Hadad, Haddad, Adad, or Iškur (Sumerian) was the storm and rain god in the Canaanite and ancient Mesopotamian religions. He was attested in Ebla as "Hadda" in c. 2500 BCE. From the Levant, Hadad was introduced to Mesopotamia by the Amorites, where he became known as the Akkadian (Assyrian-Babylonian) god Adad. Adad and Iškur are usually written with the logogram 𒀭𒅎dIM—the same symbol used for the Hurrian god Teshub. Hadad was also called Pidar, Rapiu, Baal-Zephon, or often simply Baʿal (Lord), but this title was also used for other gods. The bull was the symbolic animal of Hadad. He appeared bearded, often holding a club and thunderbolt and wearing a bull-horned headdress. Hadad was equated with the Greek god Zeus, the Roman god Jupiter, as well as the Babylonian Bel.

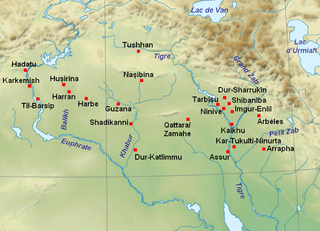

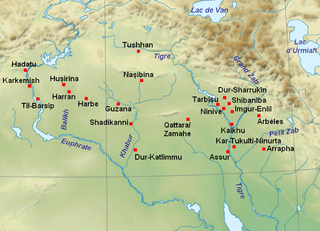

Aram was a historical region mentioned in early cuneiforms and in the Bible, populated by Arameans. The area did not develop into a larger empire but consisted of a number of small states in present-day Syria. Some of the states are mentioned in the Old Testament, Damascus being the most outstanding one, which came to encompass most of Syria. Furthermore, Aram-Damascus is commonly referred to as simply Aram in the Old Testament.

The Tel Dan Stele is a fragmentary stele containing an Aramaic inscription which dates to the 9th century BCE. It is the earliest known extra-biblical archaeological reference to the house of David.

A nefesh is a Semitic monument placed near a grave so as to be seen from afar.

Zincirli Höyük is an archaeological site located in the Anti-Taurus Mountains of modern Turkey's Gaziantep Province. During its time under the control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire it was called, by them, Sam'al. It was founded at least as far back as the Early Bronze Age and thrived between 3000 and 2000 BC, and on the highest part of the upper mound was found a walled citadel of the Middle Bronze Age. New excavations revealed a monumental complex in the Middle Bronze Age II, and another structure that was destroyed in the mid to late 17th century BC, maybe by Hititte king Hattusili I. This event was recently radiocarbon-dated to sometime between 1632 and 1610 BC, during the late Middle Bronze Age II. The site was thought to have been abandoned during the Hittite and Mitanni periods, but excavations in 2021 season showed evidence of occupation during the Late Bronze Age in Hittite times. It flourished again in the Iron Age, initially under Luwian-speaking Neo-Hittites, and by 920 B.C. had become a kingdom. In the 9th and 8th century BC it came under control of the Neo-Assyrian Empire and by the 7th century BC had become a directly ruled Assyrian province.

The states called Neo-Hittite, Syro-Hittite, or Luwian-Aramean were Luwian and Aramean regional polities of the Iron Age, situated in southeastern parts of modern Turkey and northwestern parts of modern Syria, known in ancient times as lands of Hatti and Aram. They arose following the collapse of the Hittite New Kingdom in the 12th century BCE, and lasted until they were subdued by the Assyrian Empire in the 8th century BCE. They are grouped together by scholars, on the basis of several cultural criteria, that are recognized as similar and mutually shared between both societies, northern (Luwian) and southern (Aramaean). Cultural exchange between those societies is seen as a specific regional phenomenon, particularly in light of significant linguistic distinctions between the two main regional languages, with Luwian belonging to the Anatolian group of Indo-European languages and Aramaic belonging to the Northwest Semitic group of Semitic languages. Several questions related to the regional grouping of Luwian and Aramaean states are viewed differently among scholars, including some views that are critical towards such grouping in general.

Til Barsip or Til Barsib is an ancient site situated in Aleppo Governorate, Syria by the Euphrates river about 20 kilometers south of ancient Carchemish.

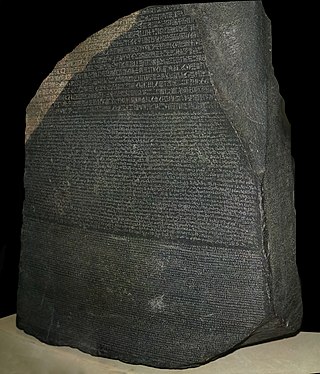

In epigraphy, a multilingual inscription is an inscription that includes the same text in two or more languages. A bilingual is an inscription that includes the same text in two languages. Multilingual inscriptions are important for the decipherment of ancient writing systems, and for the study of ancient languages with small or repetitive corpora.

The Sfire or Sefire steles are three 8th-century BCE basalt stelae containing Aramaic inscriptions discovered near Al-Safirah ("Sfire") near Aleppo, Syria. The Sefire treaty inscriptions are the three inscriptions on the steles; they are known as KAI 222-224. A fourth stele, possibly from Sfire, is known as KAI 227.

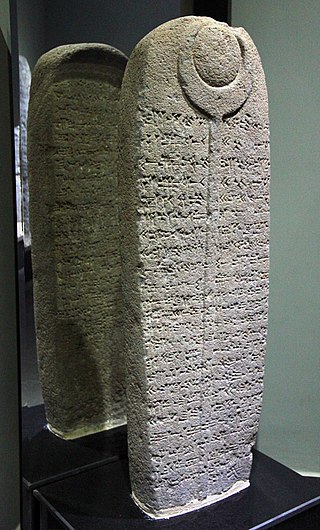

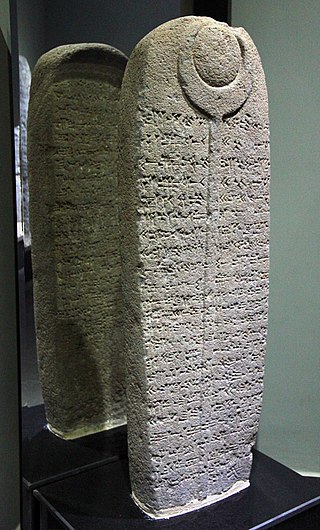

Kuttamuwa was an 8th-century BC royal official from Aramean city Sam'al named on the Kuttamuwa stele, that was to be erected upon his death. The inscription in Aramaic requested that his mourners commemorate his life and his afterlife with feasts "for my soul that is in this stele". It is one of the earliest references to a soul as a separate entity from the body. The 800-pound basalt stele is three feet tall and two feet wide. It was uncovered in the third season of excavations by the Neubauer Expedition of the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois. The official publication was by Dennis Pardee, “A New Aramaic Inscription from Zincirli.” Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research, no. 356, 2009, pp. 51–71

The Kilamuwa Stele is a 9th-century BC stele of King Kilamuwa, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari. He claims to have succeeded where his ancestors had failed, in providing for his kingdom. The inscription is known as KAI 24.

The Pazarcık Stele is an Assyrian monument which functioned as a boundary stone erected by the Assyrian king Adad-nirari III in 805 BC to demarcate the border between the kingdoms of Kummuh and Gurgum. The reverse and obverse of the stele have been inscribed in the Akkadian language in different times.

Samalian was a Semitic language spoken and first attested in Samʼal.

The Hadad-yith'i bilingual inscription, also known as the Tell el Fakhariya Bilingual Inscription is a bilingual inscription found on a Neo-Assyrian statue of Adad-it'i/Hadd-yith'i, the king of Guzana and Sikan, which was discovered at Tell Fekheriye in Syria in the late 1970s. The inscriptions are in the Assyrian dialect of Akkadian and Aramaic, the earliest Aramaic inscription. The statue, a standing figure wearing a tunic, is made of basalt and is 2 meters tall including the base. The two inscriptions are on the skirt of the tunic, with the Akkadian inscription on the front and the Aramaic inscription on the back. The text is most likely based on an Aramaic prototype. It is the earliest known Aramaic inscription, and is known as KAI 309.

The Melqart stele, also known as the Ben-Hadad or Bir-Hadad stele is an Aramaic stele which was created during the 9th century BCE and was discovered in 1939 in Roman ruins in Bureij Syria. The Old Aramaic inscription is known as KAI 201; its five lines reads:

“The stele which Bar-Had-

-ad, son of [...]

king of Aram, erected to his Lord Melqar-

-t, to whom he made a vow and who heard his voi-

-ce.”

The Canaanite and Aramaic inscriptions, also known as Northwest Semitic inscriptions, are the primary extra-Biblical source for understanding of the society and history of the ancient Phoenicians, Hebrews and Arameans. Semitic inscriptions may occur on stone slabs, pottery ostraca, ornaments, and range from simple names to full texts. The older inscriptions form a Canaanite–Aramaic dialect continuum, exemplified by writings which scholars have struggled to fit into either category, such as the Stele of Zakkur and the Deir Alla Inscription.

The Daskyleion steles are three marble steles discovered in 1958 in Dascylium, in northwest Turkey.

The Hadad Statue is an 8th-century BC stele of King Panamuwa I, from the Kingdom of Bit-Gabbari in Sam'al. It is currently occupies a prominent position in the Vorderasiatisches Museum Berlin.

The Kilamuwa scepter or Kilamuwa sheath is an 9th-century BCE small gold object inscribed in Phoenician or Aramaic, which was found during the excavations of Zincirli in 1943. It was found in burned debris in a corridor at the front of the "Building of Kilamuwa".