Cause

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

| Laryngeal cleft |

|---|

A laryngeal cleft or laryngotracheoesophageal cleft is a rare congenital abnormality in the posterior laryngo-tracheal wall. [1] It occurs in approximately 1 in 10,000 to 20,000 births. [2] It means there is a communication between the oesophagus and the trachea, which allows food or fluid to pass into the airway. [3]

Twenty to 27% of individuals with a laryngeal cleft also have a tracheoesophageal fistula and approximately 6% of individuals with a fistula also have a cleft. [4] Other congenital anomalies commonly associated with laryngeal cleft are gastro-oesophageal reflux, tracheobronchomalacia, congenital heart defect, dextrocardia and situs inversus. [5] Laryngeal cleft can also be a component of other genetic syndromes, including Pallister–Hall syndrome and G syndrome (Opitz-Frias syndrome). [4]

| | This section is empty. You can help by adding to it. (December 2024) |

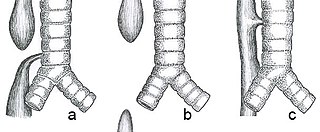

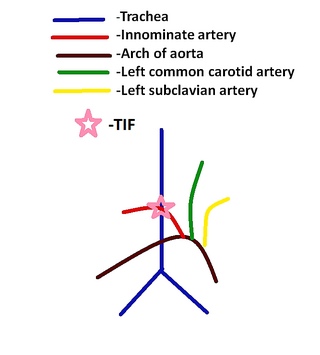

Laryngeal cleft is usually diagnosed in an infant after they develop problems with feeding, such as coughing, cyanosis (blue lips) and failing to gain weight over time. [3] Pulmonary infections are also common. [4] The longer the cleft, the more severe are the symptoms. Laryngeal cleft is suspected after a video swallow study (VSS) shows material flowing into the airway rather than the esophagus, and diagnosis is confirmed through endoscopic examination, specifically microlaryngoscopy and bronchoscopy. [4] [5] If a laryngeal cleft is not seen on flexible nasopharyngoscopy, that does not mean that there is not one there. Laryngeal clefts are classified into four types according to Benjamin and Inglis. Type I clefts extend down to the vocal cords; Type II clefts extend below the vocal cords and into the cricoid cartilage; Type III clefts extend into the cervical trachea and Type IV clefts extend into the thoracic trachea. [5] Subclassification of type IV clefts into Type IVA (extension to 5 mm below the innominate artery) and Type IV B (extension greater than 5 mm below the innominate artery) may help with preoperative selection of those who can be repaired via transtracheal approach (Type IV A) versus a cricotracheal separation approach (type IV B). [6] [7]

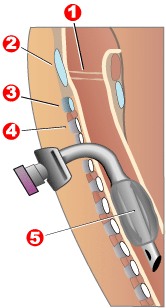

Treatment of a laryngeal cleft depends on the length and resulting severity of symptoms. A shallow cleft (Type I) may not require surgical intervention. [5] Symptoms may be able to be managed by thickening the infant's feeds. [5] If symptomatic, Type I clefts can be sutured closed or injected with filler as a temporary fix to determine if obliterating the cleft is beneficial and whether or not a more formal closure is required at a later date. [8] Slightly longer clefts (Type II and short Type III) can be repaired endoscopically. Short type IV clefts extending to within 5 mm below the innominate artery can be repaired through the neck by splitting the trachea vertically in the midline and suturing the back layers of the esophagus and trachea closed. [6] A long, tapered piece of rib graft can be placed between the esophageal and tracheal layers to make them rigid so the patient will not require a tracheotomy after the surgery and to decrease chances of fistula postoperatively. [6] Long Type IV clefts extending further than 5 mm below the innominate artery cannot be reached with a vertical incision in the trachea, and therefore are best repaired through cricotracheal resection. [7] This involves separating the trachea from the cricoid cartilage, leaving the patient intubated through the trachea, suturing each of the esophagus and the back wall of the trachea closed independently, and then reattaching the trachea to the cricoid cartilage. [7] This prevents the need for pulmonary bypass or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation.[ citation needed ]

The larynx, commonly called the voice box, is an organ in the top of the neck involved in breathing, producing sound and protecting the trachea against food aspiration. The opening of larynx into pharynx known as the laryngeal inlet is about 4–5 centimeters in diameter. The larynx houses the vocal cords, and manipulates pitch and volume, which is essential for phonation. It is situated just below where the tract of the pharynx splits into the trachea and the esophagus. The word 'larynx' comes from the Ancient Greek word lárunx ʻlarynx, gullet, throatʼ.

The trachea, also known as the windpipe, is a cartilaginous tube that connects the larynx to the bronchi of the lungs, allowing the passage of air, and so is present in almost all animals lungs. The trachea extends from the larynx and branches into the two primary bronchi. At the top of the trachea, the cricoid cartilage attaches it to the larynx. The trachea is formed by a number of horseshoe-shaped rings, joined together vertically by overlying ligaments, and by the trachealis muscle at their ends. The epiglottis closes the opening to the larynx during swallowing.

Tracheal intubation, usually simply referred to as intubation, is the placement of a flexible plastic tube into the trachea (windpipe) to maintain an open airway or to serve as a conduit through which to administer certain drugs. It is frequently performed in critically injured, ill, or anesthetized patients to facilitate ventilation of the lungs, including mechanical ventilation, and to prevent the possibility of asphyxiation or airway obstruction.

Esophageal atresia is a congenital medical condition that affects the alimentary tract. It causes the esophagus to end in a blind-ended pouch rather than connecting normally to the stomach. It comprises a variety of congenital anatomic defects that are caused by an abnormal embryological development of the esophagus. It is characterized anatomically by a congenital obstruction of the esophagus with interruption of the continuity of the esophageal wall.

The brachiocephalic artery, brachiocephalic trunk, or innominate artery is an artery of the mediastinum that supplies blood to the right arm, head, and neck.

Tracheotomy, or tracheostomy, is a surgical airway management procedure which consists of making an incision (cut) on the anterior aspect (front) of the neck and opening a direct airway through an incision in the trachea (windpipe). The resulting stoma (hole) can serve independently as an airway or as a site for a tracheal tube or tracheostomy tube to be inserted; this tube allows a person to breathe without the use of the nose or mouth.

A tracheal tube is a catheter that is inserted into the trachea for the primary purpose of establishing and maintaining a patent airway and to ensure the adequate exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide.

A tracheoesophageal fistula is an abnormal connection (fistula) between the esophagus and the trachea. TEF is a common congenital abnormality, but when occurring late in life is usually the sequela of surgical procedures such as a laryngectomy.

The recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) is a branch of the vagus nerve that supplies all the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, with the exception of the cricothyroid muscles. There are two recurrent laryngeal nerves, right and left. The right and left nerves are not symmetrical, with the left nerve looping under the aortic arch, and the right nerve looping under the right subclavian artery, then traveling upwards. They both travel alongside the trachea. Additionally, the nerves are among the few nerves that follow a recurrent course, moving in the opposite direction to the nerve they branch from, a fact from which they gain their name.

The cricoid cartilage, or simply cricoid or cricoid ring, is the only complete ring of cartilage around the trachea. It forms the back part of the voice box and functions as an attachment site for muscles, cartilages, and ligaments involved in opening and closing the airway and in producing speech.

In anatomy, the left and right common carotid arteries (carotids) are arteries that supply the head and neck with oxygenated blood; they divide in the neck to form the external and internal carotid arteries.

The lung bud sometimes referred to as the respiratory bud forms from the respiratory diverticulum, an embryological endodermal structure that develops into the respiratory tract organs such as the larynx, trachea, bronchi and lungs. It arises from part of the laryngotracheal tube.

A branchial cleft cyst or simply branchial cyst is a cyst as a swelling in the upper part of neck anterior to sternocleidomastoid. It can, but does not necessarily, have an opening to the skin surface, called a fistula. The cause is usually a developmental abnormality arising in the early prenatal period, typically failure of obliteration of the second, third, and fourth branchial cleft, i.e. failure of fusion of the second branchial arches and epicardial ridge in lower part of the neck. Branchial cleft cysts account for almost 20% of neck masses in children. Less commonly, the cysts can develop from the first, third, or fourth clefts, and their location and the location of associated fistulas differs accordingly.

Tracheobronchial injury is damage to the tracheobronchial tree. It can result from blunt or penetrating trauma to the neck or chest, inhalation of harmful fumes or smoke, or aspiration of liquids or objects.

Double aortic arch is a relatively rare congenital cardiovascular malformation. DAA is an anomaly of the aortic arch in which two aortic arches form a complete vascular ring that can compress the trachea and/or esophagus. Most commonly there is a larger (dominant) right arch behind and a smaller (hypoplastic) left aortic arch in front of the trachea/esophagus. The two arches join to form the descending aorta which is usually on the left side. In some cases the end of the smaller left aortic arch closes and the vascular tissue becomes a fibrous cord. Although in these cases a complete ring of two patent aortic arches is not present, the term ‘vascular ring’ is the accepted generic term even in these anomalies.

Tracheal intubation, an invasive medical procedure, is the placement of a flexible plastic catheter into the trachea. For millennia, tracheotomy was considered the most reliable method of tracheal intubation. By the late 19th century, advances in the sciences of anatomy and physiology, as well as the beginnings of an appreciation of the germ theory of disease, had reduced the morbidity and mortality of this operation to a more acceptable rate. Also in the late 19th century, advances in endoscopic instrumentation had improved to such a degree that direct laryngoscopy had finally become a viable means to secure the airway by the non-surgical orotracheal route. Nasotracheal intubation was not widely practiced until the early 20th century. The 20th century saw the transformation of the practices of tracheotomy, endoscopy and non-surgical tracheal intubation from rarely employed procedures to essential components of the practices of anesthesia, critical care medicine, emergency medicine, gastroenterology, pulmonology and surgery.

Tracheal agenesis is a rare birth defect with a prevalence of less than 1 in 50,000 in which the trachea fails to develop, resulting in an impaired communication between the larynx and the alveoli of the lungs. Although the defect is normally fatal, occasional cases have been reported of long-term survival following surgical intervention.

Advanced airway management is the subset of airway management that involves advanced training, skill, and invasiveness. It encompasses various techniques performed to create an open or patent airway – a clear path between a patient's lungs and the outside world.

Tracheoinnominate fistula is an abnormal connection (fistula) between the innominate artery and the trachea. A TIF is a rare but life-threatening iatrogenic injury, usually the sequela of a tracheotomy.

Laryngotracheal reconstruction is a surgical procedure that involves expanding or removing parts of the airway to widen a narrowing within it, called laryngotracheal stenosis or subglottic stenosis.