquarters of the Oberste Heeresleitung, the main military leaders of the Reich, the chancellor and his vice-chancellor around Kaiser Wilhelm II. All agreed on the need to request an armistice to limit the demands of the Allies, as well as on political reforms to be implemented to democratize the Reich, which was then to be transformed into a parliamentary monarchy.

The crisis of July 1917 was a political crisis experienced by the German Reich between July 7 and 13, 1917.

The Bingen Conference was a German governmental meeting convened by the new Reich Chancellor Georg Michaelis at the initiative of Wilhelm II to define German policy in the Baltic territories occupied by the German Army since its successes in 1915. This conference was the first opportunity for the new Chancellor, Georg Michaelis, to meet the Dioscuri, Paul von Hindenburg, and Erich Ludendorff. Having come to power after a political crisis caused by differences between his predecessor, Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg, the Reichstag, and the Dioscuri, Georg Michaelis not only had to come to terms with the two actors in his predecessor's downfall but also had to define the war aims of the Reich government under the Oberste Heeresleitung.