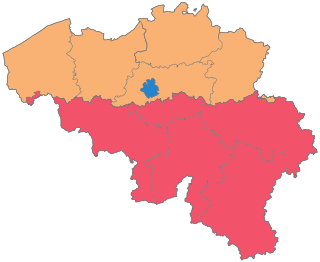

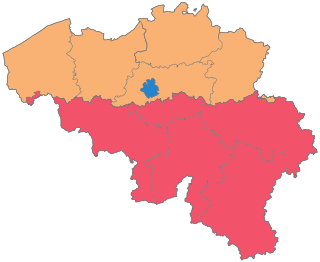

Belgium is a federal state comprising three communities and three regions that are based on four language areas. For each of these subdivision types, the subdivisions together make up the entire country; in other words, the types overlap.

The Kingdom of Belgium is divided into three regions. Two of these regions, Flanders and Wallonia, are each subdivided into five provinces. The third region, Brussels, does not belong to any province and nor is it subdivided into provinces. Instead, it has amalgamated both regional and provincial functions into a single "Capital Region" administration.

Sint-Genesius-Rode is a municipality located in Flanders, one of three regions of Belgium, in the province of Flemish Brabant. The municipality comprises the town of Sint-Genesius-Rode only, and lies between Brussels and Waterloo in Wallonia. On January 1, 2008, the town had a total population of 18,021. The total area is 22.77 square kilometres (8.79 sq mi), which gives a population density of 791 per square kilometre (2,050/sq mi).

Vooruit is a Flemish social democratic political party in Belgium. The party was known as the Flemish Socialist Party until 21 March 2021, when its current name was adopted.

The Flemish Movement is an umbrella term which encompasses various political groups in the Belgian region of Flanders and, less commonly, in French Flanders. Ideologically, it encompasses groups which have sought to promote Flemish culture and the Dutch language as well as those seeking greater political autonomy for Flanders within Belgium. It also encompassed nationalists who seek the secession of Flanders from Belgium, either through outright independence or unification with the Netherlands.

The Flemish Region, usually simply referred to as Flanders, is one of the three regions of Belgium—alongside the Walloon Region and the Brussels-Capital Region. Covering the northern portion of the country, the Flemish Region is primarily Dutch-speaking. With an area of 13,522 km2 (5,221 sq mi), it accounts for only 45% of Belgium's territory, but 57% of its population. It is one of the most densely populated regions of Europe with around 490/km2 (1,300/sq mi).

In Belgium, there are 27 municipalities with language facilities, which must offer linguistic services to residents in Dutch, French, or German in addition to their single official languages. All other municipalities – with the exception of those in the bilingual Brussels region – are monolingual and only offer services in their official languages, either Dutch or French.

The Flemish Community is one of the three institutional communities of Belgium, established by the Belgian constitution and having legal responsibilities only within the precise geographical boundaries of the Dutch-language area and of the bilingual area of Brussels-Capital. Unlike in the French Community of Belgium, the competences of the Flemish Community have been unified with those of the Flemish Region and are exercised by one directly elected Flemish Parliament based in Brussels.

Jean-Marie Louis Dedecker is a Belgian politician.

The area within Belgium known as Brussels-Halle-Vilvoorde encompasses the bilingual—French and Dutch—Brussels-Capital Region, which coincides with the arrondissement of Brussels-Capital and the surrounding Dutch-speaking area of Halle-Vilvoorde, which in turn coincides with the arrondissement of Halle-Vilvoorde. Halle-Vilvoorde contains several municipalities with language facilities, i.e. municipalities where French-speaking people form a considerable part of the population and therefore have special language rights. This area forms the judicial arrondissement of Brussels, which is the location of a tribunal of first instance, enterprise tribunal and a labour tribunal. It was reformed in July 2012, as part of the sixth Belgian state reform.

The Dutch-speaking electoral college is one of three constituencies of the European Parliament in Belgium. It currently elects 12 MEPs using the D'Hondt method of party-list proportional representation. Previously it elected 13 MEPS, until the 2013 accession of Croatia. Before that, it elected 14 MEPs, until the 2007 accession of Bulgaria and Romania.

Federal elections were held in Belgium on 10 June 2007. Voters went to the polls in order to elect new members for the Chamber of Representatives and Senate.

Jan Coucke and Pieter Goethals were two Flemings who were sentenced to death for murder in 1860 at a time Belgium was legally only French-speaking, though the majority of the citizens spoke Dutch, and only the official language was acknowledged by the Courts of Justice. They became an example as well as an exponent of how the French-speaking bourgeoisie treated their Flemish fellow-citizens, of whom the language – if not its speakers – was considered inferior by the elite. Later on, the real perpetrators confessed to the murder, which in 1873 led to a debate in parliament that ended in the Coremans Act, one of the first laws to recognize Dutch as an official language in Belgium, allowing the Flemish to use their own language at Flemish courts, though not yet in Brussels.

The partition of Belgium is a hypothetical situation, which has been discussed by both Belgian and international media, envisioning a split of Belgium along linguistic divisions, with the Flemish Community (Flanders) and the French-speaking Community (Wallonia) becoming independent states. Alternatively, it is hypothesized that Flanders could join the Netherlands and Wallonia could join France or Luxembourg.

The 2009 European Parliament election in Belgium was on Sunday 7 June 2009 and was the election of the delegation from Belgium to the European Parliament. The elections were on the same day as regional elections to the Flemish Parliament, Walloon Parliament, Brussels Parliament and the Parliament of the German-speaking Community.

The Francization of Brussels refers to the evolution, over the past two centuries, of this historically Dutch-speaking city into one where French has become the majority language and lingua franca. The main cause of this transition was the rapid, yet non-compulsory assimilation of the Flemish population, amplified by immigration from France and Wallonia.

Following the Belgian general election held on 13 June 2010, a process of cabinet formation started in Belgium. The election produced a very fragmented political landscape, with 11 parties elected to the Chamber of Representatives, none of which won more than 20% of the seats. The Flemish-Nationalist New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), the largest party in Flanders and the country as a whole, controlled 27 of 150 seats in the lower chamber. The Francophone Socialist Party (PS), the largest in Wallonia, controlled 26 seats. Cabinet negotiations continued for a long time. On 1 June 2011, Belgium matched the record for time taken to form a new democratic government after an election, at 353 days, held until then by Cambodia in 2003–2004. On 11 October 2011, the final agreement for institutional reform was presented to the media. A government coalition was named on 5 December 2011 and sworn in after a total of 541 days of negotiations and formation on 6 December 2011, and 589 days without an elected government with Elio Di Rupo named Prime Minister of the Di Rupo I Government.

The Di Rupo Government was the federal cabinet of Belgium sworn in on 6 December 2011, after a record-breaking 541 days of negotiations following the June 2010 elections. The government included social democrats (sp.a/PS), Christian democrats (CD&V/cdH) and liberals, respectively of the Dutch and French language groups. The government notably excluded the New Flemish Alliance (N-VA), the Flemish nationalist party which achieved a plurality and became the largest party. Its absence, together with the unwillingness of Open Vld to enter into an eight-party coalition that included the green parties, caused the government coalition to lack a majority in the Dutch language group. It was the first time that the Belgian prime minister had been openly gay, as Di Rupo became the world's first male openly gay head of government. Elio Di Rupo also became the first native French-speaking prime minister since 1979 and the first prime minister from Wallonia since 1974 and first socialist prime minister since 1974.

Federal elections were held in Belgium on 26 May 2019, alongside the country's European and regional elections. All 150 members of the Chamber of Representatives were elected from eleven multi-member constituencies.

The 2019 Belgian regional elections took place on Sunday 26 May, the same day as the 2019 European Parliament election as well as the Belgian federal election.