The Krupp family, a prominent 400-year-old German dynasty from Essen, is notable for its production of steel, artillery, ammunition and other armaments. The family business, known as Friedrich Krupp AG, was the largest company in Europe at the beginning of the 20th century, and was the premier weapons manufacturer for Germany in both world wars. Starting from the Thirty Years' War until the end of the Second World War, it produced battleships, U-boats, tanks, howitzers, guns, utilities, and hundreds of other commodities.

The Nuremberg trials were held by the Allies against representatives of the defeated Nazi Germany, for plotting and carrying out invasions of other countries, and other crimes, in World War II.

Interessengemeinschaft Farbenindustrie AG, commonly known as IG Farben, was a German chemical and pharmaceutical conglomerate. Formed in 1925 from a merger of six chemical companies—BASF, Bayer, Hoechst, Agfa, Chemische Fabrik Griesheim-Elektron, and Chemische Fabrik vorm. Weiler Ter Meer—it was seized by the Allies after World War II and divided back into its constituent companies.

Gustav Georg Friedrich Maria Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was a German foreign service official who became chairman of the board of Friedrich Krupp AG, a heavy industry conglomerate, after his marriage to Bertha Krupp, who had inherited the company. He and his son Alfried would lead the company through two world wars, producing almost everything for the German war machine from U-boats, battleships, howitzers, trains, railway guns, machine guns, cars, tanks, and much more. Krupp produced the Tiger I tank, Big Bertha and the Paris Gun, among other inventions, under Gustav. Following World War II, plans to prosecute him as a war criminal at the 1945 Nuremberg Trials were dropped because by then he was bedridden, senile, and considered medically unfit for trial. The charges against him were held in abeyance in case he were found fit for trial.

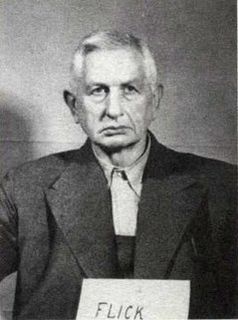

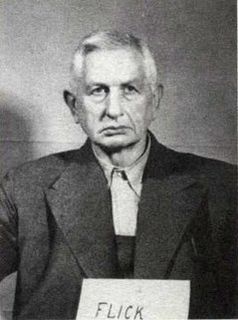

Friedrich Flick was a German industrialist and convicted Nazi war criminal. After the Second World War, he reconstituted his businesses, becoming the richest person in West Germany, and one of the richest people in the world, at the time of his death in 1972.

The Judges' Trial was the third of the 12 trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany in Nuremberg after the end of World War II. These twelve trials were all held before U.S. military courts, not before the International Military Tribunal, but took place in the same rooms at the Palace of Justice. The twelve U.S. trials are collectively known as the "Subsequent Nuremberg Trials" or, more formally, as the "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals" (NMT).

The Milch Trial was the second of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany in Nuremberg after the end of World War II. These twelve trials were all held before U.S. military courts, not before the International Military Tribunal, but took place in the same rooms at the Palace of Justice. The twelve U.S. trials are collectively known as the "Subsequent Nuremberg Trials" or, more formally, as the "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals" (NMT).

The United States of America vs. Friedrich Flick, et al. or Flick Trial was the fifth of twelve Nazi war crimes trials held by United States authorities in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) after World War II. It was the first of three trials of leading industrialists of Nazi Germany; the two others were the IG Farben Trial and the Krupp Trial.

The United States of America vs. Carl Krauch, et al., also known as the IG Farben Trial, was the sixth of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany (Nuremberg) after the end of World War II. IG Farben was the private German chemicals company allied with the Nazis that manufactured the Zyklon B gas used to commit genocide against millions of European Jews in the Holocaust.

The Ministries Trial was the eleventh of the twelve trials for war crimes the U.S. authorities held in their occupation zone in Germany in Nuremberg after the end of World War II. These twelve trials were all held before U.S. military courts, not before the International Military Tribunal, but took place in the same rooms at the Palace of Justice. The twelve U.S. trials are collectively known as the "Subsequent Nuremberg Trials" or, more formally, as the "Trials of War Criminals before the Nuremberg Military Tribunals" (NMT).

Alfried Felix Alwyn Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, often referred to as Alfried Krupp, was a German industrialist, a competitor in Olympic yacht races, and a member of the Krupp family, which has been prominent in German industry since the early 19th century. He was convicted after World War II of crimes against humanity for the genocidal manner in which he operated his factories and sentenced to twelve years in prison subsequently commuted to three years with time served in 1951.

Bertha Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach was a member of the Krupp family, Germany's leading industrial dynasty of the 19th and 20th centuries. As the elder child and heir of Friedrich Alfred Krupp she was the sole proprietor of the Krupp industrial empire from 1902 to 1943, although her husband, Gustav Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, ran the company in her name. In 1943 ownership of the company was transferred to her son Alfried.

A war crimes trial is the trial of persons charged with criminal violation of the laws and customs of war and related principles of international law committed during armed conflict.

Fritz ter Meer was a German chemist, Bayer board chairman, Nazi Party member and war criminal.

The Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation is a major German philanthropic foundation, created by and named in honor of Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach, former owner and head of the Krupp company and a convicted war criminal.

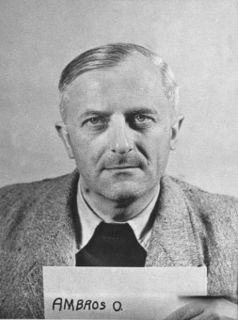

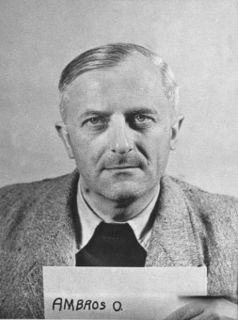

Otto Ambros was a German chemist and Nazi war criminal. He is known for his wartime work on synthetic rubber and nerve agents. After the war he was tried at Nuremberg and convicted of crimes against humanity for his use of slave labor from the Auschwitz III–Monowitz concentration camp.

Wehrwirtschaftsführer (WeWiFü) were, during the time of Nazi Germany (1933–1945), executives of companies or big factories called rüstungswichtiger Betrieb. Wehrwirtschaftsführer were appointed, starting 1935, by the Wehrwirtschafts und Rüstungsamt being a part of the Oberkommando der Wehrmacht, that was pushing the build-up of arms for the Wehrmacht. The purpose of the appointment was to bind them to the Wehrmacht and to give them a quasi-military status.

David W. Peck was an American jurist. From 1947 to 1957, he was Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department in New York, and in that time took a leading role in the reform of judiciary of that state. In 1950, in Germany, Peck led the Advisory Board on Clemency on recommendations for clemency for convicted war and Nazi criminals.

The Alfried Krupp Institute for Advanced Study in Greifswald is an institute for advanced study named after Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach. On 20 June 2000, this institute was founded by the Alfried Krupp von Bohlen und Halbach Foundation, the German Land of Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and the University of Greifswald. These three founders co-established and contributed to the Stiftung Alfried Krupp Kolleg Greifswald, which was entrusted with the task of establishing this Wissenschaftskolleg. The Krupp Foundation contributed the plot of land and the building on it, valued at €15.3m, while Mecklenburg-Vorpommern and the University of Greifswald contributed the operational funding that initially amounted to €4.1m.

Private sector participation in Nazi crimes was extensive and included widespread use of forced labor in Nazi Germany and German-occupied Europe, confiscation of property from Jews and other victims by banks and insurance companies, and the transportation of people to Nazi concentration camps and extermination camps by rail. After the war, companies sought to downplay their participation in crimes and claimed that they were also victims of Nazi totalitarianism. However, the role of the private sector in Nazi Germany has been described as an example of state-corporate crime.