The Balts or Baltic peoples are an ethno-linguistic group of peoples who speak the Baltic languages of the Balto-Slavic branch of the Indo-European languages.

Widewuto was a legendary king of the pagan Prussians who ruled along with his elder brother, the high priest (Kriwe-Kriwajto) Bruteno in the 6th century AD. They are known from writings of 16th-century chroniclers Erasmus Stella, Simon Grunau, and Lucas David. Though the legend lacks historical credibility, it became popular with medieval historians. It is unclear whether the legend was authentically Prussian or was created by Grunau, though Lithuanian researchers tend to support its authenticity.

Sudovian was a West Baltic language of Northeastern Europe. Sudovian was closely related to Old Prussian. It was formerly spoken southwest of the Nemunas river in what is now Lithuania, east of Galindia and in the north of Yotvingia, and by exiles in East Prussia.

The term Galindian is sometimes ascribed to two separate Baltic languages, both of which were peripheral dialects:

Romuva is a neo-pagan movement derived from the traditional mythology of the Lithuanians, attempting to reconstruct the religious rituals of the Lithuanians before their Christianization in 1387. Practitioners of Romuva claim to continue Baltic pagan traditions which survived in folklore, customs and superstition. Romuva is a polytheistic pagan faith which asserts the sanctity of nature and ancestor worship. Practicing the Romuva faith is seen by many adherents as a form of cultural pride, along with celebrating traditional forms of art, retelling Baltic folklore, practicing traditional holidays, playing traditional Baltic music, singing traditional dainos (songs), as well as ecological activism and stewarding sacred places.

Old Prussians, Baltic Prussians or simply Prussians were a tribe among the Baltic peoples that inhabited the region of Prussia, at the south-eastern shore of the Baltic Sea between the Vistula Lagoon to the west and the Curonian Lagoon to the east. The Old Prussians, who spoke an Indo-European language now known as Old Prussian and worshipped pre-Christian deities, lent their name, despite very few commonalities, to the later, predominantly Low German-speaking inhabitants of the region.

Yotvingians were a Western Baltic people who were closely tied to the Old Prussians. The linguist Petras Būtėnas asserts that they were closest to the Lithuanians. The Yotvingians contributed to the formation of the Lithuanian state.

Lithuanian mythology is the mythology of Lithuanian polytheism, the religion of pre-Christian Lithuanians. Like other Indo-Europeans, ancient Lithuanians maintained a polytheistic mythology and religious structure. In pre-Christian Lithuania, mythology was a part of polytheistic religion; after Christianisation mythology survived mostly in folklore, customs and festive rituals. Lithuanian mythology is very close to the mythology of other Baltic nations – Prussians, Latvians, and is considered a part of Baltic mythology.

Žemyna is the goddess of the earth in Lithuanian religion. She is usually regarded as mother goddess and one of the chief Lithuanian gods similar to Latvian Zemes māte. Žemyna personifies the fertile earth and nourishes all life on earth, human, plant, and animal. All that is born of earth will return to earth, thus her cult is also related to death. As the cult diminished after baptism of Lithuania, Žemyna's image and functions became influenced by the cult of Virgin Mary.

Potrimpo was a god of seas, earth, grain, and crops in the pagan Baltic, and Prussian mythology. He was one of the three main gods worshiped by the Old Prussians. Most of what is known about this god is derived from unreliable 16th-century sources.

The Nadruvians were a now-extinct Prussian tribe. They lived in Nadruvia, a large territory in northernmost Prussia. They bordered the Skalvians on the Neman (Nemunas) River just to the north, the Sudovians to the east, and other Prussian tribes to the south and west. Most information about the clan is provided in a chronicle by Peter von Dusburg.

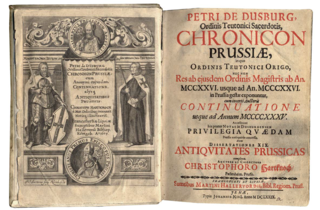

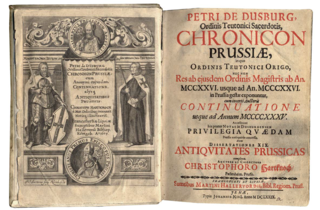

Chronicon terræ Prussiæ is a chronicle of the Teutonic Knights, by Peter of Dusburg, finished in 1326. The manuscript is the first major chronicle of the Teutonic Order in Prussia and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, completed some 100 years after the conquest of the crusaders into the Baltic region. It is a major source for information on the Order's battles with Old Prussians and Lithuanians.

Baltic neopaganism is a category of autochthonous religious movements which have revitalised within the Baltic people. These movements trace their origins back to the 19th century and they were suppressed under the Soviet Union; after its fall they have witnessed a blossoming alongside the national and cultural identity reawakening of the Baltic peoples, both in their homelands and among expatriate Baltic communities, with close ties to conservation movements. One of the first ideologues of the revival was the Prussian Lithuanian poet and philosopher Vydūnas.

Gintaras Beresnevičius was a Lithuanian historian of religions specializing in Baltic mythology. He together with Norbertas Vėlius is considered to be the best specialist in Lithuanian mythology.

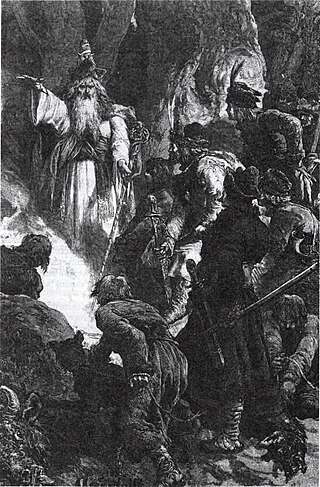

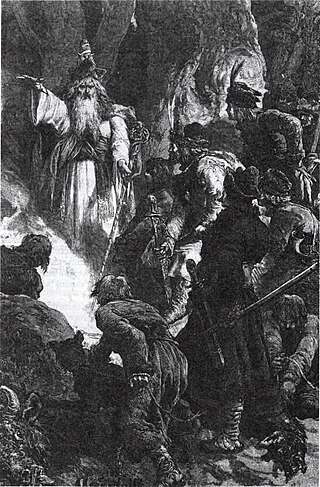

Romuva or Romowe was an alleged pagan worship place in the western part of Sambia, one of the regions of pagan Prussia. In contemporary sources the temple is mentioned only once, by Peter von Dusburg in 1326. According to his account, Kriwe-Kriwajto, the chief priest or "pagan pope", lived at Romuva and ruled over the religion of all the Balts. According to Simon Grunau, the temple was central to Prussian mythology. Even though there are considerable doubts whether such a place actually existed, the Lithuanian neo-pagan movement Romuva borrowed its name from the temple.

Bārta, also named Bartuva, is a river in western Lithuania and Latvia. It originates in the Plungė district, 3 km to north of Lake Plateliai. The Bārta flows in a northwesterly direction, passing through the Skuodas district and the city of Skuodas, before entering Latvia. The Bārta flows into Liepāja lake, which is connected with the Baltic Sea. In its upper courses the valley formed by the Bārta is deep and narrow, while in its lower courses it is much wider.

Simon Grunau was the author of Preussische Chronik, the first comprehensive history of Prussia. The only personal information available is what he wrote himself in his work: that he was a Dominican priest from Tolkemit (Tolkmicko) near Frauenburg (Frombork) just north of Elbing (Elbląg) in the Monastic State of the Teutonic Order. He preached in Danzig (Gdańsk) and claimed to have met Pope Leo X and Polish King Sigismund I the Old. The chronicle was written in the German language sometime between 1517 and 1529. Its 24 chapters deal with Prussian landscape, agriculture, inhabitants, their customs, and history from earliest times to up to 1525 when the Protestant Duchy of Prussia was created. It also contains a short vocabulary of the Prussian language, one of the very few written artifacts of this extinct language. While often biased and based on dubious sources, this work became very popular and is the principal source of information on Prussian mythology. The chronicle circulated as a frequently copied manuscript and was first published in 1876. Modern historians often dismiss the Preussische Chronik as a work of fiction.

Kūlgrinda is a folk music group from Vilnius, Lithuania, established in 1989 by Inija and Jonas Trinkūnas. The group is connected to the Lithuanian neopagan movement Romuva and often performs as a part of the movement's ceremonies.

The Prussian mythology was a polytheistic religion of the Old Prussians, indigenous peoples of Prussia before the Prussian Crusade waged by the Teutonic Knights. It was closely related to other Baltic faiths, the Lithuanian and Latvian mythologies. Its myths and legends did not survive as Prussians became Germanized and their culture went extinct in the early 18th century. Fragmentary information on gods and rituals can be found in various medieval chronicles, but most of them are unreliable. No sources document pagan religion before the forced Christianization in the 13th century. Most of what is known about Prussian religion is obtained from dubious 16th-century sources.

Lizdeika was a semi-legendary pagan priest (kriwe) in the 14th-century Grand Duchy of Lithuania. He is associated with the legend of founding of Vilnius recorded in the 16th-century Lithuanian Chronicles. The legend became popular durign the 19th-century romantic nationalism.