Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I. He later became president of Germany from 1925 until his death. During his presidency, he played a key role in the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933 when, under pressure from his advisers, he appointed Adolf Hitler as chancellor of Germany.

The Battle of Verdun was fought from 21 February to 18 December 1916 on the Western Front in France. The battle was the longest of the First World War and took place on the hills north of Verdun-sur-Meuse. The German 5th Army attacked the defences of the Fortified Region of Verdun and those of the French Second Army on the right (east) bank of the Meuse. Using the experience of the Second Battle of Champagne in 1915, the Germans planned to capture the Meuse Heights, an excellent defensive position, with good observation for artillery-fire on Verdun. The Germans hoped that the French would commit their strategic reserve to recapture the position and suffer catastrophic losses at little cost to the German infantry.

The Western Front was one of the main theatres of war during the First World War. Following the outbreak of war in August 1914, the German Army opened the Western Front by invading Luxembourg and Belgium, then gaining military control of important industrial regions in France. The German advance was halted with the Battle of the Marne. Following the Race to the Sea, both sides dug in along a meandering line of fortified trenches, stretching from the North Sea to the Swiss frontier with France, the position of which changed little except during early 1917 and again in 1918.

The Battle of the Somme, also known as the Somme offensive, was a major battle of the First World War fought by the armies of the British Empire and the French Third Republic against the German Empire. It took place between 1 July and 18 November 1916 on both sides of the upper reaches of the river Somme in France. The battle was intended to hasten a victory for the Allies. More than three million men fought in the battle, of whom more than one million were either wounded or killed, making it one of the deadliest battles in all of human history.

Verdun is a large city in the Meuse department in Grand Est, northeastern France. It is an arrondissement of the department.

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg was a German politician who was Chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I and played a key role during its first three years. He was replaced as chancellor in July 1917 due in large part to opposition to his moderate policies by leaders in the military.

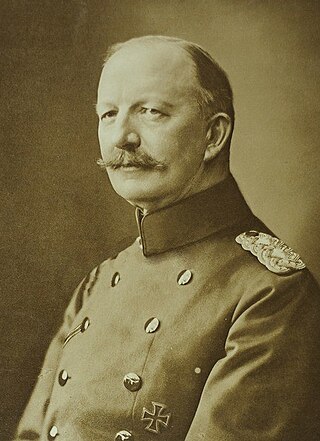

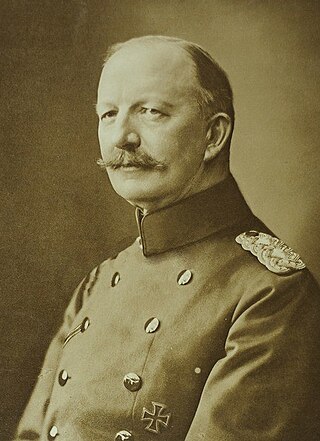

Erich Friedrich Wilhelm Ludendorff was a German general, politician and military theorist. He achieved fame during World War I for his central role in the German victories at Liège and Tannenberg in 1914. Following his appointment as First Quartermaster General of the Imperial German Army's Great General Staff in 1916, he became the chief policymaker in a de facto military dictatorship that dominated Germany for the rest of the war. After Germany's defeat, he contributed significantly to the Nazis' rise to power.

The Oberste Heeresleitung was the highest echelon of command of the army (Heer) of the German Empire. In the latter part of World War I, the Third OHL assumed dictatorial powers and became the de facto political authority in the Empire.

The Supreme Commander of All German Forces in the East, also known by its German abbreviation as Ober Ost, was both a high-ranking position in the armed forces of the German Empire as well as the name given to the occupied territories on the German section of the Eastern Front of World War I, with the exception of Poland. It encompassed the former Russian governorates of Courland, Grodno, Vilna, Kovno and Suwałki. It was governed in succession by Paul von Hindenburg and Prince Leopold of Bavaria, and collapsed by the end of World War I.

Colonel Max Hermann Bauer was a German General Staff officer and artillery expert in the First World War. As a protege of Erich Ludendorff he was placed in charge of the German Army's munition supply by the latter in 1916. In this role he played a leading role in the Hindenburg Programme and the High Command's political machinations. Later Bauer was a military and industrial adviser to the Republic of China under Chiang Kai-shek.

During World War I, the German Empire was one of the Central Powers. It began participation in the conflict after the declaration of war against Serbia by its ally, Austria-Hungary. German forces fought the Allies on both the eastern and western fronts, although German territory itself remained relatively safe from widespread invasion for most of the war, except for a brief period in 1914 when East Prussia was invaded. A tight blockade imposed by the Royal Navy caused severe food shortages in the cities, especially in the winter of 1916–17, known as the Turnip Winter. At the end of the war, Germany's defeat and widespread popular discontent triggered the German Revolution of 1918–1919 which overthrew the monarchy and established the Weimar Republic.

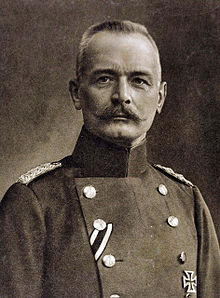

The Hindenburg Programme of August 1916 is the name given to the armaments and economic policy begun in late 1916 by the Third Oberste Heeresleitung, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and General Erich Ludendorff. The two were appointed after the sacking of General Erich von Falkenhayn on 28 August 1916 and intended to double German industrial production, to greatly increase the output of munitions and weapons.

Herrmann Gustav Karl Max von Fabeck was a Prussian military officer and a German General der Infantarie during World War I. He commanded the 13th Corps in the 5th Army and took part in the Race to the Sea on the Western Front and also commanded the new 11th Army on the Eastern Front. Subsequently, he commanded several German armies during the war until his evacuation from the front due to illness in 1916 and died on 16 December. A competent and highly decorated commander, von Fabeck is a recipient of the Pour le Mérite, Prussia's and Germany's highest military honor.

The leaders of the Central Powers of World War I were the political or military figures who commanded or supported the Central Powers.

Eugen von Falkenhayn was a German General of the Cavalry, commanding officer of the XXII Reserve Corps in World War I and Lord Chamberlain of Empress Auguste Viktoria.

Dietrich Gerhard Emil Theodor Tappen was a German World War I general.

The Battle of Kolun was a World War I military engagement fought between Romanian and Central Powers forces. It was part of the wider Battle of Transylvania and resulted in a tactical victory for the Central Powers.

Hermann Friedrich Staabs, von Staabs was a German infantry general in World War I and commanding general of the XXXIX. Reserve Corps.

The 9 January 1917 Crown Council meeting, presided over by German Emperor Wilhelm II, decided on the resumption of unrestricted submarine warfare by the Imperial German Navy during the First World War. The policy had been proposed by the German military in 1916 but was opposed by the civilian government under Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg who feared it would alienate neutral powers, including the United States.

The Bellevue Conference of September 11, 1917, was a council of the German Imperial Crown convened in Berlin, at Bellevue Palace, under the chairmanship of Wilhelm II. This meeting of civilians and military personnel was convened by German Emperor Wilhelm II to determine the Imperial Reich's new war aims policy, in a context marked by the February Revolution and the publication of Pope Benedict XV's note on August 1, 1917; the question of the fate of Belgium, then almost totally occupied by the Reich, quickly focused the participants' attention. Finally, this meeting also had to define the terms of the German response to the papal note, calling on the belligerents to put an end to armed confrontation.